'If I don't recognize the other, there is only a simulation of dialogue, a monologue'

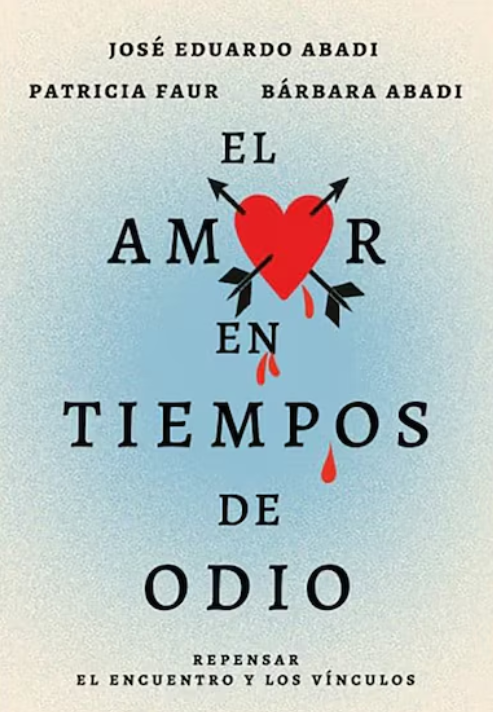

José Eduardo Abadi, an Argentine psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and writer, seems tireless. He has published 12 books, treats patients, and frequently receives consultations from leaders, the media, and business leaders. In October 2024, he published a book written with Patricia Faur and Bárbara Abadi: Love in Times of Hate: Rethinking Encounter and Bonds (Grijalbo).

Love, in all its dimensions and spheres, is under threat: building and strengthening bonds in a climate of intolerance, cruelty, and narcissism—amplified by social media—becomes practically an impossible mission, Abadi believes.

In an interview with La Nación, he also reflects on the success of narcissistic leadership in different parts of the world and on the lack of empathy for the sacrifice and pain of others. "When there is no empathic and compassionate understanding from a society that has understood that the sacrifice required of it is difficult, and yet it must be made, there is indifference. And indifference is a form that comes very close to cruelty," he summarizes.

(Continue reading: Between Books and Roses)

There has always been love, and hate, too. What is unique or specific about this "love in times of hate" you refer to in the title of the book?

Love and hate have existed since the dawn of humanity. I speak of love not only as a loving experience, but also as an attitude of caring and protecting, that is, availability toward the other; basically, registering the other in their difference, and being able to give and receive from that other something that allows us to grow, change, and connect in a enriching way. Now, each sociohistorical period also has its particularities, and the exercise of love and hate has, therefore, had important differences in different eras.

José Eduardo Abadi has published 12 books. Photo: IG: jeabadi

We are now at a time when there is a difficulty in our relationships with one another. In some countries, including Argentina, that record of interest in each other and that love that allows us to build a whole is going through a very delicate moment. I think love is desperately crying out for the need to exist again, I would almost say as an indispensable premise for forming a global project. And when this doesn't exist, those gaps, those cracks, those absences don't remain as a blank, but are instead filled with other things that have to do with distance, aggression, violence, suspicion of the other, and hatred.

Rather than integrating, we seek to defeat the other; the desire to dominate and subjugate the other predominates. Without empathy, there is no compassion; and without understanding the other, there is no civic friendship, which is such a beautiful, necessary, and forgotten concept. The other today is not an interlocutor with whom I seek to learn, nor a recipient to whom I tell what I think, but rather a suspect or an enemy whom I must convince or even subdue. One expression of this is fanaticism.

Why do you think these authoritarian, pathologically narcissistic narratives are strengthened and amplified at certain times?

I think it shouldn't always be for the same reasons. Right now, there's a huge prevalence of narcissism, in a version of society where there's little time to get to know others, where the emphasis has been placed on vertigo; it's disguised by calling it speed, but it's vertigo. That impedes experience.

There's no imprinting of what I've experienced in a way that I can learn from, which is the basic gift we human beings have to improve, work based on love, and not repeat mistakes. For there to be dialogue, there has to be more than one person, and if I don't recognize the other, there's only a simulation of dialogue. There are only monologues. That has nothing to do with conversation, which is something closely linked to love, because it involves listening to others, suddenly registering something that hadn't occurred to me, and even thanking the other person for what they're explaining to me. And this depends on activating an essential ingredient of love: generosity.

There's a characteristic that occurs in some countries: high-ranking officials hurl insults and disparagement at those who think differently. How do you view this phenomenon?

Verbal violence is sometimes a resource that, it seems to me, has different origins. One of them is fear and insecurity. Fear and insecurity lead, as a reactive effect, curiously, to attack. Another variable is that there may be deep-rooted resentment and bitterness. Another problem could be that the other person, in their difference, pierces my narcissism, and I can't tolerate the wound in my narcissistic armor. It also seems to me that insults are sometimes related to mockery. Insults are humiliating, mocking, and anti-love; they are the consecration of bullying. Another variable, also common in people who resort to insults, is related, I would say, to a "rhetorical deficiency." That is, perhaps they don't know how to use language, and so, for these people, insults are a way of saying something more poignantly or incisively, clarifying what they seek to clarify and hitting where they want to hit. It's as if insults were the most sincere and courageous resource.

Perhaps in that gesture people don't see vulgarity, fear, or resentment, but rather authenticity, "he says what he feels."

In October 2024, he published a book co-authored with Patricia Faur and Bárbara Abadi. Photo: .

Of course. If he insults, it's "because he tells you what he feels." Now, one is reminded of phrases from certain politicians and thinkers throughout history that we repeat in admiration and who didn't need the insults. For example, when Cicero looks at Catiline, who intends to become dictator of Rome, and says: "How long, Catiline, will you abuse our patience?" And there's another, more common one, but one that also moves us deeply: when Winston Churchill says:

“We're going to finish this with victory, but for now I can offer nothing but blood, effort, sweat, and tears. We have before us a test of the most painful kind. We have before us many months of struggle and suffering.” It's brutally powerful, incredibly forceful. And it's a phrase that needs no insult.

One thing we've seen in Argentina with the downsizing of the state and public sector layoffs is a certain celebratory mood among some officials over the cuts and savings, without mentioning the pain and impact on families. The writer Martín Kohan referred to a certain "joy in cruelty"...

The distinction between traveling a painful path and celebrating is interesting. Nothing is given on its own; everything is built, and it has to do with making the decision to, together, carry out a transformation that will make us live better. This requires time, patience, and effort, and it's always achieved together. One would have preferred everything to be okay, but if it isn't, I have to work to make it so. That's one thing. Now, to celebrate in terms of not registering the pain of others, of not having compassion, that's another. Celebrating people's sacrifice is a form of cruelty.

When there is no empathetic and compassionate understanding from a society that has understood that the sacrifice required of it is difficult, yet it must make it, there is indifference. And indifference is a form that comes very close to cruelty.

Why do you think narcissistic leaderships that involve a high level of cruelty are so successful?

Narcissism is very present in today's society: we elect leaders onto whom we can project our narcissism, we deposit it there. By electing them, we elect ourselves. Or, by electing them, the leader will enhance those omnipotent fantasies we may have. On the other hand, the narcissistic leader tells you they're going to do things that only they can do, that they're going to achieve what, without them, you could never achieve. They tell you there's paradise in this earthly life, that there's redemption and a promised land, and that you'll access all of this through them. The narcissistic leader tends to slip, not toward authority, but toward authoritarianism. These are leaders who don't believe in learning, in heterogeneity, in a world of conflict, in the recognition that if we don't accept that there is adversity, frustration, pain, and loss, we are denying our human character.

How much magic is there in these leaderships?

There's something magical about this kind of leadership in the sense that there's supposedly someone capable of performing a miracle. It's a force that, unconsciously or consciously, makes me feel protected, and that's why I remain calm. But the illusion generally ends in disappointment, and narcissists, if they remain in power for too long, end up leading dangerous authoritarian regimes. To avoid narcissism and this type of illusory and offensive abuse, that's what democracy is for, that's what the separation of powers is for, that's what limits are for. And in the establishment of individual and relational psychology, there's the superego, moral conscience, respect for others, empathy, companionship in grief, the recognition of the courage to suffer for what hurts and for what one suffers, and the rescue of us from our shadows when something painful happens, so we can once again exercise our vital capacity.

For the Nation (Argentina) - GDA

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fede%2F2a0%2F17e%2Fede2a017e9640422d829dac765cf5513.jpg&w=3840&q=100)