'It's more dangerous to go to conflict zones today than it was 20 or 25 years ago': Jesús Abad

It's just another day at the exhibition "Fin y Principio" by Jesús Abad Colorado, at the El Museo gallery in Bogotá. The documentary photographer arrives for this interview, but the visitors are not lost on him, as he begins to share anecdotes and details from his photos. He welcomes them and asks their permission to attend the event for which he is at El Museo, as if he were guilty of not being able to continue answering the questions stuck in the curious eyes of the people who admire his images.

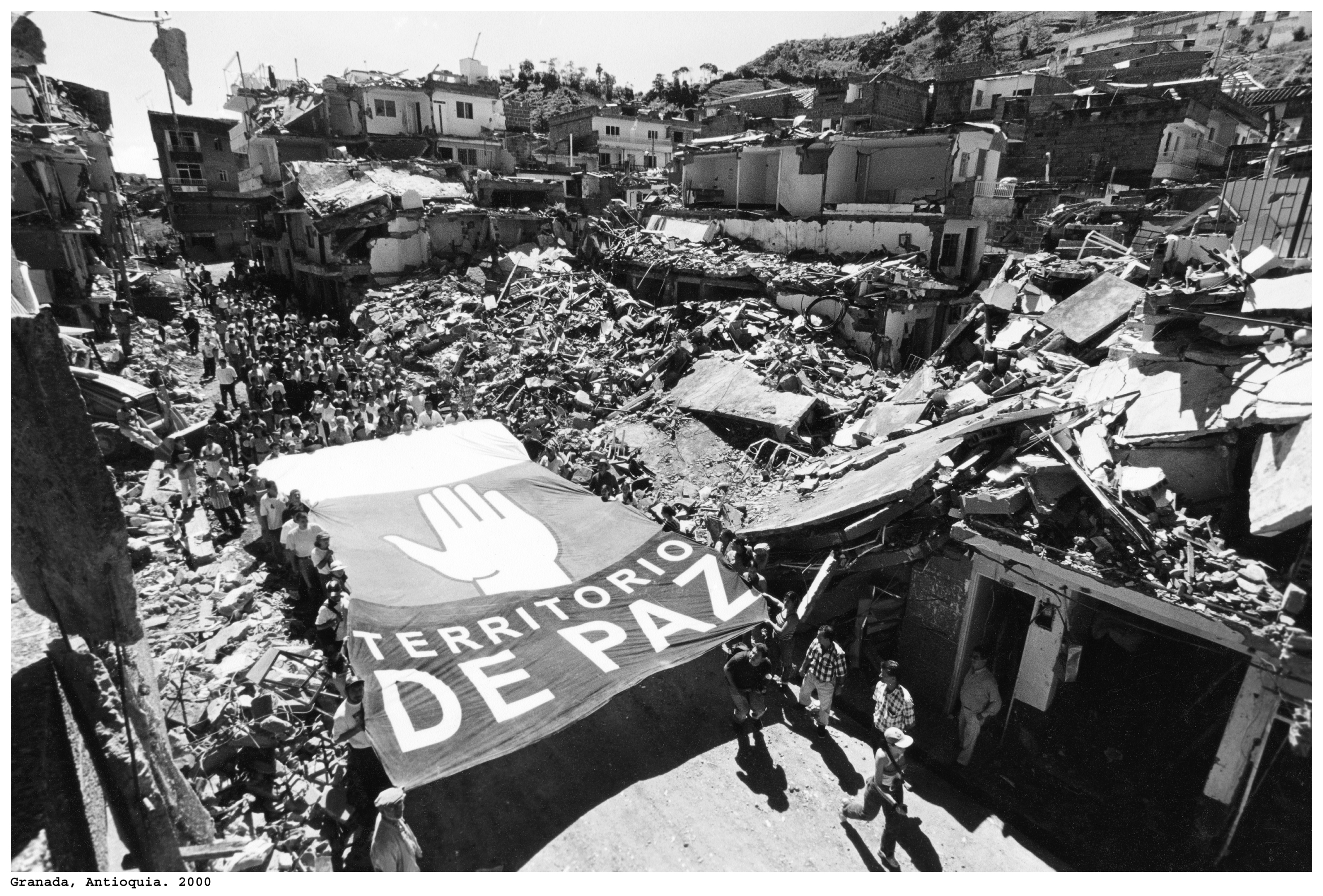

Jesús takes a deep breath, and we begin our tour of his exhibition. It's a conversation between photographers that begins with the six-image black-and-white module on the front wall of the room (opening photo), which is the most striking for visitors because the war hits them in the face and shows how it eventually permeated the country, not only in the countryside but also in the cities.

The first image I'm talking about recalls the famous photographs of the Normandy landings, better known as D-Day, which marked the beginning of the end of World War II. It shows the land, sea, and air invaded by war, in the photographer's words. It is accompanied by five other striking photos: on the left, an Army soldier embraced by four machine gun bullet belts , resembling armor; on the right, paramilitaries guard Commune 13 in Medellín; below, armed men from the now-defunct FARC guerrilla group pose for the photographer's lens; next to it, three police officers with shields observe an eviction in the eastern highlands of Medellín.

Finally, to the right of the module is one of the most recognizable images of Colorado, in which a man wearing a camouflage uniform, rubber boots, and a hood gives instructions to soldiers of the Urban Anti-Terrorist Forces, raising his arm at half-mast and pointing his fingers toward the houses, a gesture that seems like a sentence, in the midst of the remembered Operation Orion. That photo was testimony to the involvement of paramilitaries in that operation, which left more than 600 victims , including dead, wounded, displaced, and missing, according to the National Center for Historical Memory.

Photojournalist Jesús Abad has dedicated 33 years to documenting the Colombian armed conflict. Photo: Andrea Moreno. El Tiempo

In the gallery's main hall, there are a dozen university students visiting the exhibition at the recommendation of their professors, who see it as an opportunity for young people to recognize the conflict in the country, which, from the distance of the city's classrooms, seems distant and black and white . Jesús could very well be one of those teachers. When he sees them, he can't help but ask them where they come from, what they study, who told them to come, and tell them the story of one of the images.

Visiting "End and Beginning" is more of a pilgrimage, a journey to a place very similar to a sanctuary where we encounter the death and pain of the country's victims right in front of us . All these stories have their own names, like that of Luisa, a 9-year-old girl, a survivor of the 2005 San José de Apartadó massacre and a victim of forced displacement, who poses inside a tree; or that of Leidy Lorena, who fled with a chicken in her arms from the massacre in Puerto Alvira, in Mapiripán.

Jesús's intention with his photos is clear: that these faces have an identity in the present and remain in people's memories so that they are not forgotten , so that the victims do not end up being just another number in official reports.

Residents of Granada, Antioquia, march after a guerrilla takeover on December 7, 2000. Photo: Jesús Abad Colorado

What is the common thread of this exhibition?

Here's a series of images that trace my career back to the beginning of my career, in 1992, with the photo of the shooting gallery and the story of Cain and Abel, taken where 14 young men were killed while serving in the military. That was my first exercise, as a photojournalist for El Colombiano, in confronting a war scenario that also involves nature with issues like attacks on oil pipelines and displacement. In the exhibition, I piece together fragments of the country's truths to tell the story from the perspective of the victims, the losers. Hence the name of the exhibition, "End and Beginning," because in January of this year, in Catatumbo, we had more than 50,000 people displaced by the confrontation between the ELN guerrillas and the FARC dissidents. With 33 years of experience, I'd never heard of so many people displaced in one week.

After so many years covering the conflict, what motivates you to continue telling these stories and photographing the war?

In the 1970s, my family had to flee the countryside to the city. My grandparents were among the 300,000 dead in the middle of the last century. No one named them; there's only a short paragraph in El Colombiano, from a news story from August 1960, which says that hooded men entered the house and murdered them. This is the story repeated over endless centuries. In wars, names are always lost; we forget that every peasant had a story, crops, animals, and dreams. I wish this wouldn't happen again. And my work is about naming so we don't forget.

In the exhibition I gather together fragments of the truths that the country has to tell the story from the victims, from the losers.

What are the challenges facing documentary photographers in Colombia today?

The first challenges are those of respect and humanity. A reporter must always look people in the eye. If you say you're going to publish an article to tell a story, hopefully it will be fulfilled; if not, it's better not to promise anything. As reporters and journalists, we face very complicated situations, because today it's more dangerous to go to conflict zones than it was 20 or 25 years ago. There's a proliferation of small dissident groups from different armed groups. The FARC, even if you didn't like them, had a general staff and blocs that were accountable for each of their actions. Today, the dissident groups in Cauca, Nariño, and the entire Pacific basin are interested in enrichment, so they lack an ideological project. They're seeking to supply illegal markets through mining and drug trafficking. For us as journalists in conflict regions, these multiplied dissident groups make our work difficult, because each group is full of commanders, and it's hard to tell who's who.

Amid the quest for immediacy that permeates the world of information and social media, what is your opinion on the coverage of conflicts, not only in Colombia but around the world?

Two years ago, I published more than I do today on X. I'm taking much more care. There are many people interested in becoming influencers and protagonists of history without having walked the country, who lack professional training in journalism, social sciences, or psychology. The exercise of narrating history is not for those of us who studied photography. A camera is very easy to use, and today it's much simpler to publish and tell stories through social media. In the past, we carried film, a darkroom, and chemicals to develop photos in the territories and send them to the cities. We had to put in more effort. Today, with a cell phone, you send a photograph to a newspaper through digital media, and it becomes universal. Amidst this immediacy, people just want to publish, and there's no filter. There are photos that I've delayed publishing for several years.

In the midst of that immediacy, people just want to publish, and there's no filter. There are photos that I've delayed publishing for several years.

How raw does an image have to be to generate reflection or an act of awareness about what is being told?

There is music that is beautiful and there is music that offends. In narrative, there are ways of seeing, of writing. Ethics is not a class for philosophy students. Ethics and aesthetics must always go hand in hand. Images must shock, not make you want to ignore them. I was the first journalist to enter Bojayá; I have photographs of the victims and I saw bodies being removed from that church. What is the image the country knows? That of the mutilated Christ. Whoever sees that photo will understand that's how people were left. What I always seek is to generate reflection, not hatred or a thirst for revenge.

What's your current focus as a documentary filmmaker? Is there any conflict or situation that particularly catches your attention?

If it were up to me, I would dedicate myself only to exploring hopeful themes and seeing the beauty of the country as taught to us by the photographer and teacher Andrés Hurtado, but there are conflicts that are forgotten. What is happening today in the Catatumbo, Cauca, Chocó, and Putumayo regions is very complicated. There is a duty to go and leave a testimony. Right now, I am taking care of myself because I am recovering from surgery due to a fall I suffered in the Yurumanguí River basin (Buenaventura). But I want to talk about hope because I believe we must leave a testimony of all the richness of our country. In the territories, one finds all the beauty and all the love of those who live and try to conserve the forests, of those who plant and send the products so that we can feed ourselves in the cities.

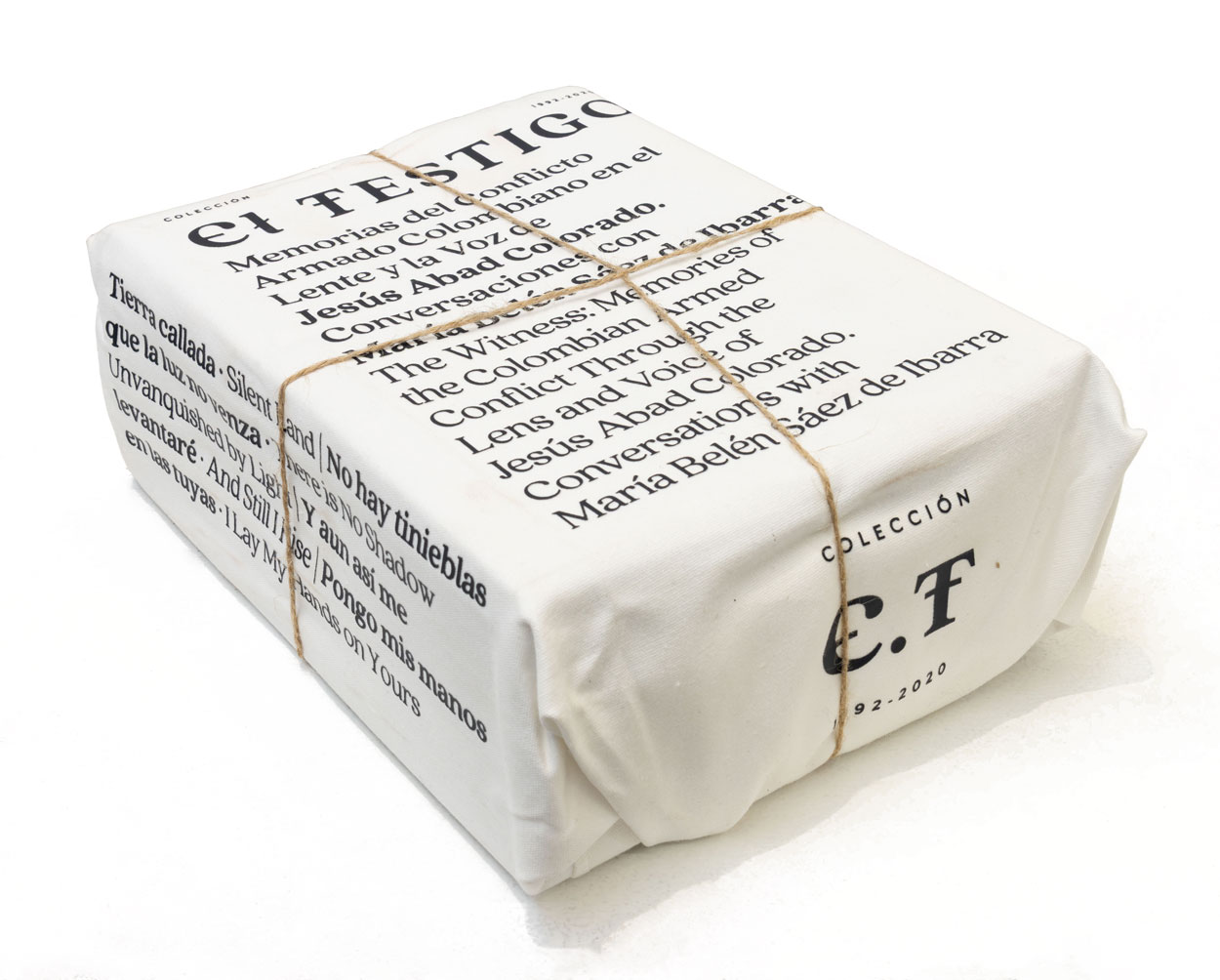

The "The Witness" collection consists of four volumes that bring together 700 of Abad's photographs. Photo: Courtesy of the Museum

Is there any fact you regret not having documented?

There are several I couldn't document due to lack of resources, because my equipment was stolen. Regarding conflict, everything related to the FARC hostage exchanges. I would have liked to tell those stories. Looking back, I would have liked to have been involved in the peace process with the EPL.

What is the active conflict that needs to be covered?

I've been invited several times to document the migration through the Darien jungle. I'm not going because I'm stuck halfway there. My right knee is bothering me, and if I accepted, I know it would give out at some point. The other thing is that I don't like to go and do stories that are very central to the moment. There are other jobs that need to be done for the memory, not for awards.

Instagram: @andreamorenoph

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fede%2F2a0%2F17e%2Fede2a017e9640422d829dac765cf5513.jpg&w=3840&q=100)