Oliver Jeffers, the children's literature bestseller who tells stories to unite the world

Oliver Jeffers's first memory of a book is stained with blood. His own. He says he was four or five years old and his father was reading him the Australian classic Watching Matilda. Suddenly, a red drop fell from the boy's nose, hit hours earlier by a ball, right in the middle of a page. "Oh no, I ruined it," he thought. He still has that volume, complete with damage. He even offers to send a photograph. That was the beginning, in a way, of a path that has led him to the opposite: today Jeffers (Port Hedland, Australia, 48) beautifies everything he touches. Paintings, sculptures, collage. And especially children's albums. His illustrated works have sold more than 18 million copies, in some 50 languages. His debuts , How to Catch a Star , Lost and Found , and We Are Here, already inhabit homes around half the world. Through imagination, sensitivity, humor, and respect for the intelligence of his young fans, Jeffers still saturates the pages, but with his unmistakable style.

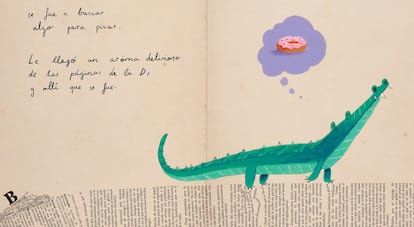

Where to Hide a Star (Andana) offers the most recent example. It also marks the return of some of his most beloved characters: a boy, a penguin, and a star. More generally, the book once again demonstrates the reasons that have placed Jeffers in another realm: that of children's literature. Both his writing and his plots brim with humanity, tenderness, and wonder. A crocodile wanders through a dictionary, several ghosts play hide-and-seek with a girl—and with the reader—a family car takes off into space. The author assures that stories and simplicity are what matter most to him. But, in addition to fantasy and surprise, his books construct a monument to empathy. “It's one of our key characteristics. The most important thing for us is people. And our biggest problem, to me, is disunity, our lack of collective agreement on where to go and how to get there. Capitalism and individualism fuel it,” the author explains by phone. A tool that, by the way, he considers dangerous: he has just joined the Smartphone Free Childhood movement.

His works champion just the opposite: looking at the world, experiencing it, and sharing it. In We Are Here, an endless line of human beings of all kinds come forward to help a baby when its parents are unable to do so. In What We Will Build, A father and a little girl lift a door “where there hadn't been one before.” Jeffers abhors conflict and believes his worldview began to take shape in the turbulent Belfast of the 1970s and 1980s, where he grew up, in the midst of the Northern Irish War. “There came a point where no one knew why they were killing each other anymore. Or why everyone would continue to go against their own interests. They tell you that you're the victim, and everyone tries to save themselves and that the problem is someone else's,” he reflects. Hence, his pencils attempt to draw the path toward a different future: one that his tiny readers can forge. And his own children, to whom Jeffers dedicated two of his works.

“A while ago, I was asked, 'What would you say to a young person who wants to be a climate artist?' I replied: just be an artist. You can't be dictated by an agenda. And children can tell if they're being patronized by moral lessons. Books aren't about propaganda or advertising, they're about stories,” the author notes. At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, to which Jeffers was invited, he happened upon another good synthesis. The girl who registered him noted that the heading “artist” didn't exist. Hence, she placed him in the category of “observer and translator,” a definition the writer embraces today.

Perhaps it serves to summarize a career that oscillates between conceptual art, museum exhibitions in various countries, music videos and covers for the band U2, or collaborations with brands such as Starbucks, Kinder, and Sony PSP. Here We Are in 2020, he made the leap to animation , in a short film narrated by Meryl Streep. “I always knew I wanted to be an artist. But dedicating myself to books happened by accident,” the author recounts. Until college, it seems, he had little interest in them. They seemed like “homework.” Young Jeffers was busy climbing trees, playing soccer, helping take care of his mother, who suffered from multiple sclerosis, or dodging the delinquency of a fellow gang member. He loved painting, and at 15, he sensed it could be his profession. For reading, however, he had neither the time nor the inclination. Until an idea he had refused to stay in a painting. He imagined someone trying to catch a star. How would he do it? Little by little, he conceived several different attempts. Finally, he realized that he, too, had something in his hands: a book.

When he published it, he was asked if he had a second one in the works. He said yes, even though it was a lie. But the truth is, he ended up creating more than twenty. They were overwhelmingly successful: “I try not to think about it, because of the responsibility it entails and because if you reveal a magic formula, it loses its power. When I analyzed it, I found three possible reasons. My first contract was with a British publisher, not an American one, where the market is so large that I wouldn't have been given as much care. Besides, I don't try to talk down to children; I'm genuinely driven by curiosity about the world. And then there are the universal values of the stories.”

The truth is that his books have moved people in very different and distant countries. Although he himself admits that he treads on a slippery slope: the right emotion, always one step away from falling into none, or too much. “It’s the hardest part. You do it again and again and again. You step away from the work, you give it a break, you come back and maybe you realize you’ve gone too far. It’s about finding a balance,” he maintains. Jeffers continues to pour his heart into each book. Fortunately, the blood is gone.

EL PAÍS