Each person has a unique breath as distinctive as fingerprints or voice.

Inhale and exhale: that's your respiratory fingerprint. Every human being has a unique and consistent nasal breathing pattern . So consistent that it's possible to identify a person solely by how they breathe. This is what a new study published Thursday in Current Biology determined. It followed 100 participants—some of them for up to two years—to understand how breathing is unique to each individual. And how, through it, information can be obtained about physical and mental health, from body mass index to anxiety or depression levels.

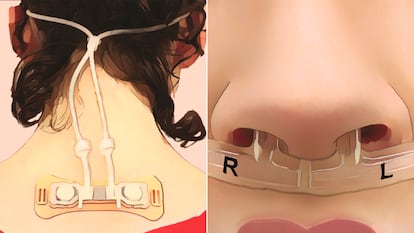

To measure this, the researchers developed a portable device that recorded airflow through each nostril for 24 hours straight. They then collected data on each volunteer's physical activity level and responses to psychological questionnaires. They cross-referenced all this data using artificial intelligence and statistical analysis, and were able to identify 97% of the participants using only their nasal airflow patterns. In other words, breathing is as distinctive to a person as their voice or fingerprints, and most of its characteristics remain unchanged over time.

The respiratory signature is not a passing fad and holds enormous potential for science to try to unravel the mystery of brain function in mammals. Noam Sobel, a researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and co-author of the study, says that “one would think that breathing has already been measured in every sense.” However, his team has discovered a completely new way to analyze it. “We consider it a brain indicator,” he explains.

This is because, as they have been able to demonstrate, breathing—so unnoticed, even though we experience it an average of 12 to 20 times per minute—reflects physiological states and mental traits . Sobel sums it up this way: “Our levels of anxiety and depression are shaped by our brains, and so are our long-term breathing patterns. So, by reading these patterns, we are, in a way, reading the mind through breathing.”

Although none of the participants in the study were clinically diagnosed with a mental disorder, those who scored higher on the psychological assessment tools used to measure its severity exhibited similar breathing patterns. This means that individual psychological traits can be predicted with statistically significant accuracy based on how the individuals studied breathe .

Now, the million-dollar question seems to be whether our breathing is altered because we have anxiety or depression, or whether we have depression and anxiety because our breathing is altered. “In short, we don't have an answer. While both are possible options, the latter alternative is, of course, much more exciting because it opens up avenues for intervention,” the author notes. She adds that they are currently repeating the same trials in populations that are clinically diagnosed in order to obtain more data. “Intuitively, we assume that the degree of depression or anxiety we experience alters our breathing , but it could be the other way around. Perhaps our breathing pattern causes these disorders. If this is true, we could modify breathing to modify these conditions,” Sobel reflects.

Timna Soroka, another of the Weizmann Institute of Science researchers who co-authored the article, points out that one of the study's most interesting results relates to sleep. "The waking mind and the sleeping mind are very different , and, in fact, breathing during waking and sleeping is also very different," she explains. For example, nasal breathing during sleep is highly asymmetrical: most people shift between breathing primarily through one nostril or the other. They also found that participants who scored relatively high on anxiety questionnaires had shorter inhalations and greater variability in the pauses between breaths during sleep. "We don't yet know what the implications of all this are," Soroka adds.

Do you want to add another user to your subscription?

If you continue reading on this device, it will not be possible to read it on the other device.

ArrowIf you want to share your account, upgrade to Premium, so you can add another user. Each user will log in with their own email address, allowing you to personalize your experience with EL PAÍS.

Do you have a business subscription? Click here to purchase more accounts.

If you don't know who's using your account, we recommend changing your password here.

If you decide to continue sharing your account, this message will be displayed indefinitely on your device and the device of the other person using your account, affecting your reading experience. You can view the terms and conditions of the digital subscription here.

From Montevideo, Uruguay. She is a journalist for Materia, the Science section of EL PAÍS. She previously wrote for El Observador and presented news for Telemundo. She earned a Master's in Journalism from UAM-EL PAÍS in Madrid.

EL PAÍS