Student creates prosthesis for girl born without a leg: it's made in one day and adapts to any terrain

At the age of five, María Fernanda received her first prosthesis: a homemade mold made from door filler by her father. At that time, the healthcare system had been promising her for years a solution that "was delivered by boat" and never arrived.

Today, nine years later, María Fernanda (Mafe to those closest to her) walks with a 3D-printed prosthesis, light as a feather, strong as her mother, and designed with cutting-edge technology by a young biomedical engineering student who decided to turn his thesis into something more than an academic text.

The case of María Fernanda and her new prosthesis is a story of science, but above all, of humanity. A testimony where knowledge didn't remain in laboratories, where solidarity wasn't exhausted in speeches.

Maria is proof that walking can be a miracle, a right, and, thanks to engineering, also an act of dignity.

Milena Patricia Roa remembers every detail of the day María Fernanda was born. She had a difficult pregnancy: three bleeding bouts, constant hospitalizations , and a health insurance company that barely performed an ultrasound during the nine months.

"I was a member, but they never treated me properly. I burst my water, and a doctor, chatting on her cell phone, told me it was just me needing to go to the bathroom," she says.

María was born without her right leg. Her mother didn't know. No one told her. No one detected it. Nor did they explain why. Milena only remembers crying, confusion, and a huge emptiness. Since then, she has faced alone a path filled with closed doors, medical excuses, and institutional neglect.

Pictured: Milena Roa and María Fernanda. Photo: Courtesy of the School of Engineering.

But also of resistance: “I invented the shoe for my daughter. I stuffed cotton, socks, whatever, into it so she could walk. And she walked. At a year and a half, without a prosthesis.”

Hope arrived when the girl was five years old. Milena and María discovered, by chance, the Fuente de Esperanza Foundation (Fundafe). Milena says she was crying on a staircase, crying out to God for another door that was closing. Fifteen minutes later, her phone rang. It was Juan Ricardo Salcedo, the mechanic who heads Fundafe.

Salcedo asked for a photo of her daughter's stump. The next day, they had an appointment. A week later, María Fernanda had a real prosthesis.

Juan Ricardo didn't study orthopedics, nor medicine. He's an industrial mechanic and the founder of Fundafe, an organization that, for 18 years, has transformed recyclable materials into functional prosthetics for people with limited resources. He does it with determination, creativity, and trust in God.

Currently, thanks to the foundation's visibility, she has a workshop-cart called "Mobilizing Hearts," which she uses to travel the country helping people who lack access to prosthetics.

“At first, I made prostheses with steel and hard aluminum. Making seven prostheses a year made me feel like a grown-up. Today, we make more than 80 annually and perform more than 450 maintenance sessions,” Ricardo explains. All this through a circular economy model that involves communities, businesses, and the willingness of anyone who wants to help.

Juan was also the bridge that brought María Fernanda closer to professors Luis Eduardo Rodríguez Cheu, Jenny Castiblanco, and student Sergio Triviño Ortega, from the Julio Mario Garavito School of Engineering in Bogotá.

In this sense, the rector of the School of Engineering, Myriam Astrid Angarita Gómez, asserts that being able to establish these strategic alliances and, in a way, change María Fernanda's life means "giving meaning to knowledge and meaning to science."

María's prosthesis costs between 25 and 35 million pesos on the market. "We make it for 7 million, because everyone contributes a little bit," says Gómez.

Juan Ricardo, speaking with this newspaper, refers to the alliance between the School of Engineering, Fundafe, and the company 3D Solutions, who, thanks to their joint work, have opened up an opportunity for low-income people in the country who need a prosthesis.

Part of the interdisciplinary team that collaborated to deliver the prosthesis to María Fernanda. Photo: Courtesy of the School of Engineering.

Sergio Triviño Ortega is 23 years old and has a nervous smile that escapes him when he talks about María Fernanda. As a student in the Biomedical Engineering program, part of a partnership between the Colombian School of Engineering and the University of Rosario, he decided that his thesis wouldn't be a forgotten document in a library.

"I wanted something with a social impact. When I met Juan and learned about Mafe, I didn't hesitate: I'd take her on," the young man recalls.

Since then, he set out to design a transtibial prosthesis that was lightweight, durable, functional, and affordable. With the help of his thesis advisors, he also contacted the Colombian company 3D Solutions , which offered him its printers and materials.

They chose a hyperelastic composite called Onyx, reinforced with carbon fiber and stainless steel . The result: a modular prosthesis that adapts to different terrains, can be used on either foot, allows for replacing only the damaged part without remaking the entire foot, and is manufactured in less than 24 hours.

María Fernanda holds her new 3D-printed prosthesis. Photo: Courtesy of the School of Engineering.

"The cost was reduced by 10 to 20 times compared to a conventional prosthesis. And the wait time went from more than a year to less than a week," Sergio explains.

But what excites him most isn't the numbers. "Meeting Mafe changed everything. She wasn't just a grade anymore, she was a life. A girl who wanted to run, play, and dance at 15. I couldn't let her down."

The process of creating the prosthesis combined cutting-edge technology with a deep sense of caring. The result was a happy little girl who could run and dance.

To help María Fernanda achieve maximum mobility, a system of infrared cameras and sensors in the university's gait analysis laboratory measures how a person walks, where they carry their weight, and how their body responds. This information allowed the prosthesis to be calibrated with millimeter precision.

The final assembly took place during a marathon six-hour workday . Sergio, Juan, and the university team worked side by side, measuring, polishing, and adjusting. “We wanted Mafe to feel like she was walking on clouds,” the professors say.

And so it was, one of Maria's first reactions upon trying out her new prosthesis was to be surprised by how light it was compared to the one she already had.

María Fernanda's previous prosthesis was provided by Fundafe. She recalls, "I had a baby giraffe, and they gave it to me in a giant tent, like a stadium."

Today, with her new 3D prosthesis, the feeling is even more liberating. María dreams of playing soccer, jumping, running, and, above all, showing the people who bullied her that she can do it.

“They tell me I can't. But it doesn't hurt anymore. Now I say: yes, I can. I can,” she repeats, like a mantra . Her mother looks at her proudly and says: “I've never limited her. I let her climb hills, jump. Because children shouldn't be limited, they should be accompanied.”

The impact that is just beginning The prosthesis's design will not remain a secret. Sergio and his team decided to release it as open source. Anyone in the world will be able to download, print, and adapt it to their needs.

“We want no one else to have to wait years or risk their lives for a prosthesis,” says Professor Rodríguez Cheu.

Sergio and his mentors' vision is ambitious: to create a global network of open access to low-cost, high-functionality assistive devices.

A world where walking is not a privilege, but a right guaranteed by science, solidarity, and the will of those who can contribute.

Rector Astrid Angarita calls for partnerships between higher education institutions, private companies, and the government to generate new innovative solutions that, with their social focus, help more people.

This project doesn't end with María Fernanda. Fundafe, the universities, and 3D Solutions are already considering new collaborations.

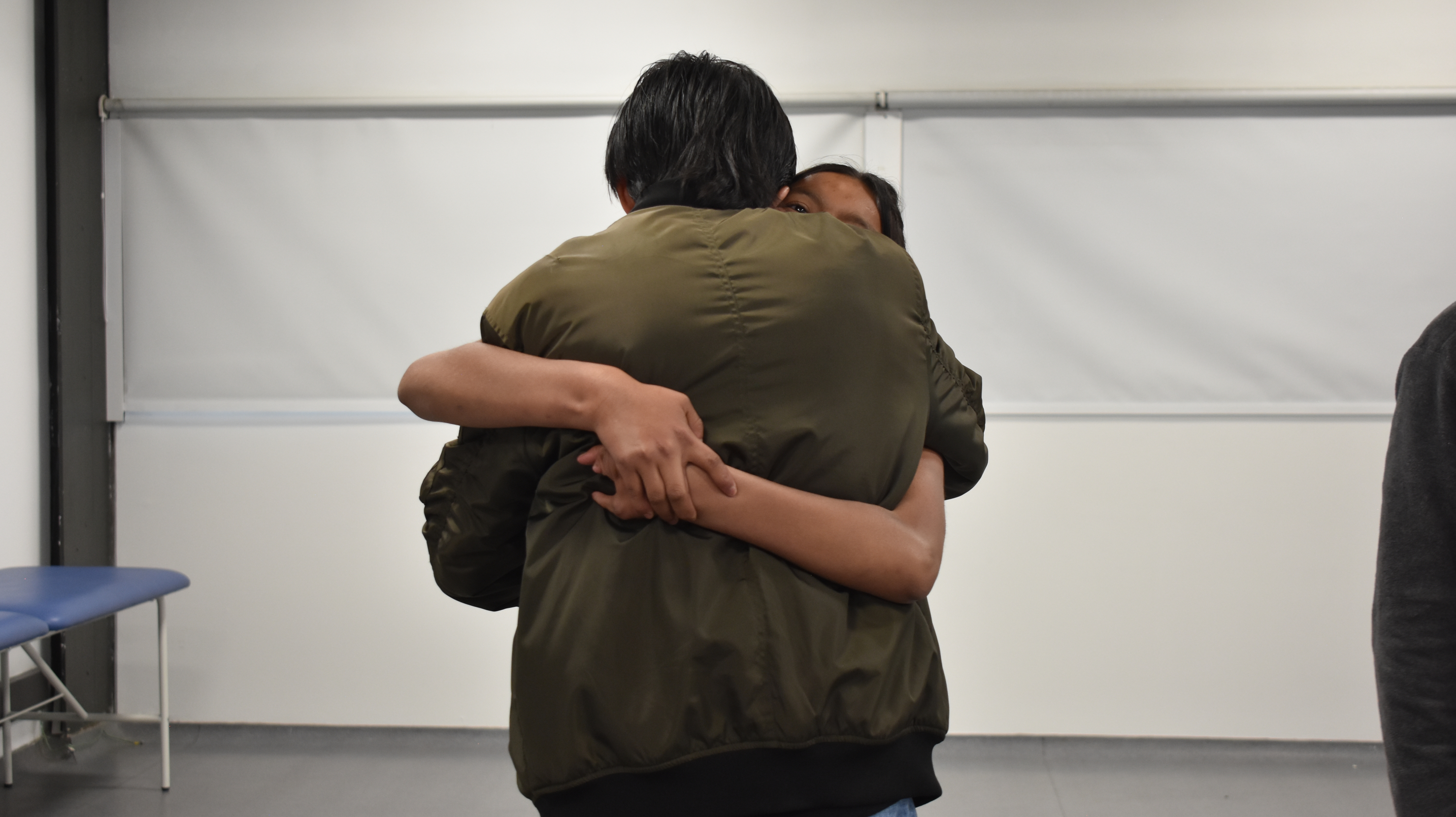

María Fernanda's grateful hug to student Sergio, who created her prosthesis. Photo: Courtesy of the School of Engineering.

The technology developed is not only useful for prosthetics, but also for surgical guides, cranial implants, and other medical solutions. Furthermore, the data collected will inform future scientific research and academic publications.

"We want to build evidence so that the health system understands that this is viable, necessary, and urgent," says Professor Jenny Castiblanco.

Because, as Juan Ricardo concludes, "foundations shouldn't exist. This is the responsibility of the State. But while that happens, here we are. Walking with the scrap, transforming lives."

The day María Fernanda tried out her new prosthesis, she ran without stopping. Sergio watched her with tearful eyes. Juan smiled like a proud father. Milena hugged her daughter tightly. That day, Colombia, without realizing it, took a leap toward a more just future.

Because with María Fernanda's hope for a better quality of life and being able to fulfill her dream of playing soccer, there is also good news for the country and the people who need it most.

ANGELA MARÍA PÁEZ RODRÍGUEZ - SCHOOL OF MULTIMEDIA JOURNALISM EL TIEMPO.

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F9f3%2Fafb%2Fdae%2F9f3afbdae93501f253333ee3da42efed.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F299%2F1c9%2Fa76%2F2991c9a76bc92eceaaa568fa9c3303ed.jpg&w=3840&q=100)