Frontex illegally transferred data on migrants and activists to Europol for years.

Under the banner of combating human trafficking, the European border surveillance agency, Frontex, collected personal data for years through covert interrogations of migrants upon their arrival in Europe, lacking basic legal safeguards. Between 2016 and 2023, the agency illegally transferred the data of more than 13,000 people to Europol, the EU law enforcement agency. There, the data was stored in criminal intelligence files for use in member state police investigations. An investigation by Le Monde, Solomon , and EL PAÍS—based on hundreds of pages of internal documents and interviews with data protection experts and lawyers—reveals Frontex and Europol's involvement in opaque and legally questionable practices that lead to the criminalization of migrants and EU activists who assist them or have been in contact with them. The border agency was forced to change its data transfer protocols following a report by an independent EU body that deemed this practice unlawful.

“My whole life was in that police file: my relatives, my calls to my mother, even false details about my sex life. They wanted to portray me as promiscuous, a lesbian, using morality to make me look suspicious,” says Helena Maleno, 54, a Spanish human rights defender who was targeted by law enforcement for her work informing authorities about people in danger trying to reach Europe by sea. It was criminal investigations, launched more than a decade ago by authorities in Spain and Morocco, that exposed the extent of the police siege around her.

The file on Maleno compiled by the Spanish National Police included, among other things, three Frontex documents containing details of interviews conducted by European agents with migrants who had arrived by boat in Spain between 2015 and 2016. The reports, which this investigation has accessed, contained information, including her Facebook account, that presented her as a suspect in human trafficking. The Spanish police had obtained these reports from Europol's criminal database in late 2016.

For years, human rights defenders have warned about attempts to criminalize irregular migrants and EU citizens who provide assistance at European borders, often on shaky legal grounds. Hundreds of migrants or human rights activists are arrested each year on charges of facilitating irregular migration.

Helena Maleno wasn't the only one to face this problem. Norwegian Tommy Olsen and Austrian Natalie Gruber, both well-known activists, found their personal data also included in Europol's criminal information database.

On the hunt for informationThe first suspicions about Frontex and Europol exchanges date back to June 2022, when the EU's European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), an independent authority, issued negative opinions on Frontex's rules regarding data processing and launched an investigation.

It did so after analyzing the so-called debriefing interviews that Frontex officers conduct with national authorities with migrants upon arrival on European shores, which are, in theory, voluntary. During these interviews, they are asked questions about the reason for their trip, the journey, or the possible modus operandi of human trafficking networks. The EDPS report questioned the voluntary nature of these interviews, citing that "due to the vulnerable position of the interviewees and the way they phrase the questions, their voluntary nature cannot always be guaranteed." Fran Morenilla, a lawyer specializing in migrant assistance, agrees: "There is no record of them anywhere because there is no signed consent form."

Second, the EDPS inquired about the use of the information collected. Unlike Europol, Frontex has no legal mandate to investigate crimes or to collect personal data to identify criminal suspects. The EDPS criticized Frontex for routinely labeling anyone mentioned during a debriefing as "suspects" and "forwarding" this information to Europol, including "data on persons the interviewee has heard of or seen, but has not been able to verify the credibility of the name given, or if the name is mentioned out of fear or in an attempt to gain some benefit."

Under Frontex's current mandate, in force since 2019, the agency is only authorized to share this data with Europol on a strictly case-by-case basis.

Following the EDPS's investigations, an email sent last December by Nayra Pérez, then head of the Frontex Data Protection Office, to Executive Director Hans Leijtens and his deputy, Uku Särekanno, summarized a clear verdict: “The EDPS has concluded that the Agency unlawfully transmitted operational personal data to Europol for four years,” Pérez wrote. Indeed, the final investigation report, which focused on data transmissions between 2019 and mid-2023, confirmed that Frontex “automatically” sent each and every report to its colleagues based in The Hague. Already in 2015, in a previous report, the agency warned that Frontex’s automatic transfers “could constitute a potential breach of the Regulation.”

Frontex suspended this practice just four days after the EDPS's preliminary report in May 2023, which included a warning. It has since revised its protocols: personal data is now only shared with Europol in response to "specific and justified" requests. Of the 18 submitted by May 2025, Frontex approved only four. "The agency has drawn clear lessons from this experience," Frontex spokesperson Chris Borowski told this inquiry.

Europol is reticent about whether it will delete data sent illegally, as required by EU law. Its spokesperson, Jan Op Gen Oorth, maintains that the fact that the EDPS has reprimanded Frontex "does not mean that Europol's data processing was not compliant." Niovi Vavoula, a data protection expert at the University of Luxembourg, on the other hand, emphasizes that the ban on automated transfers is a first step, but "Europol's responsibility to delete the data it received illegally cannot be overlooked."

A copy of the EDPS's final report (dated December 2024) obtained for this investigation reveals the scale of the data transfers. Between 2020 and 2022, according to Frontex reports, Europol processed the personal data of 937 individuals considered suspects and issued 875 “intelligence reports,” intended for the respective national law enforcement authorities investigating smuggling . But this is only a small fraction of the reports on more than 13,000 individuals—with names, phone numbers, and Facebook accounts, among other information collected—that the border agency sent to Europol's Migrant Smuggling Centre between 2016 and 2023. Maleno was among them. And Olsen and Gruber suspect they were too.

Turning people into “suspects”Frontex does not collect personal data from interviewees and presents the debriefings of those who share information as entirely voluntary, but reports from the EDPS and legal experts suggest otherwise.

Legal experts argue that interviewees lack legal safeguards, such as the presence of a lawyer, because authorities insist they are not necessary since the migrants are not detained. Daniel Arencibia, a lawyer who works on cases involving migrants accused of smuggling in the Canary Islands, says that what Frontex does during these interviews "takes place in a black box, in the absence of regular criminal proceedings or legal safeguards that could limit the exposure of vulnerable migrants to criminalization."

| DATE | EVENT |

|---|---|

| January 2016 | Automatic data transfers between Frontex and Europol begin |

| November 2016 | Europol sends Frontex reports on Helena Maleno to the Spanish police. |

| October 2022 | The EDPS conducts an audit of data transfers at Frontex headquarters. |

| November 2022 | Hearing on Frontex-Europol transfers in the European Parliament |

| May 24, 2023 | The EDPS communicates the results of the investigation to Frontex |

| May 29, 2023 | Frontex suspends automatic data transfers to Europol |

| November 2023 | Frontex resumes case-by-case data transfers to Europol |

| January 8, 2025 | The EDPS publicly reprimands Frontex for illegal data transfers. |

| January 21, 2025 | Frontex notifies Europol of illegal data transfers |

Gabriella Sánchez, a Georgetown University scholar and former criminal investigator specializing in migrant smuggling, argues that the notion of smuggling used by Frontex and Europol assumes that all facilitators are organized into networks and is based on racist notions about smugglers. But in fact, migrants are systematically accused of facilitating their own smuggling, which accelerates their criminalization. In other words, thousands of people in the EU are caught in the web of data collection.

One person who didn't know that both Frontex and Europol have information on him is Tommy Olsen, a 52-year-old Norwegian kindergarten teacher. He has been alerting authorities for years when people undertaking the dangerous journey from Turkey to Greece are in danger and documenting violent pushbacks by the Greek coast guard. Since 2019, he has faced multiple criminal investigations in Greece, accused of involvement in migrant smuggling, charges he denies.

Freedom of Information (FOI) requests submitted to Europol for this investigation reveal that the agency has at least three "intelligence notifications" that mention the Aegean Boat Report, Olsen's one-man organization. Europol has refused to disclose the contents, which it considers "highly sensitive" and "relevant to past and ongoing investigations." In May 2024, a Greek prosecutor on the island of Kos issued a new arrest warrant for the Norwegian. Although seven previous police investigations against him have already been closed, he now faces a 20-year prison sentence.

“I had no idea Europol had files on me. Why are they collecting and sharing data about my activities and my organization, which is simply trying to defend refugee rights?” Olsen asks.

With more than 800 debriefing officers deployed in its operations in 2024, these interviews constitute, according to the EDPS, Frontex's "largest operational collection of personal data." "It is extremely difficult to analyze exactly how Frontex exchanges data with other actors, because lawyers are kept in the dark," Arencibia emphasizes.

Olsen isn't the only one affected. In May 2022, 35-year-old Austrian activist Natalie Gruber learned of a Europol case against her after submitting a data access request. A co-founder of Josoor, an NGO that documents pushbacks from Bulgaria and Greece to Turkey , Gruber became a suspect after the Greek Prosecutor's Office filed multiple charges, including facilitating the illegal entry of migrants. One of the open cases was dismissed last year, but the second remains open.

Europol has refused to release Olsen's and Gruber's reports for confidentiality reasons, claiming that doing so could "jeopardize criminal investigations." Gruber has challenged this refusal to the EDPS, but her complaint remains unresolved as of 2022. "You're faced with this Goliath of bureaucracy that never tells you anything. All you can do is submit another request and wait. It's exhausting and profoundly affects your life," the Austrian complains.

It remains unclear how Europol obtained the information on Gruber and Olsen, and whether it contributed to the criminal case against them. The request for Olsen's data, submitted to Europol in April, is pending.

Profound consequencesThe cases of Maleno, Olsen, and Gruber represent just a fraction of the thousands of individuals and hundreds of organizations, including humanitarian NGOs, that have landed in Europol databases since Frontex began uploading information to the PeDRA (Personal Data Processing for Risk Analysis) program in 2016, despite prior warnings from the EDPS.

The EDPS warns of the "profound consequences" for those involved; they run the risk of being unfairly linked to criminal activity across the EU, with all the potential harm to their personal and family lives that this entails.

A problem that persistsIn January of this year, Leijtens formally notified Europol that the information transfers made by his agency until 2023 were unlawful. According to EDPS head Wojciech Wiewiórowski, this notification obliges Europol to "assess which personal data are affected by the transfer and proceed with its deletion or restriction."

Although Frontex was forced to change its protocols, in March 2025, its Fundamental Rights Office (FRO) alerted the agency's Management Board to cases in which information from debriefings "was used for the criminal investigation of the interviewed migrant and others." It also expressed concern "about the access to and collection of information recorded on migrants' phones during interviews."

Although Frontex has not yet fully implemented all of the EDPS's recommendations, its human rights monitors now have access to some of the interrogations, and last year Leijtens adopted new, though non-binding, operating procedures designed to strengthen safeguards.

But the premise underlying these data collection efforts is flawed, argues academic Gabriella Sánchez: “EU agencies often justify collecting data on migrants by claiming it is necessary to combat transnational trafficking networks. This creates the illusion that the data is actually reliable or useful. We know that is not the case.”

In 2017, a year after Spain opened a criminal case against Maleno, the Prosecutor's Office closed the case after finding no criminal wrongdoing. However, the case was passed without due process to the Moroccan authorities, who accused her of human trafficking . When she was summoned to testify before the Tangier court that same year, Maleno was stunned to hear the judge refer directly to the Frontex reports: "I was completely baffled. The judge was specifically asking me about the information contained in the Spanish police and Frontex documents. It was surreal, but I paid a high price." In 2019, she was acquitted of all charges .

But the questions remain. “How is it possible that Frontex interrogated migrants about me?” Maleno asks. “Is it really their job to spy on human rights activists?”

In November 2022, the European Parliament's Civil Liberties Committee held its first hearing on PeDRA, the little-known Frontex surveillance program that transfers personal data to Europol.

Frontex Deputy Executive Director Uku Särekanno explained to the MPs that, to date, Frontex had shared data on some 13,000 “potential suspects” with Europol. Särekanno appeared at the hearing alongside two other senior officials closely involved in overseeing PeDRA: Jürgen Ebner, Deputy Director of Europol, and Mathias Oel, then a senior official in the European Commission's Migration and Home Affairs Department.

In synchronized statements, the three officials asserted that the data transfers were exceptional and governed by a solid legal framework.

Särekanno told the Commission: “It’s not a mass transfer of data, but a case-by-case assessment.” “We don’t receive data in bulk from Frontex; it’s done on a case-by-case basis,” echoed Europol’s Ebner. Transfers of personal data occur only on an ad hoc basis ; PeDRA “is not a systematic exchange of data,” said Oel.

This investigation has revealed, in internal correspondence obtained through a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, that the three agencies had previously coordinated to "align" their messages to MEPs. When asked about this, Frontex spokesperson Chris Borowksi stated that Sarekano's statement "was made in good faith and based on the internal understanding and framework in place at the time." Oel claimed that "the statement was based on information provided by Frontex," and Ebner did not respond.

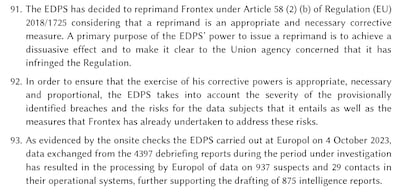

EL PAÍS