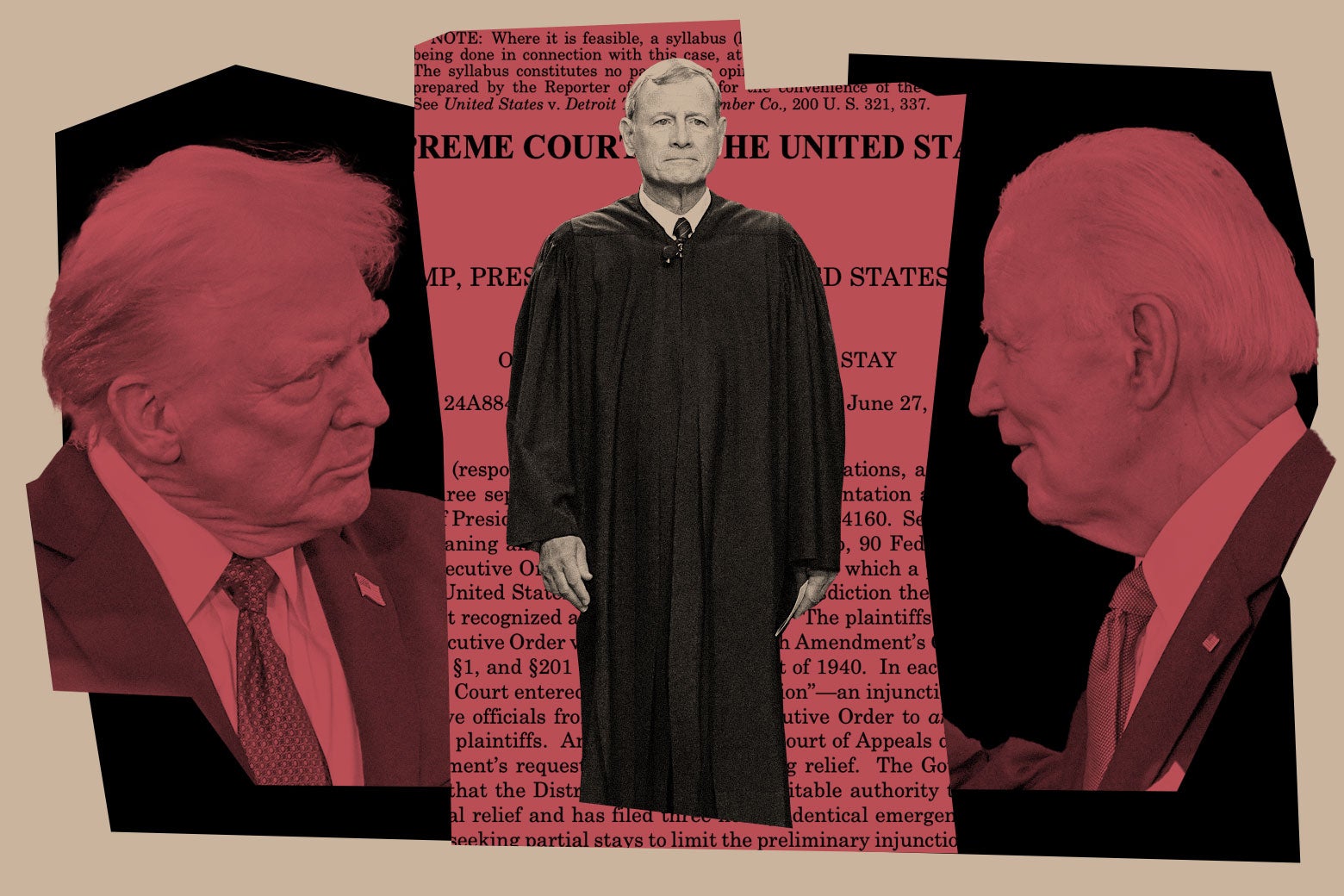

The Supreme Court's Super-Neutral Principle That Applies Only to Democratic Presidents

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">This week's Slate Plus bonus episode of Amicus is a mailbag special in which co-hosts Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern answer listeners' burning questions about the law under the joint reign of Donald Trump's monarchical presidency and our imperial Supreme Court. Amicus listeners have a lot of smart questions, so we're continuing our occasional “Dear (Juris)Prudence” series, in which we share your questions, as well as Dahlia's and Mark's answers. Write to [email protected] to ask a question to Dahlia and Mark. The following transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Dear (Juris)Prudence,

Can you explain why the major-questions doctrine wasn't invoked when deciding the Trump v. CASA birthright citizenship case but was used in overturning student loan relief under President Joe Biden?

Is it because the justices didn't decide the merits of CASA but did decide the merits of student loan relief? And if so, why can the court apparently then choose to decide procedure rather than merits?

—Paul Michael Davis

Mark Joseph Stern: I'll start with the procedural question vs. the merits. That is totally at the Supreme Court's discretion. The court could have asked the parties in Trump v. CASA to talk about birthright citizenship and tee up a ruling on Trump's executive order because it obviously violates the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment. And it shouldn't have been difficult for the court to say so. But instead, it manipulated the docket, manipulated the case, to make it an attack on the universal injunctions that had been holding this executive order back from being implemented, and ignored the merits altogether .

The converse happened in the student loan case . That was really a case about standing, because no one was clearly injured by the Biden administration's student loan forgiveness. The Supreme Court, as Justice Elena Kagan wrote persuasively in her dissent, should have started and ended by saying that nobody had standing in that case. Instead, the court manipulated its standing doctrine to pretend that there was standing by some party, and then the court swiftly reached the merits and invoked the so-called major-questions doctrine, saying that the policy was unlawful. In doing so, Kagan expressly said, the majority violated the Constitution by exceeding its power—a pretty rare charge for a justice to levy at the majority.

So that choice—whether to decide a procedural issue or reach for the merits—is all totally discretionary. But we should always pay attention to how the court is tweaking its docket and the questions that it takes up to reach the outcome that it wants to.

The first part of your question was about the major-questions doctrine , however. Dahlia and I always put this “doctrine” in air quotes . It's not a real thing. It's totally malleable. It's total BS, resting on what five or six justices see as a major question, and when they think they've spotted a major question, then they apply super close scrutiny to what the executive branch has tried to do, and will usually strike it down.

They did this with the student loan relief program under Biden. They did it with climate regulations under Biden. I doubt that they will do this to anything that Donald Trump tries to enact.

I still think it's likely they'll strike down the birthright citizenship order on the merits, though I'm less certain of that than I was a couple of weeks ago. I still think it's more likely than not, but I doubt they'll invoke the major-questions doctrine. I think that that doctrine will lie dormant throughout four years of Trump, and if you had any doubt about that, I'll note that Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a competition at the end of June in which he strongly implied that the major-questions doctrine wouldn't apply to Trump's tariffs. Remember, one of the grounds that the lower court used to strike down the tariffs was essentially invoking the major-questions doctrine to say that Congress hadn't given Trump this power clearly enough. So it was a major question about a power that Trump couldn't exercise, and here is Kavanaugh, one of the key creators of the doctrine, who wielded it so ferociously under Biden, giving up in advance and strongly suggesting that his pet doctrine just doesn't apply to tariffs, because that's foreign trade and that's beyond the remit of the federal judiciary.

This is why I fundamentally object to this doctrine in the first place. It is so malleable that all it really does is help courts pick the outcome that they want to reach, then guide themselves along the way, acting as though they have an actual legal basis for doing so.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.