Factory work is overrated: These are the jobs of the future

Trumpists are unanimous: America needs factories. The president says workers have “watched in anguish as foreign rulers have stolen our jobs, foreign crooks have looted our factories, and foreign scavengers have destroyed our beautiful American dream.” Peter Navarro, his trade adviser, claims that tariffs will “fill every factory half empty.” Howard Lutnick, Secretary of Commerce, offers the most cartoonish argument of all: “An army of millions and millions of human beings putting little screws together to make iPhones—things like that are going to happen in America.”

For years, politicians and some economists have linked the long decline of manufacturing to stagnant wages, the hollowing out of cities, and even the opioid crisis. In the 2000s alone, the United States lost nearly six million factory jobs. Those jobs used to offer young high school dropouts a path to stable and quietly prosperous lives. They sustained entire cities, earning Pittsburgh the nickname Steel City and Akron the Rubber Capital of the World. It's no wonder, then, that politicians across the spectrum are eager to bring those jobs back.

In fact, President Joe Biden shared the same dream as his successor, although he hoped to achieve it through other means. “Where the hell is it written,” he asked, “that we're not going to be the manufacturing capital of the world again?”

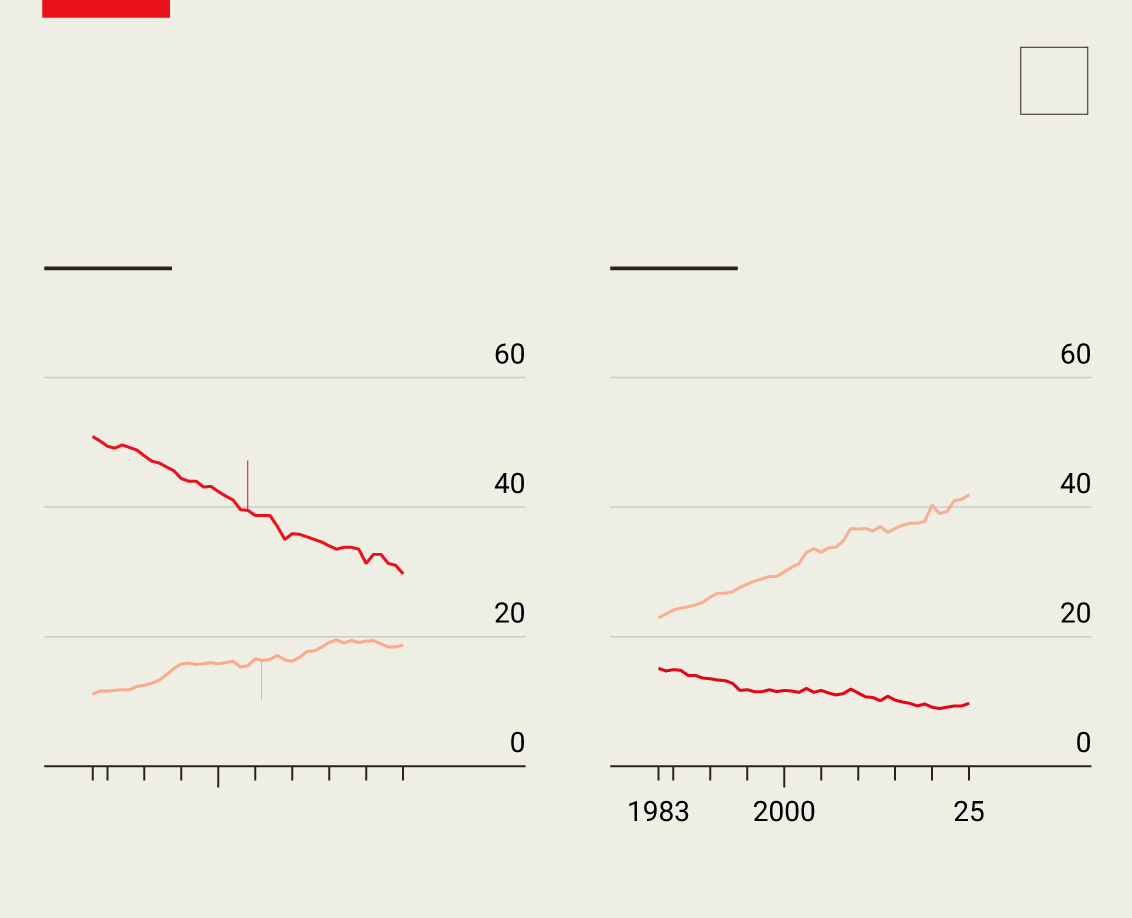

Jobs for the boys

Workers

qualified

e.g. electricians, carpenters

Repair

and maintenance

e.g., air conditioning, general repairs

Security

and emergency

e.g., police, firefighters

Vehicles

and equipment

e.g., mechanics

Operators

and extraction

e.g., drill operators, crane operators

* Bureau of Labor Statistics occupational groups † Median hourly

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

Jobs for the boys

Workers

qualified

e.g. electricians, carpenters

Repair

and maintenance

e.g., air conditioning, general repairs

Security

and emergency

e.g., police, firefighters

Vehicles

and equipment

e.g., mechanics

Operators

and extraction

e.g., drill operators, crane operators

* Bureau of Labor Statistics occupational groups † Median hourly

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

Jobs for the boys

Skilled workers

e.g. electricians, carpenters

Repair and maintenance

e.g., air conditioning, general repairs

Safety and emergency

e.g., police, firefighters

Vehicles and equipment

e.g., mechanics

Operators and extraction

e.g., drill operators, crane operators

* Bureau of Labor Statistics occupational groups † Median hourly

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

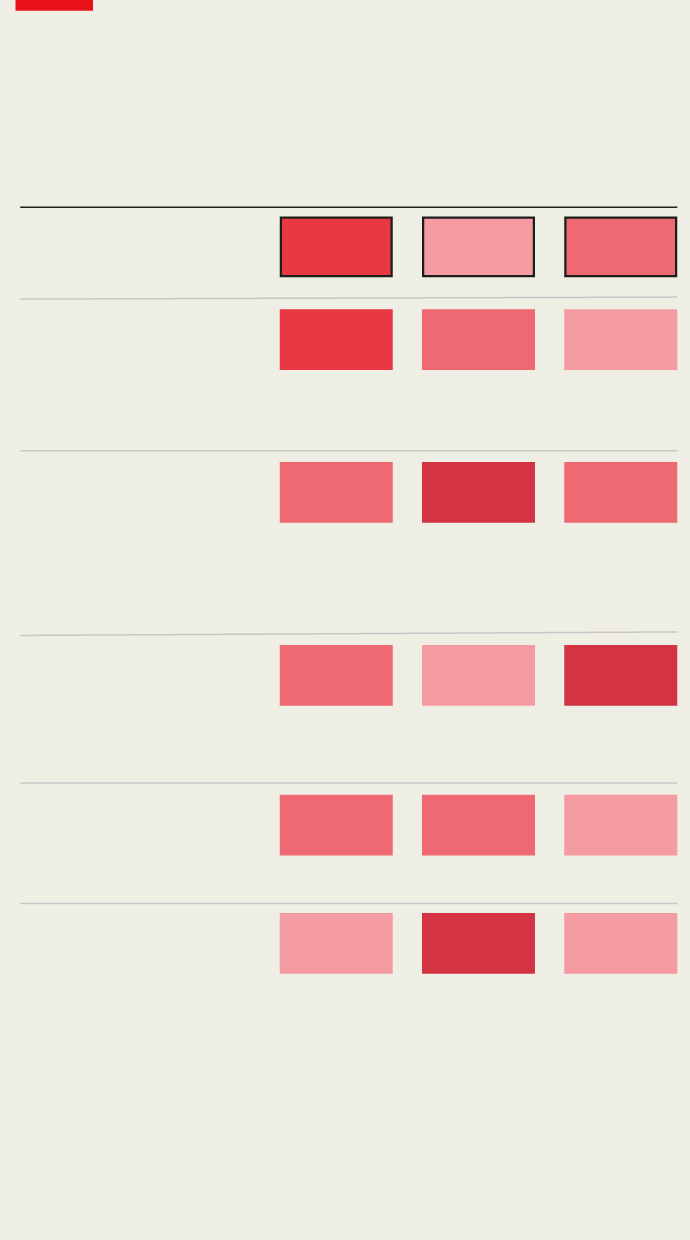

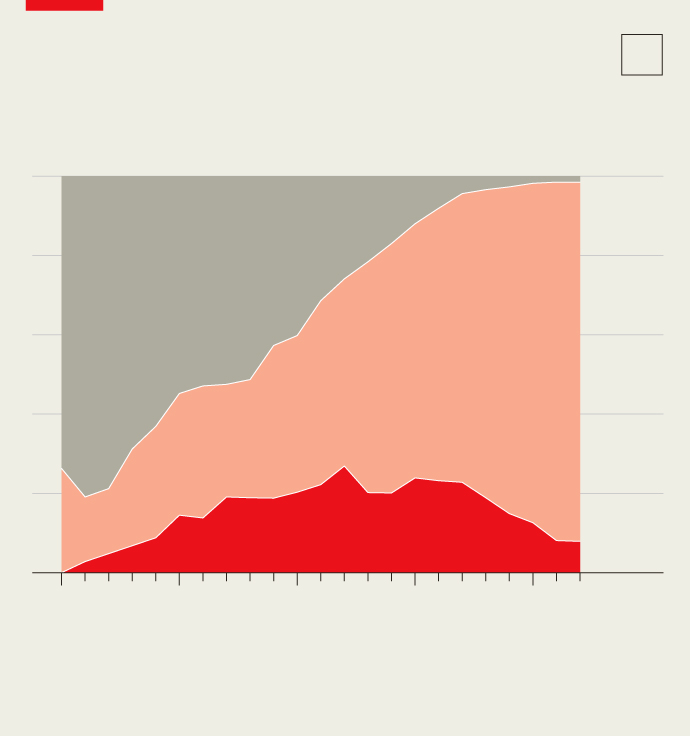

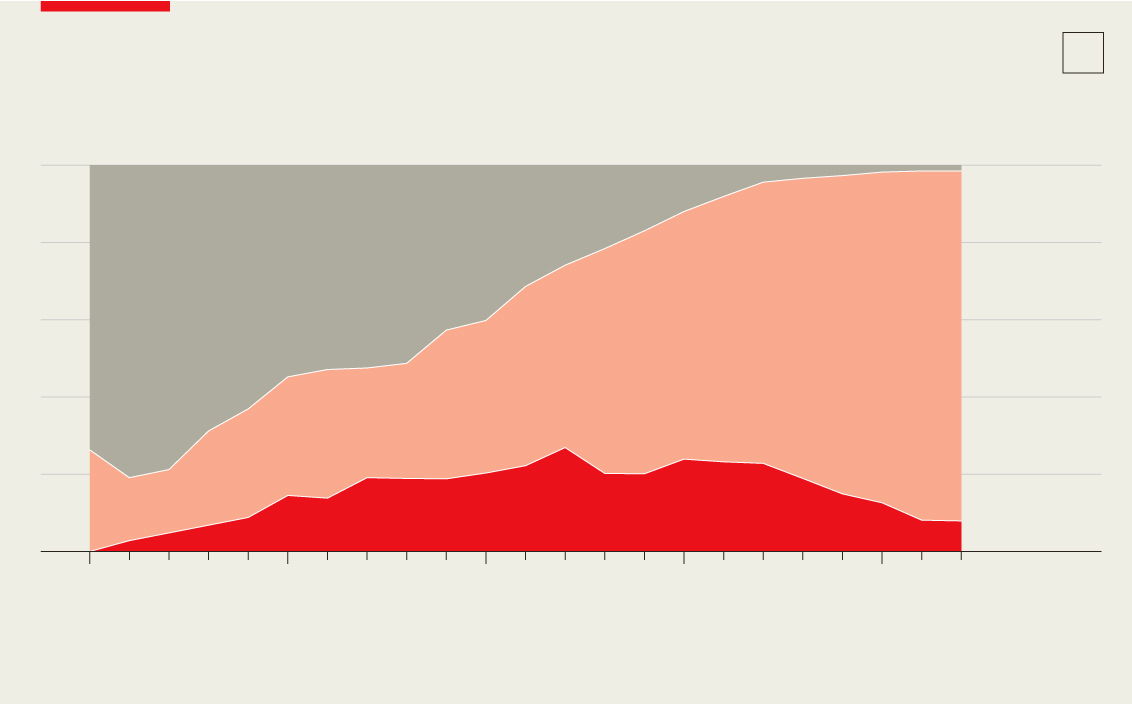

However, there's a problem: even if industry returns, the old jobs won't. The manufacturing sector produces more than in the past with less labor, a transformation very similar to that experienced by agriculture. The accessible, middle-class jobs that drew crowds to factory gates during the Fordist heyday have almost completely disappeared. According to our analysis, the jobs most similar to those in the manufacturing industry of the 1970s are not found in factories (now automated and capital-intensive), but in jobs such as electrician, mechanic, or police officer. All of them offer decent wages to those without qualifications.

Read also Why elite business school graduates struggle to find jobs The Economist

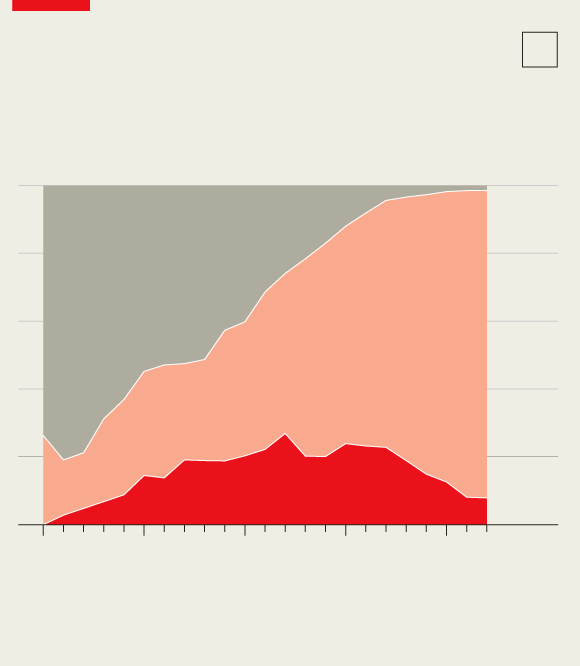

Nearly a quarter of the American workforce was employed in manufacturing in the 1970s; today, by contrast, fewer than one in ten workers are. Moreover, half of “factory” jobs are support jobs (such as human relations and marketing) or professional jobs (such as design and engineering). Less than 4% of American workers actually work in a factory. The United States is not unique. Even Germany, Japan, and South Korea (which run large trade surpluses in manufactured goods) have seen steady declines in the share of such employment. China lost nearly 20 million factory jobs between 2013 and 2020, more than the entire American manufacturing workforce. An IMF study calls this trend “the natural outcome of successful economic development.”

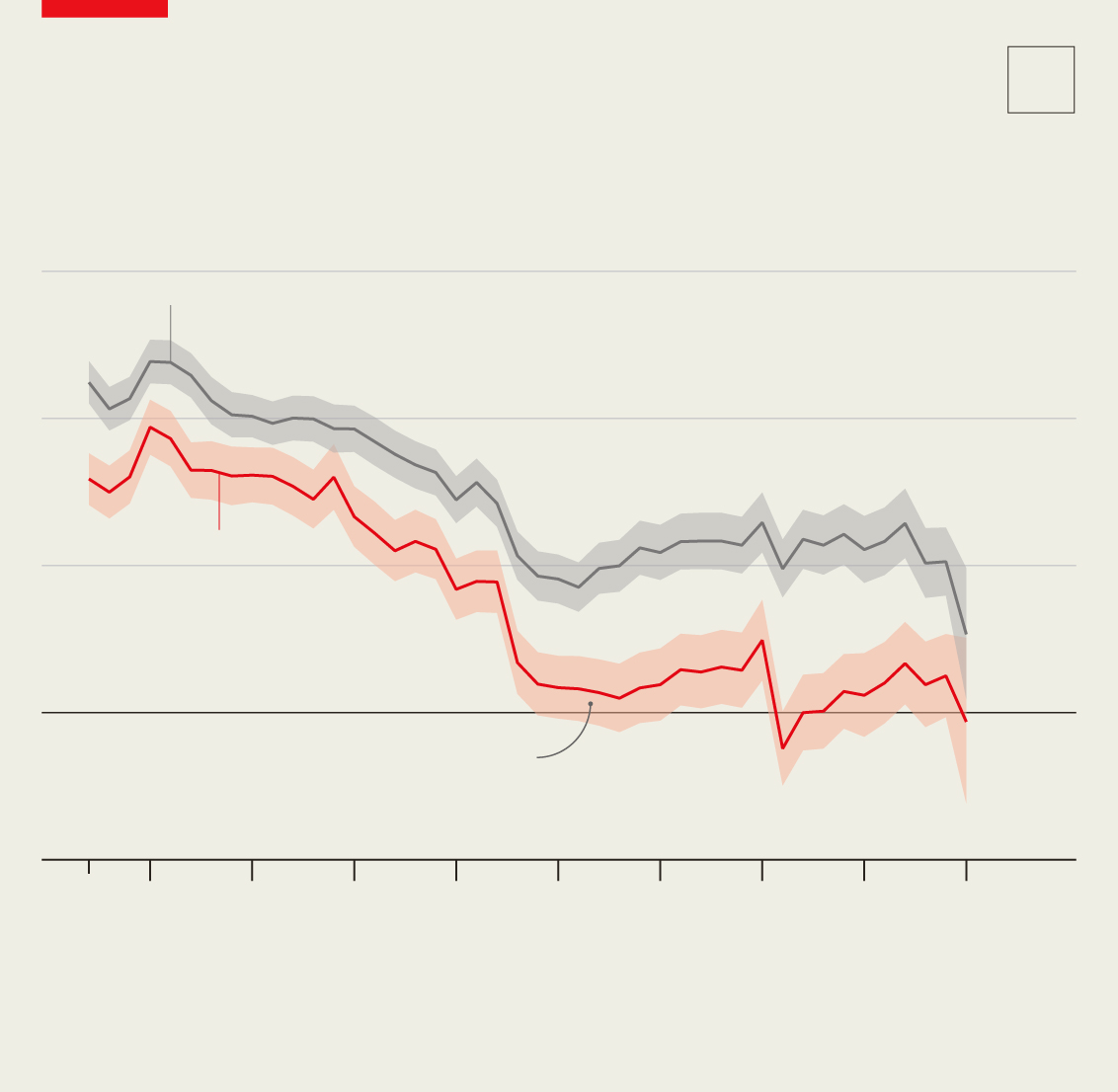

Source: RZ Lawrence, “Behind the curve: can

manufacturing still provide inclusive growth?”, 2024

Source: RZ Lawrence, “Behind the curve: can

manufacturing still provide inclusive growth?”, 2024

Source: RZ Lawrence, “Behind the curve: can manufacturing still provide

inclusive growth?”, 2024

As countries grow richer, automation increases output per worker, consumption shifts from goods to services, and labor-intensive production moves overseas. However, that doesn't mean industrial output collapses. In real terms, U.S. output is more than double what it was in the early 1980s; the country produces more goods than Japan, Germany, and South Korea combined. As the Cato Institute, a think tank, points out, U.S. factories alone would rank eighth among the world's largest economies. Even a heroic reshoring effort that eliminated the $1.2 trillion trade deficit would have little effect on employment. In the production of that amount of goods, about $630 billion of value added would come from manufacturing (the rest would be attributed to raw materials, transportation, and so on).

According to calculations by Robert Lawrence of Harvard University, given that each manufacturing worker generates about $230,000 in value added, restoring enough production to fill the gap would create about 3 million jobs, half of them in factories. This would increase the share of labor in manufacturing by just one percentage point. Suppose such a result were achieved by applying an average effective tariff of 20% to all $3 trillion of US imports, prices could rise by about $600 billion, or $200,000 for each manufacturing job "saved."

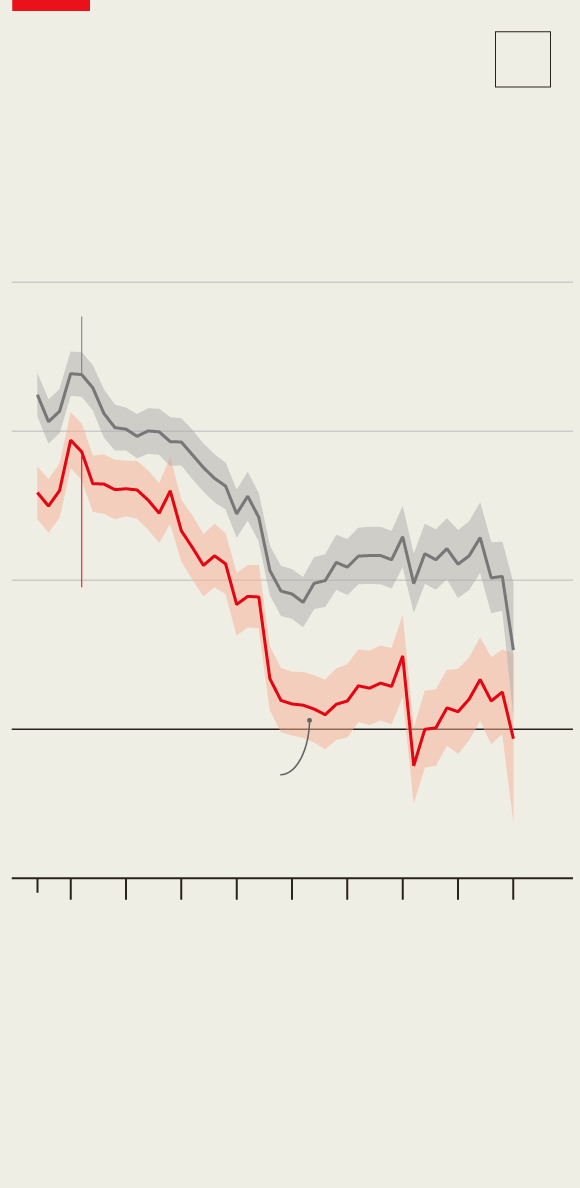

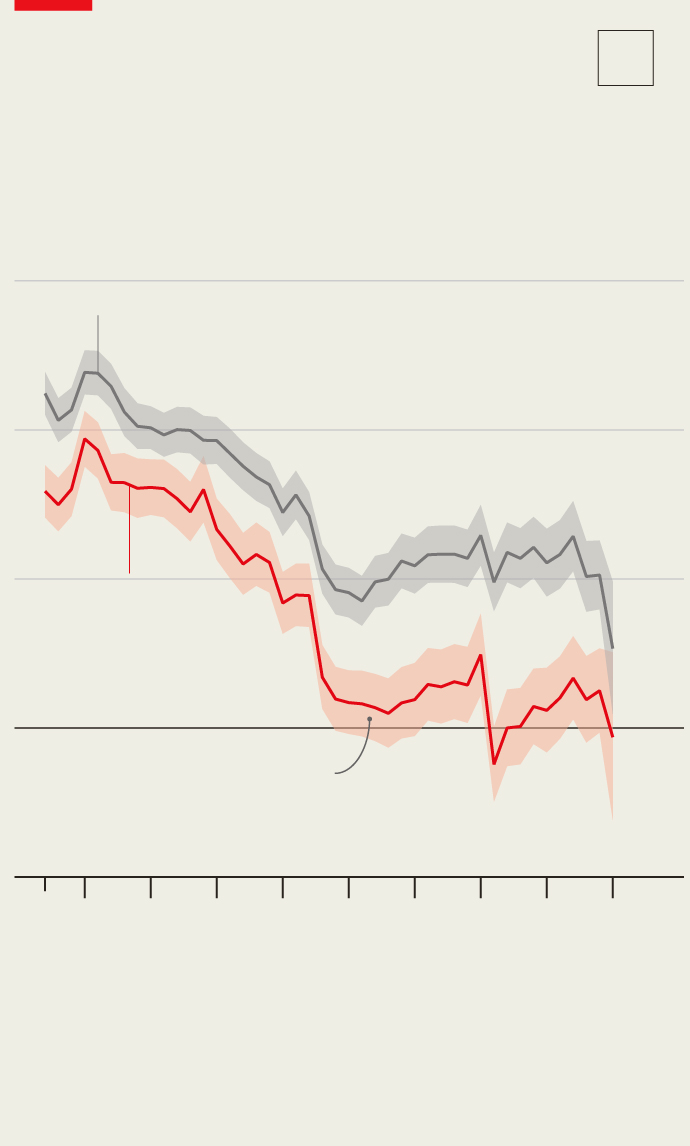

It's a high price to pay for jobs that are no longer as attractive as they once were. Seven decades ago, factories offered a rare package: good wages, job security, union protection, plentiful jobs, and no degree requirements. In the 1980s, manufacturing workers still earned 10% more than their counterparts in other sectors of the economy. Their productivity was also growing more rapidly.

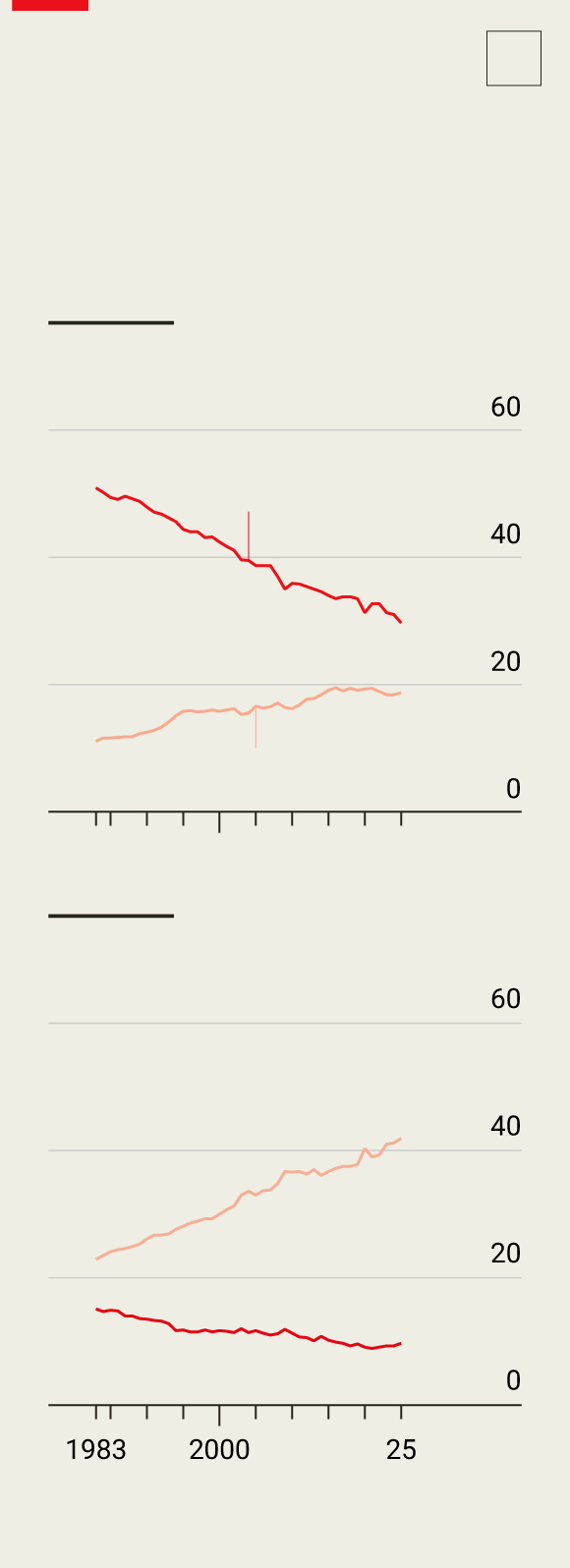

*Taking into account age, education, ethnicity, gender, marital status, and other factors.

† Until March

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

*Taking into account age, education, ethnicity, gender, marital status, and other factors.† As of March

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

*Taking into account age, education, ethnicity, gender, marital status, and other factors.

† Until March

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

Today, factory work lags behind unskilled service-sector jobs in hourly wages. There has also been a collapse in the manufacturing wage premium, which compares the earnings of similar workers across factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, and others. Using methods similar to those of the Commerce Department and the Economic Policy Institute, we estimate that by 2024, the premium will have fallen by more than half since the 1980s. For those without a college degree, it has completely disappeared, although such workers still enjoy a premium in the construction and transportation sectors. Productivity growth has also slowed: output per manufacturing worker now grows more slowly than that in the services sector, suggesting that wage growth will also be weak. A crucial component of the proposition that “factory jobs are good jobs” no longer holds.

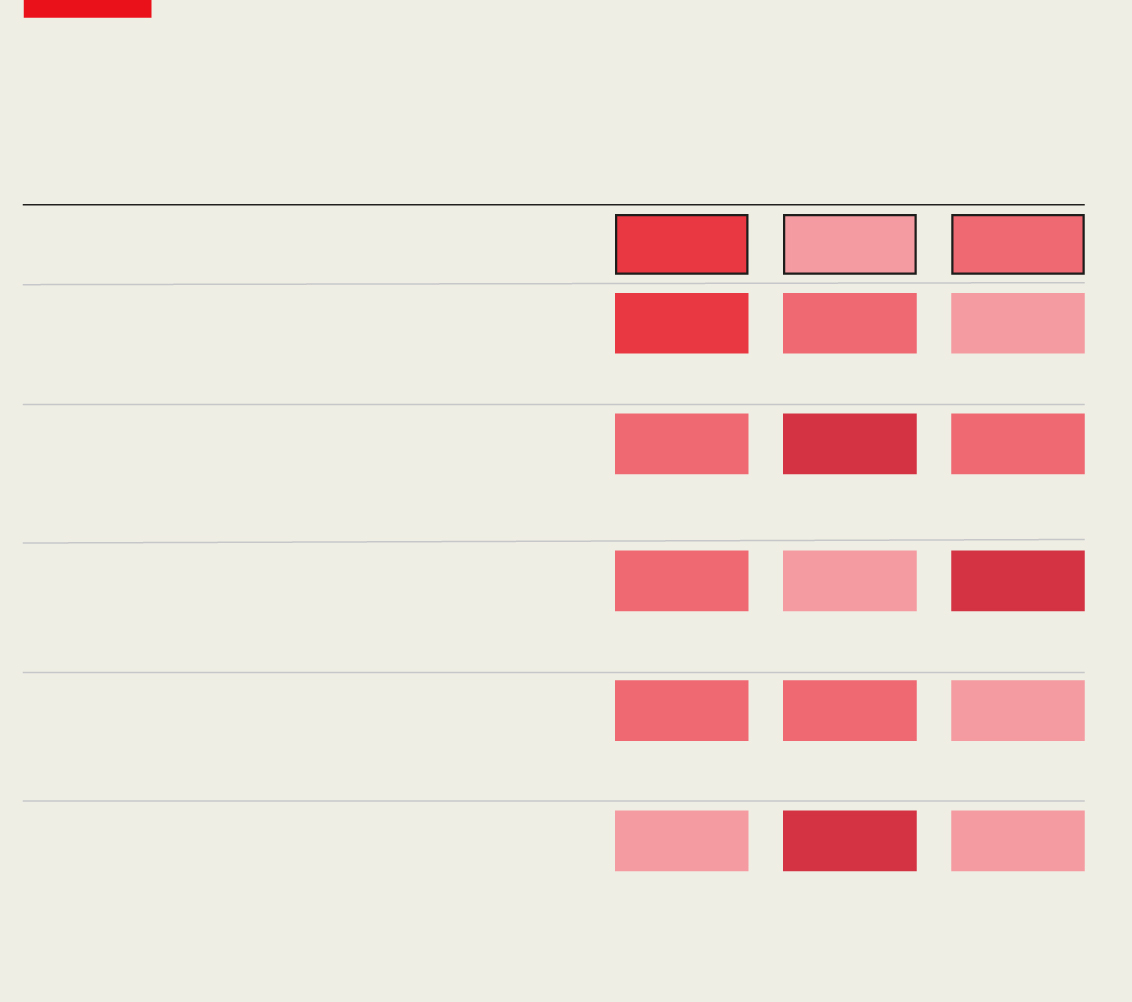

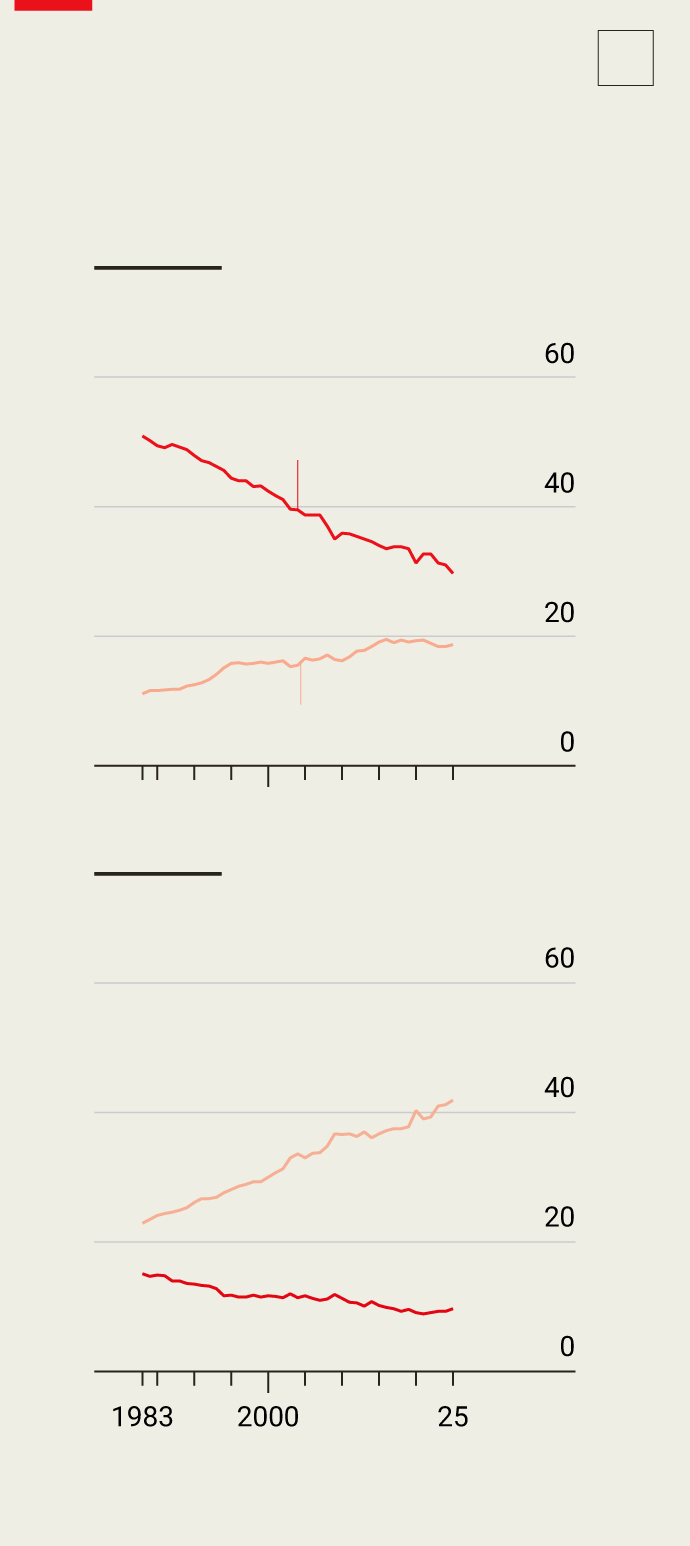

Job boom

white collar

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

Job boom

white collar

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

Rise of white-collar work

Sources: Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts; The Economist

Furthermore, it's not easy to find a job in manufacturing. Modern factories are highly technical and run by engineers and technicians. In the early 1980s, assembly workers, machine operators, and repair workers made up more than half of the manufacturing workforce. Today, they represent less than a third. White-collar professionals far outnumber blue-collar workers. Moreover, even once found, factory employment is much less likely to be unionized than in previous decades, with membership falling from one in four workers in the 1980s to less than one in ten today. To find the modern equivalent of these jobs, we looked for jobs with the same characteristics.

What offers a living wage, unionization, no degree requirements, and can absorb the male workforce? The result: mechanics, repair technicians, security workers, and skilled trades. More than 7 million Americans work as carpenters, electricians, solar panel installers, and other similar trades; almost all are men and lack degrees. The median wage is $25 an hour, unionization is above average, and demand is expected to increase as the country modernizes its infrastructure. Another 5 million work as repair and maintenance technicians (think HVAC technicians and telecommunications installers) and mechanics, with wages well above the factory average. Emergency and security workers also share similarities: more than a third are unionized. However, these jobs differ from factory jobs in one respect: there are no cities dedicated to a single HVAC company. Factories once powered cities and created demand for suppliers, logistics, and bars. The new jobs are more dispersed and therefore less likely to boost local economies. However, even if the benefits are diffuse, they are almost as significant. Nearly as many people work in these categories as held manufacturing jobs in the 1990s. With better wages, lower qualification requirements, and stronger unions, they appear more attractive to the American working class than modern factory jobs.

Read also Is the US economy capable of coping with mass deportations? The Economist

And the future is moving even further away from factories. According to official forecasts, skilled trades and repair workers should experience 5% growth over the next decade, while the number of manufacturing jobs is expected to decline. The fastest-growing categories for workers without a degree are healthcare and personal care, expected to grow by 15% and 6%, respectively. These include positions such as nursing assistants and childcare workers, and they bear no resemblance to old-fashioned manufacturing jobs due to their low wages. The task, as Harvard's Dani Rodrik says, is to boost the productivity of the jobs that are actually growing. Perhaps that could include ensuring the adoption of artificial intelligence, whether for medication management or diagnostics.

At the end of the 18th century, Thomas Jefferson considered agriculture the foundation of a self-sufficient republic. Influenced by the French physiocrats, who considered agriculture the noblest source of national wealth, Jefferson believed that working the land was the path to freedom and abundance. In the 20th century, factory work inherited that symbolic role. However, like agriculture in earlier eras, manufacturing jobs are also vanishing with increasing prosperity and productivity. The heart of the American working class now beats elsewhere.

© 2025 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved

Translation: Juan Gabriel López Guix

lavanguardia