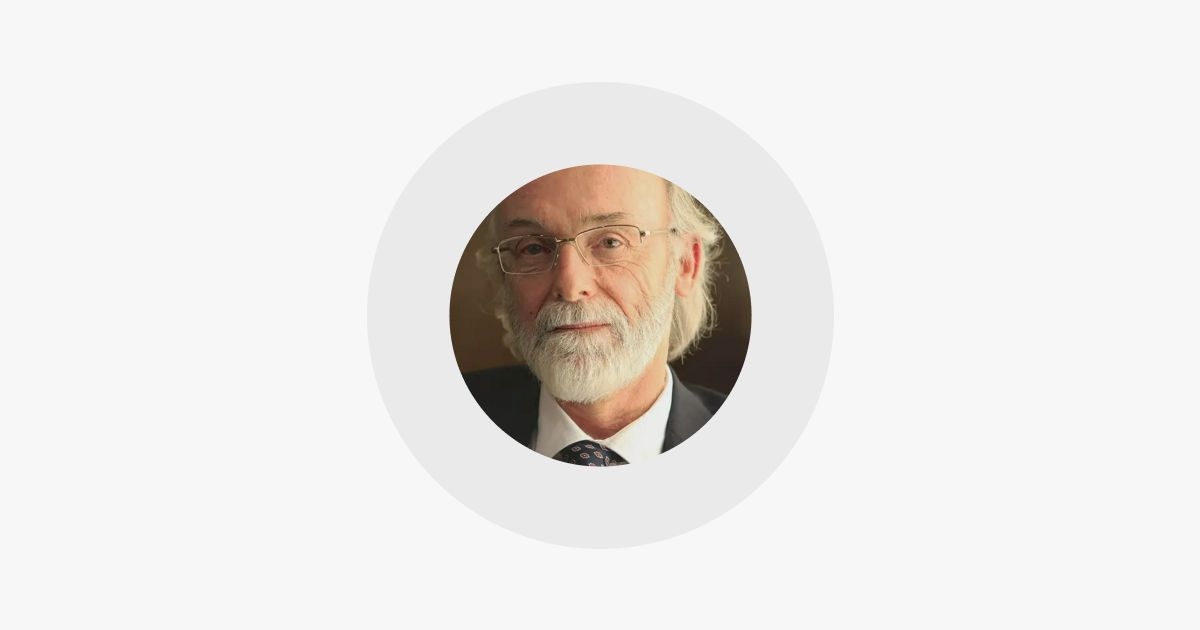

Eduardo Gageiro. The lens of Freedom

He said that photography is a “mechanical art”. “It captures the moment, an expression, a feeling, an event that will never be repeated”. He immortalized some of the historic moments of the 25th of April that consecrated him as one of the greatest Portuguese photographers of the 20th century: the meeting of the military in Terreiro do Paço, the attack on the PIDE headquarters, the political police of the dictatorship, and the moment when Captain Salgueiro Maia realized that the revolution had triumphed… One of his most iconic photographs shows a soldier taking the photograph of the Portuguese dictator from the wall, a symbol of the change that had occurred. He said several times that this was the happiest day of his life.

During the dictatorship, he captured, through his lens, the precarious conditions in which a large part of the Portuguese population lived, and was arrested several times by the PIDE. “It left a huge impression on me. I couldn’t look through the double bars; seeing the butterflies and birds outside caused me incredible anguish. And precisely to avoid seeing those bars, I would turn to face the wall. That traumatized me so much that for years I couldn’t be in a place without having something to look at. But they didn’t hurt me,” he said in an interview with Nascer do SOL in 2014.

He always carried his camera on his shoulder: “I always, always, always carry my camera. I wouldn’t have taken many of the photos if I hadn’t carried it. If I’ve ever lost photos, it was because I was talking. Nowadays, if I’m at an event, I don’t talk to anyone. I have to be 100% focused. Sometimes my colleagues even get angry,” he admitted at the time.

Before becoming a photographer, when he worked at the Fábrica de Loiça de Sacavém between 1947 and 1957, he always had photographs in the drawer that he coloured by hand, which earned him a few scoldings from his boss. But as he revealed in the same interview, “not everything was negative”, since there he spent his daily time with painters, sculptors and factory workers, who influenced his decision to do photojournalism.

Eduardo Gageiro died in the early hours of Wednesday, aged 90, at the Hospital dos Capuchos, in Lisbon, “in peace, surrounded by his family, with all the love and comfort”, his grandson, Afonso Gageiro, told Lusa, also revealing that his grandfather “maintained enormous willpower and mental agility, overcoming the prolonged illness that claimed his life”.

He was born in Sacavém in February 1935 and, at just 12 years old, he published his first photograph in the Diário de Notícias, with front page honors. It was in 1957 that he began his career as a photojournalist for the Diário Ilustrado. In addition to this, he was a photographer for O Século Ilustrado, Match Magazine, editor of the magazine Sábado, and worked for the Associated Press (Portugal), the Companhia Nacional de Bailado, the Assembleia da República, the Presidency of the Republic, for Deustche Gramophone – Germany, Yamaha – Japan and for Cartier, as listed in his biography on his official website, where we have access to his vast portfolio. In 1975, the World Press Photo competition awarded him the second prize in the Portraits category with an image of General António Spínola for the daily newspaper O Século, dated January 1, 1974.

“I heard about the coup through friends, who called me and said: ‘Now it’s time. Go to Terreiro do Paço. Bring all the rolls’. And I went. But when I got there, there was a soldier who told me ‘You can’t go through’. And I said with a big nerve: ‘Please take me to the commander, I’m his friend’. I wasn’t friends with the commander, I didn’t even know who he was. So the soldier, naively, said to a colleague: ‘Take this gentleman to the commander’. I got there and introduced myself. And the guy said: ‘Salgueiro Maia’. Believe it or not, on my word of honour, the guy knew me, because of the covers I did for O Século Ilustrado. ‘You can come with me’”, he recalled in 2014, referring to the day of the Carnation Revolution.

During his long career, he photographed in more than 70 countries, including dictatorships: Iraq, Cuba, the Soviet Union, China, Israel, etc. He ended up working freelance and never abandoned his trademark: black and white. “It’s more direct, more dramatic. I also like it because I’m the one who develops the rolls and enlarges the photographs. I’m there all the way – from the moment the film is taken to the end. It gives me a pleasure that I don’t want to know about”, he shared with our newspaper.

Jornal Sol