İsmail Fatih Ceylan wrote: Şule Yüksel Şenler's prison life

Şule Yüksel Şenler lived as a fugitive in secret residences in Bursa and Istanbul for months due to a case filed by Bandırma Prosecutor Nusret Doröz. With the help of an Izmir businessman, she had her case transferred to Izmir and was acquitted. After this difficult period, she resumed her writings and conferences, which attracted widespread attention.

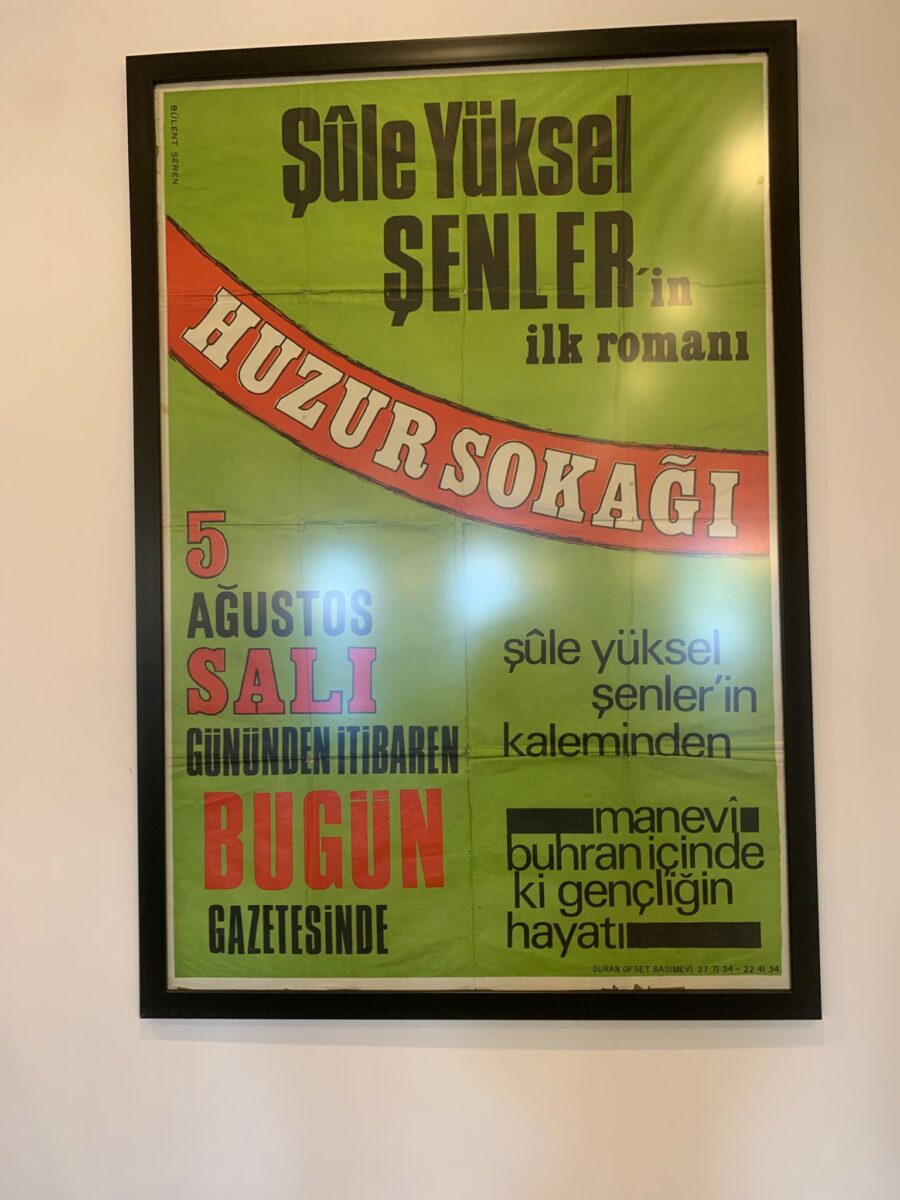

After a while, he achieved greater fame with his novel Huzur Sokağı, which was serialized in Bugün newspaper, and as a result of the great interest of this novel, Huzur Sokağı was made into a movie called Birleşen Yollar.

During the time when Birleşen Yollar (Birleşen Yollar) was being shown in theaters and causing a storm, Şenler married her theater fiancé. Her family and close circle didn't actually like the prospective groom, finding him unsuitable for Şule Yüksel Şenler. However, Şenler chose this marriage because it offered her the opportunity to give a lecture with her theater husband. While her husband was performing his play as Hz. Ömer in the city they visited, she could give her lecture the same day or evening.

Şule Yüksel Şenler's marriage was also on the press agenda. The wedding was reported in full detail in the İnci supplement of Tercüman newspaper.

Her mother, Umran Hanım, cried a lot at the wedding, which was held for the ladies during the day and the men at night. That's why Şule Yüksel wasn't very happy.

The wedding took place during the groom's leave from military service, and he was due to return to the military base in two days. The groom had an important warning for his two-day-old bride.

"Lady, don't close our house! Let your family come and go, stay for two days, three days, five days, but come back home again."

But Şule Yüksel's family couldn't accept this situation. Torn between her husband's warning to "stay home" and her mother's insistence, who had always opposed this marriage, to "stay with us," she was distressed. Although her mother wanted her to close her house and stay with them, she insisted she would act according to her husband's wishes. She called her husband and told him to vacate his Ankara home and move there. And so she did. To avoid being caught between two choices, she would continue her journey away from her family, yearning for them, in another house, in another city, under her new identity and surname. But her family, who had supported her for years, was heartbroken and resentful of their daughter.

Şule Yüksel, whose husband was serving time in the military, had spent four months trying to adjust to a life alone in Ankara when she was sentenced to 13 months and 10 days in prison for "insulting the President." Şule Yüksel was once again in the headlines.

The news that the new bride, Şule Yüksel, was going to prison caused a huge stir. Her loved ones were practically on edge. Letters were piling up demanding her pardon, sent to the President, the Prime Minister, and Parliament. Demonstrations were held wherever the Prime Minister was traveling, voicing their opposition to the decision. The moment Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel began speaking from the podium, they interrupted him, shouting, "No to Şule Yüksel's arrest!" and rallied to have the decision overturned. Prime Minister Demirel would stop mid-speech and declare, "You're right!"

The newspaper's editor-in-chief, Hilmi Karabel, who had been sentenced in the same case, surrendered immediately, hoping to finish his sentence as quickly as possible. This was also Şule Yüksel's wish. Even though there was a four-month postponement, the press would continue to insist on a wide range of articles being written about her. The rumors that she was "on the run" particularly hurt Şule Yüksel.

Despite his belief that "we will go to prison if necessary for this cause, we will not abandon our cause even if it means the gallows," he was devastated by his status as a fugitive. While preparing to surrender, his wife prevented him.

"Maybe a press amnesty will be issued during this time, and you won't go to jail!" he said, forcing her to go to his sister in Eskişehir. There was a possibility of being forcibly imprisoned until the petition for a postponement was received. The police were searching for Şule Yüksel, a fugitive. She was taken to Eskişehir to live with her sister-in-law.

Less than a month later, the March 12 memorandum was implemented.

The memorandum was initially greeted with applause by leftists. Finally, the army had taken action against the growing reactionism. Newspapers reported, "The heroic Turkish army has finally seized power." The Republic was being saved, and Kemalism was being reestablished.

Islamic newspapers were shut down, and Mehmet Şevket Eygi was forced to flee the country. The religious community, which had been growing amidst great activity, suffered a heavy blow. Comments were being made that "the development of Islam and the awakening of the people" were being punished by the military.

However, things took a turn for the worse after March 12th shut down the TİP (Turkish Workers' Party) and began prosecuting prominent left-wing writers. Figures like İlhan Selçuk were tortured at the Ziverbey Mansion, while left-wing youth leaders like Deniz Gezmiş, Mahir Çayan, Ulaş Bardakçı, Hüseyin İnan, and Yusuf Aslan were captured and arrested.

In addition to the TİP, the National Order Party, which Erbakan had founded and to which the public had begun to show interest, was also shut down for "anti-secularism." Erbakan also went abroad.

Şule Yüksel's conviction came at a difficult time in every sense. With the newspaper closed, she could no longer write or give conferences. More importantly, her family was disgruntled. She had a brother named Üzeyir who occasionally cared for her. Şule Yüksel Şenler felt lonely.

As his four-month deferment was nearing its end, Üzeyir visited his brother's mother-in-law in Bursa. They researched which prison would be suitable and decided on Bursa. They learned that the Bursa prosecutor, despite being a leftist and Alevi, was supportive of the women in prison and didn't allow them to be oppressed.

Since no press amnesty had been granted during the waiting period, he would now surrender and serve his sentence. He called the prison warden. He wanted to serve his sentence in this prison and asked if it would be possible to come and see the cell where he would be staying.

"Oh, Ms. Şule, what are you saying?" asked the Director. "Even though we disagree, this place is no place for a lady like you. Why did you choose this one, with its single cell and full of common criminals, when there are fully equipped, modern prisons? You could never do it here!"

Şule Yüksel stated that she was determined and would explain her reasons when they met face to face, and reiterated her desire to see the prison. She and her brother, Zübeyir, went to the prosecutor's office. While Şule waited outside, an elderly prosecutor emerged from the door. When he saw Şule Yüksel, he spoke in surprise.

"Ms. Şule, are you really going to go in? Are you going to serve time in Bursa Prison?" he said.

“That’s why I’m here.”

"Ms. Şule, look, we may not be on the same wavelength, we may not have the same ideas, our opinions may be opposite. But you are a lady. It's unacceptable for someone like you to go to prison, let alone serve time in a prison like Bursa, where extremely unruly inmates are sent from all over the place!"

"Sir, I know these things, but my sentence has been given, execution is necessary, and I'm here. I went and saw the prison. I know the conditions, I knowingly chose this place. My duty is to serve whatever sentence I've been given here. It's not my place to disobey!"

Şule Yüksel had been married for eight months, and her husband was still in the military. She said goodbye to her husband, who was in the urology department at a hospital, in the garden one night before leaving for Bursa.

As he set out into those difficult and challenging days, he felt very alone and abandoned. Only his brother, Üzeyir, was with him from his family, who were upset about his marriage. He too had married and could not provide the same care he had before.

His mother, who had selflessly endured all his hardships with him, his father, who had given his all, and his sister Gonca Gülsel, who had been a friend and companion, were no longer with him. How he wished they had been with him on this journey to prison.

They had once traversed mountains and hills on arduous journeys, unwavering in illness and fatigue. Those happy days seemed so distant. Now it was as if they had never been a family.

"Really, we were six siblings, a large family, where are they now?" he would say. Why were they far away, where were they now, why all this abandonment, why this loneliness?

This situation was worse than being imprisoned; it brought a deep, heartbreaking pain every day. His crime was fulfilling his wife's wishes. He realized his marriage choice was wrong, and he felt a distinct anguish from it, but what did it mean to be so alone? He had made this sacrifice so his family could be relieved of their burden and find peace.

She cried as she remembered how her mother would wait for her while she wrote, serving her tea, saying, “You write, my daughter, so many of our girls thirsting for truth are enlightened by you,” and how she would say to her while she was in the hospital in Kayseri, “You go and hold your conference, my daughter, we are very late, those young girls shouldn’t be late.”

What about her father? Despite all the hardship he endured, he would say, "My daughter, it doesn't matter if we go hungry and thirsty and lose money for your struggle." How could he forget that when he first began writing, he would pick up her article early in the morning, take it on foot from Bahçelievler to Sultanahmet, deliver it to the newspaper, and return home on foot again?

What about Gonca? More than a sister, she was a friend and companion. She had worked tirelessly day and night during the engagement and wedding, taking care of everything her sister needed. When Şule began writing for the newspaper and then attending conferences, she had stopped writing herself. With her parents and Üzeyir also accompanying Şule, she had taken on the entire burden of the household. She had looked after Örsel, now named Göksel, who occasionally dropped by the house, little Tuncer, and their youngest sister, Çiğdem. She had become like a mother to Çiğdem.

Where were those selfless, self-sacrificing people who devoted themselves to Şule? Where was her family now?

Şule Yüksel was tired not of fighting, but of being broken. Her family was not with her, and she was resentful when she went to prison.

But his readers and listeners had come in droves, busloads of them, to see him off to prison. Some had even come from abroad. It was Parents' Day. They had come in droves, as if they were attending one of his conferences, surrounded him in groups, and showered him with a flood of love.

Şule was moved and wept at the outpouring of love. But what she was really crying about was not being able to see what she wanted to see amidst all the crowd.

Her eyes searched hopefully for her beloved mother and father. "Don't let my daughter catch a cold," her mother would say, putting her own ailing life aside as always to care for Şule. "My child, take care of yourself. We'll be with you until the end. I'd sacrifice everything for you. You're our pride," her father would say again... Where were they?

He was in the crowd, everyone hugging him, but his loneliness was wreaking havoc on his heart. He was alone, missing in the crowd. He had no mother, father, siblings, or newspaper. His novel, Peace Street, had been left unfinished when the newspaper closed. A memorandum had been issued, and people were living anxious days.

Nothing would ever be the same again.

Şule's dreams and struggle were left unfinished. Everyone who tried to silence her, who complained and dragged her from one hearing to the next, who questioned her, who judged her, had finally succeeded.

Yes, his loved ones never left him alone. They were the ones who bid him farewell in prison, amidst tears. As he entered the prison, unaware of the atmosphere or what awaited him, the crowd outside sang the anthem, "We will write Islam, the true path!"

In prison, Şule Yüksel was given a place on the top bunk bed. The stove's pipe ran very close to the foot of the bunk bed. The small children living in the cell were playing with the mice by their tails, catching them. Some were even still wearing diapers.

Their mothers would launder the rags superficially under soapless water and hang them by the stove. As the poorly rinsed rags dried, the acidic smell of the heat evaporated and rose to the ceiling, filling Şule Yüksel's sensitive lungs.

After a while, he became ill. The doctor who came to examine him entered with his nose blocked. As soon as the doctor entered:

"Ms. Şule, are you crazy? How can you lie here with your lungs in this condition?" he said.

He said he needed to be hospitalized. But the private hospital where he worked refused to accept the gendarmerie that would wait for his inmate. He was then admitted to Bursa State Hospital, but that required a medical report on his lungs.

Şule Yüksel was forced to travel back and forth between the prison and hospital perhaps thirty times. There were a crowd of inmates, both men and women, in the prison car. During the rides, the guard sat next to her in the driver's seat. Each time, they waited for hours in a derelict area on the hospital's lowest floor, where the heating pipes ran. She could never obtain the necessary medical report.

Kamil Günışık and his family, whose home Şule Yüksel stayed in Bursa for months during her days as a fugitive, were immediately aware of her problems and closely attended to her every need. Kamil Günışık's son, Tayyar Günışık, was responsible for fetching and transporting any necessary items to keep her comfortable in prison. The Günışık family, from the youngest to the oldest, was mobilized.

Kamil Günışık immediately stepped in to handle the hospital and reporting issues. To the doctor:

"You're reporting to leftists and Masons. Everyone benefits from your signature authority. Why aren't you doing anything for us?" he would scold, argue, and finally get the report. He would later learn that the doctor he reproached, "You're reporting even to Masons," was in fact a Mason.

Of course, not all doctors were the same. He encountered some who simply did what their profession required, without any ideological considerations. But there was one whose resentment and spite toward Şule Yüksel was unique. When he arranged for Şule Yüksel to be hospitalized:

He had given the order, “Prepare the isolation room!”

The isolation room was a freezing, damp room, previously used as a storage room, with nothing but a bed and a nightstand. It was impossible for a tuberculosis patient to sleep in these conditions.

The doctor didn't stop there; he warned the nurses against providing blankets and stoves. His tone was as if to say, "Let him die!" But as soon as he left the hospital, the nurses brought a small electric stove and a blanket to his room, and took them back the next morning before the doctor started work.

He had to go downstairs for physical therapy. He was so weak he couldn't even get dressed. He asked the nurses for one of their black capes and wore it like a trench coat. Every time they went downstairs for physical therapy, they had to pass through the outpatient clinic corridor, past the waiting patients.

As she walked along the corridor, armed gendarmerie officers flanked her, the crowd passed their verdicts. Some claimed she had committed theft, others that she might have committed another crime, while others spit on her as she passed, handing down their own punishment. This situation was deeply tiring for Şule Yüksel. Being left defenseless in the face of these insults, reliving the situation over and over again, was deeply distressing. Ultimately, she decided against physical therapy rather than endure such a life.

One day, he collapsed in the ward. He was speechless for five or six hours. Not a single word would come out of his mouth. He could only explain his troubles with pen and paper. A doctor was brought in. Only with an injection did he recover. He was rushed to Bursa State Hospital. There were no available private rooms, so he was admitted to the Mental and Nervous Diseases ward.

The fifteen-bed ward housed harmless but noisy mentally ill women. An armed gendarmerie guarded Şule Yüksel's bedside. Since there was no toilet in the ward, the gendarmerie followed her as she went to the shared restroom.

Despite her pleas, "Please step back a little, I'm shy!" he would come and stand right at the bathroom door. Sometimes, he would even stay a step away from her while she performed her ablutions. Seeing a mentally ill patient, Şule began protecting herself from the gendarmerie by pulling a sheet over her like a curtain when she performed her ablutions.

A week later, he was moved to a vacant private room. Finally, thanks to Kamil Günışık's efforts, the medical report was issued with great difficulty. He spent a month in the Internal Medicine Department, just to get a diagnosis.

The news Şule Yüksel received there deeply saddened her. Her sister, Gonca Günsel Şenler, had gotten married and was going to Denmark with her husband. She hadn't been able to see her sister's wedding, and perhaps wouldn't see her for many years after she left for another country. Yet, she had fought so hard for Şule, so desperately. This separation gripped her deeply, and her heart ached.

After the internal medicine department, they took her upstairs to the Pulmonology Department for treatment. They kept her waiting in the hall for quite some time. The doctor had prepared a tiny, moldy room in a storage area, without heating or a stove. They placed a mattress on top of it, and Şule lay on a thin blanket. She was cold, but the doctor had strict orders: No blankets, no stove, nothing.

After two or three days there, the doctor called the Gendarmerie Command and, without anyone's knowledge, hastily discharged Şule Yüksel. However, according to the committee's report, she would be hospitalized for a month and receive hospital care.

Despite the doctor's hostility, the nurses were very attentive to Şule Yüksel. In the doctor's absence, nurses and patients crowded into almost every hospital room.

Two months had passed since Şule's imprisonment. Thousands of people, unable to bear Şule's imprisonment, continued to flood the President with letters.

As the backlash mounted, President Cevdet Sunay issued a statement, announcing that he had pardoned Şule Yüksel Şenler. While everyone was jubilant and awaiting her release, Şule Yüksel announced that she had rejected the pardon.

"I consider this pardon an injustice," he said. "I would rather suffer the punishment and walk around with my forehead clean and my head held high than be pardoned and walk around with my head held low," he said, rejecting this pardon.

The poor prison conditions, the constant coughing fits that worsened due to the environment, and the unhealthy conditions of her ailing body made her even sicker and more exhausted. Yet, she remained uninhibited, unsullied, and took personal care of the inmates. Except for two individuals, the entire cell wore headscarves. Her teaching of the Quran, practical knowledge, and religious practices earned her praise from the prison warden.

Bursa newspapers had reported, "Şule Yüksel's literacy and Quran course." Serving her sentence inside, Şule Yüksel was on the minds and attention of those outside. Visitors flocked from all over the country, never leaving her alone behind bars, trying to make her feel alone.

Once, at the beginning of Ramadan, a university student visited and was moved to tears by the conditions. Soon after, the young man received news. On his way there, the young man had made an agreement with a restaurant. A large tray of every dish prepared during Ramadan would be prepared and sent to Şule Yüksel. He paid the restaurant a month's expenses in advance and returned to Istanbul in tears. For thirty days, this large tray, filled with a variety of dishes, reached Şule Yüksel.

This close attention from a stranger she'd only met once made Şule Yüksel's wounded and broken heart bleed. The morsels choked on her food and she found herself gasping for air in the muddy courtyard.

"My mother! My father..." she cried every time she went out into the courtyard. It was always her mother, always her father. Şule's cries reached even the prison administration.

After 13 months and 10 days of difficult and suffering, some of which were spent between the hospital and the ward, he was finally returning home.

But Şule wasn't particularly happy about being released; she couldn't fully experience the feeling of freedom. Everyone was overjoyed, and crowds had once again surrounded her. Women and young girls from all over were embracing her with tears in their eyes and sniffing her.

But Şule, still unable to see her family, lived in loneliness among the crowd. She was without a mother or father. Gonca had married and moved to Denmark. After her discharge, her husband, who visited her at frequent intervals, always started fights over inappropriate things, shouted insults, made her cry, and once knocked her unconscious at the visiting area.

The place called the dungeon was more peaceful. There, he was instrumental in guiding so many people, a whole ward full of women. Even Deniz Gezmiş's friend, the prosecutor, eventually began calling him to ask questions. Once guided, the man, who had never fasted, fasted for a month during Ramadan.

His wife came:

“What did you do to my husband?” she asked in surprise. “How could you change him?”

Life in prison was difficult, but life outside would be even more difficult. She knew that returning home would lead to difficult times with her abusive husband that would make prison seem like a nightmare. The real pain was that she wouldn't be able to tell anyone about this.

A period was beginning for him when he would say, “I won’t complain to anyone, I’ll just cry for my situation.”

Medyascope