You don't have to give up Harry Potter to quit J.K. Rowling

I genuinely feel for younger people, who will never have the pleasure of experiencing the unproblematic version of Rowling and her novels. For millennials and Gen Z kids like mine, there was once a golden era when you could just daydream all day about getting your invitation to Hogwarts without any associations with a full-time transphobe. Now, there's a new Harry Potter series coming to HBO, Rowling is busy tainting her legacy by gloating on social media about anti-trans legislation, and we have to decide what kind of relationship with the author's work is tenable for us. I don't believe we have to entirely give up Harry Potter to quit Rowling (nor do I suspect for many of us that's even possible) — but it is complicated. I have a degree in conflict resolution, and I know that when a person whose work you admire does things you really don't, it can — and should — create a moral conflict. But with some established negotiation tools, we can arrive at our own individual, ethical-ish criteria for engaging with controversial figures and their art.

Transformative mediation has been gaining traction in recent years, thanks to its more holistic, nuanced approach to conflict — and its understanding of the emotion that's so often baked into it. It diverges from traditional, arbitration-inspired models where there are ultimately winners and losers, right and wrong, focusing instead on reflection and empathy to create empowering outcomes. You can see the hallmarks of it in the reconciliation aspects of post-Good Friday Agreement Northern Ireland relations, or in how Sarah Sherman sensitively handled Aimee Lou Wood's criticism of her unflattering recent "White Lotus" sketch to resolve the problem.

LONDON, ENGLAND - JULY 30: J. K. Rowling attends the press preview of "Harry Potter & The Cursed Child" at Palace Theatre on July 30, 2016 in London, England. (Photo by Rob Stothard/Getty Images)

LONDON, ENGLAND - JULY 30: J. K. Rowling attends the press preview of "Harry Potter & The Cursed Child" at Palace Theatre on July 30, 2016 in London, England. (Photo by Rob Stothard/Getty Images)

So-called "cancel culture" usually just means "not rewarding bad behavior."

A fluid and nonjudgmental approach, especially in a dilemma involving so-called "cancel culture" (which, by the way, usually just means "not rewarding bad behavior"), helps us reconcile our own often inconsistent approach to our art and entertainment. It also allows space to recognize that other fans have different interests and positions and are going to make other choices. It's easy, for example, for me to detach from Rowling's wizarding world now that my kids are grown; it's a different story for someone whose middle school years were shaped by those novels, or parents whose children are still deep in their Gryffindor eras.

As with other creative artists who have, over time, revealed themselves on a spectrum ranging from dubious politics to weird wellness practices to outright criminality, the negotiables will vary according to the severity of the person's actions and the depth of our own relationship to the work.

There's no one right formula here. A transformative process would invite you to consider how meaningful Harry Potter is to you, where his creator’s behavior stands relative to your values, and what compromises you can realistically stick with. Because at some point, you may really miss those books. Or someone in your life will ask if you want to watch the new show with them, or suggest one of the books as a birthday present for their kid.

Rowling is an instructive example of the complexity of fan conflict and engagement, because her work doesn't stand alone. If you are appalled by her harmful anti-trans statements and actions, do you disengage from the film franchise as well, which is also the work of its directors and of the cast members who have spoken out against her? Do you choose not to support her book sales, but keep the editions you have, or buy secondhand copies that would support a local bookseller? Will you watch the new HBO series? Will you cancel your subscription? And if you decide everything to do with her is off limits now in your life, what policies will you implement when your children do want to read those books and watch those movies?

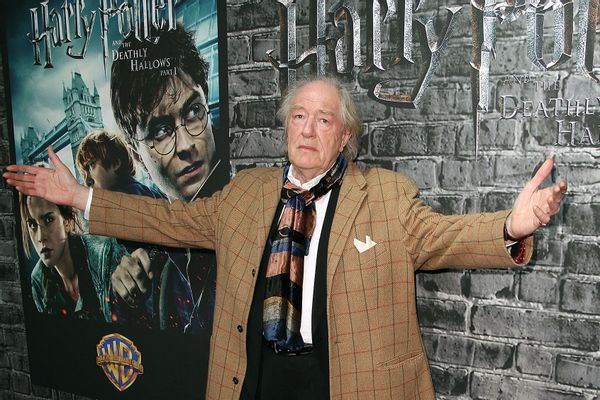

Michael Gambon attends the grand opening of Harry Potter: The Exhibition at the Discovery Times Square Exposition Center on April 4, 2011 in New York City. (Taylor Hill/FilmMagic/Getty Images)

Michael Gambon attends the grand opening of Harry Potter: The Exhibition at the Discovery Times Square Exposition Center on April 4, 2011 in New York City. (Taylor Hill/FilmMagic/Getty Images)

A blanket "separate the art from the artist (and her lucrative brand)" policy is always an intellectually lazy argument.

J.K. Rowling isn't Harry Potter. But a blanket "separate the art from the artist (and her lucrative brand)" policy is always an intellectually lazy argument. It wrongly implies that art exists independent of the person who creates it — and that it can be separated from the person who loves it. Given new information, we have a responsibility to reassess the work we care about. But that can run a gamut, because the things we care about make up our identity, too. Maybe you were never an R. Kelly fan anyway, so your relationship with "Ignition" isn't corrupted by his crimes. But maybe you have cherished your Alice Munro novels, and the accusations of abuse from her daughter give you new unease when you look at your bookshelf.

This all inevitably gets even trickier, because a major aspect of the quandary we face with difficult artists is financial. And the greater their fortunes, the more culpable we all are. J.K. Rowling is worth hundreds of millions of dollars, and every action that puts more money in her gargantuan bank account — money that she, in her own words, "definitely" funnels to anti-trans groups in the UK — is at least a partial endorsement of her behavior. Chris Brown still tours because people still buy tickets to his shows, and those sales help pay his bail money. Tangled up among the philosophical questions of how to regard certain artists will always be the considerably challenging one of ethical consumption. That's why it's easier to give the long dead a wider berth — I'm not paying for antisemite Richard Wagner's lavish lifestyle if I go see a production of "Parsifal."

I can think that Pablo Picasso and John Lennon were abusive men and be moved by Guernica and "Abbey Road," and respect that others approach their work differently. Terrible people can make great, meaningful stuff. We can't pretend otherwise, and we can't throw a cloak of invisibility over that stuff either; it would be a cultural loss if we did. But what we can do is be thoughtful about where to put our money and attention, and consider creative works in the context of the actions of their creators. It's a transformative, challenging way of looking at the world. And as Dumbledore would say, it’s the choice between what is right and what is easy.

salon