The Lure of Yesteryear Manufacturing

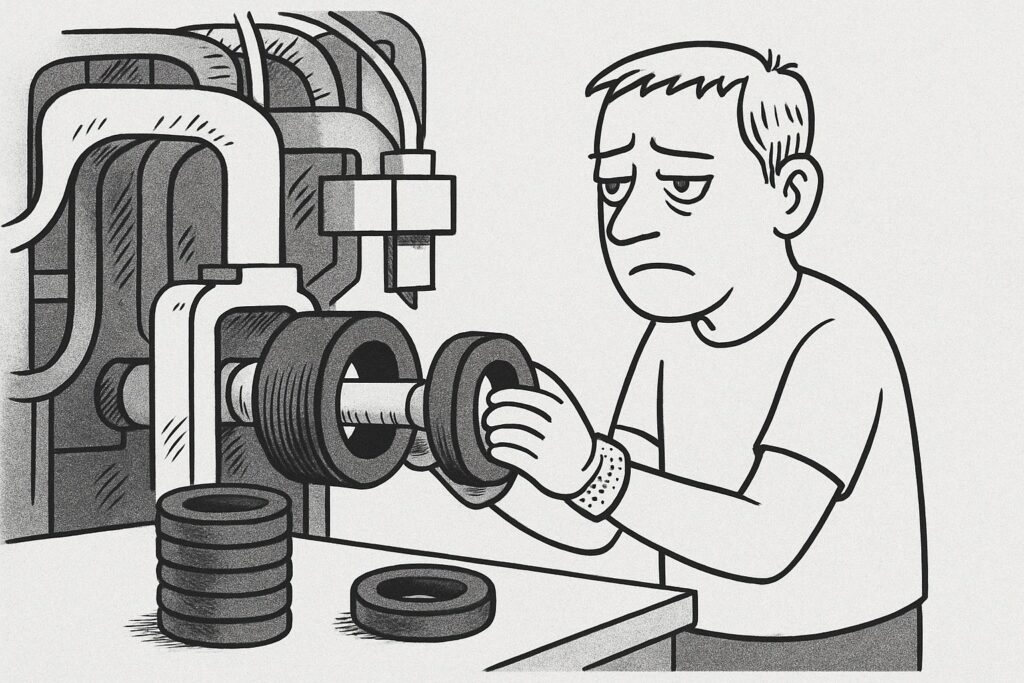

An eight-second Wall Street Journal video clip illustrates the old-time, labor-intensive manufacturing that some, including the two last US presidents, want to bring back to America by using state coercion and threats (“Trump’s Tariffs Are Lifting Some U.S. Manufacturers,” May 4, 2025). The featured worker in the video clip seems to be endlessly repeating two mechanical operations on a machine. The employer is an Ohio manufacturer looking to boost its production—and its prices, which will be bid up—following the 145% tax that Donald Trump imposed on Chinese imports.

The repetitive and mindless job shown on the clip is typical of old-time, labor-intensive, low-tech, “dirty,” often dangerous manufacturing, which has been mostly eliminated from the United States and other rich countries by two factors: automation and, for the rest, reliance on the comparative advantage of poorer countries at a lower stage of development and labor productivity. Bringing old-time manufacturing back to America, besides diverting resources from industries where labor is more productive and better paid, would also bring back repetitive jobs. Otherwise, it would not increase employment as the labor market is already at, or close to, full employment. The very process of bringing old manufacturing to the US, notably with tariffs and other Colbertist interventions, could further compromise full employment, creating another problem instead of solving a non-existent one.

About mindless manufacturing jobs, which were once common in now-rich countries, Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations (Book 5, Chapter 1):

The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life. …

But in every improved and civilized society this is the state into which the labouring poor, that is, the great body of the people, must necessarily fall, unless government takes some pains to prevent it.

Revealed preferences suggest that repetitive manufacturing jobs are still preferable to pre-industrial life or scavenging dumps in underdeveloped countries. In the 19th century, most workers outside agriculture, construction, and the resource industries were employed in mindless manufacturing. Of course, these workers are as worthy of our respect as the consumers who patronize more efficient producers.

Adam Smith raised an important question, but he could not imagine that, thanks to the fast economic growth that was to become typical of free societies, few workers would remain stuck in mindless manufacturing. In a modern developed economy, most jobs require some knowledge, thinking, and initiative. In manufacturing, which accounts for less than 10% of employment in America (like in most rich countries), the most repetitive tasks are done by machines. We in the rich world should be happy to be there. And our governments should not fall into economically illiterate and morally reprehensible attempts to prevent poorer countries from rising to our level of development. (Recall that in China, GDP per capita is less than one-third the American level; Vietnam is at 14%—according to data from the 2023 Maddison Project database.)

The most important questions remain to be asked: Who should be producing which goods and services, how, and where? Economic theory and history strongly suggest two alternative answers. The first is to leave the decisions to some authority: the tribe, the council of elders, rationally ignorant voters, politicians, the king, the strongman, or the planning bureau. The second way is to rely on consumer sovereignty, free enterprise, competition, and laissez-faire: letting each individual and each voluntary association (including corporations) decide what to do, and with whom to trade and at what terms.

******************************

Mindless manufacturing

econlib