📕 😂 👍🏻

A couple of years ago, I frequently found myself driving past a roadside ice cream stand under construction. For weeks, the roof of this stand, a gigantic white swirl of fiberglass soft serve, sat on the ground next to the structure, waiting to be lowered onto the finished, cone-shaped building with a crane. I know what it was supposed to represent, but every time I glimpsed it, my instinctive first thought was There’s a giant poop emoji.

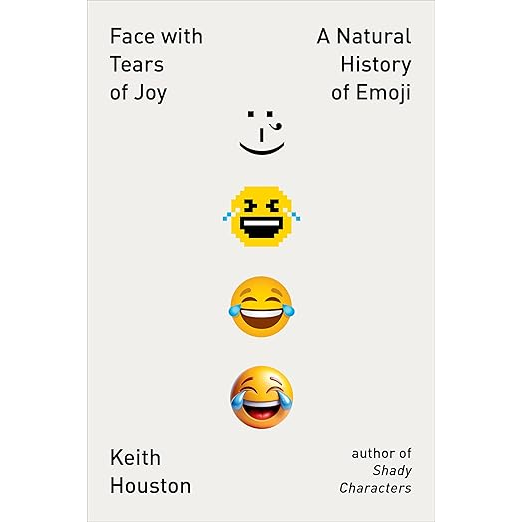

Keith Houston’s history of emoji, Face With Tears of Joy, argues that emoji have “become so ubiquitous in our writing, so quotidian, that we should be talking about them in the same breath as grammar or punctuation.” I don’t know about grammar, which seems as fundamental to language, spoken and written, as words themselves. But punctuation? Absolutely. As Houston’s breezy, witty blend of pop culture and tech history ponders exactly what emoji are—symbols? Words? Pictographs? A script? A language?—his assertion that these little images have become an inextricable part of our culture, and even perhaps of our unconscious minds, feels credible, that giant poop emoji by the highway being a case in point.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Face With Tears of Joy delves way back into the history of written language, which began with pictures of actual objects—ideograms—then evolved into symbols for spoken sounds. Cuneiform, hieroglyphics, and Chinese characters started out this way, so, Houston writes, it is “tempting to imagine that emoji, too, might one day become a true script through a similar mechanism.” But projects like a gibberishy 2009 “translation” of Moby-Dick into emojis served only to demonstrate how unlikely that is. Emoji don’t, after all, have any meaningful relationship to spoken language, and the languages emoji users speak already have their own written forms. Emoji are entirely a phenomenon of text-based communication.

Houston traces the emergence of emoji back to their motherland in Japan, where devices as primitive as pagers supported little pixelated images that users found delightful. (He uses the term emoji both for a singular glyph and for the whole lexicon of images, in deference to these Japanese origins.) There’s some debate over who exactly created the first emoji, but initially the credit went to an engineer named Shigetaka Kurita, who created a font made of symbols for cellphones in the late ’90s. From the start, emoji reflected the interests of their creators. According to Houston, Kurita “added symbols for hands making ‘rock,’ ‘paper,’ and ‘scissors’ gestures because he thought they might be useful in mobile games,” and in addition to the more generic emoji of a sedan, he included one of an SUV, “because Kurita drove one whenever he went snowboarding.”

Emoji caught on in the West in the 2010s, when Apple made colorful, detailed versions available on the iPhone. Google had included some pictographs it called “goomoji” in Gmail during the 2000s and initiated the important step of petitioning an organization called the Unicode Consortium to oversee the standardized coding of emoji, but it took ubiquitous, high-resolution texting to take emoji mainstream outside Japan. The parts of Face With Tears of Joy leading up to this introduction make for a nostalgic jaunt for early adopters, with stops at such evocative innovations as the Zapf Dingbats font in the first Macintosh computers to once commonplace emoticons.

Houston doesn’t make enough of emoticons, the first of which was proposed in 1982 by the computer scientist Scott E. Fahlman on the electronic bulletin board of Carnegie Mellon University. The bulletin board’s text-only discussion forum, one of the main forms of online conversation at the time, had a problem: It wasn’t always obvious when someone was joking. Fahlman proposed that such posts include a “marker” made of a colon, a dash, and a closing parenthesis (a character sequence I now can’t type without my word processing program transforming it into a smiley face).

As primitive as emoticons were, they addressed a big issue in these emerging forms of communication. Online posts were informal, like conversation, but lacking the cues in spoken language that are not words: tone of voice, facial expressions, hand gestures, laughter. This lack of contextual flavoring is often blamed for the way online interactions can so easily blow up into misunderstandings and feuds. Some very accomplished writers might be able to convey everything they want to say in words alone, but with the advent of the internet, countless people with basic writing skills were suddenly plunged into often sensitive exchanges without the aid of the extratextual qualifiers that make personal interaction so much more clear for most of us. So they fashioned facial expressions out of punctuation marks to make up the difference.

Faces remain among the most commonly used emoji, lending credence to a 2019 paper by linguists Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne, “Emoji as Digital Gestures,” that, Houston reports, “makes a convincing case that emoji act as the body language of the web.” The popular emoji that aren’t faces—heart, folded hands, waving hand, side-eyes—all stand in for gestures or expressions of feeling that aren’t always easy to convey in text alone. This is the core utility of emoji, the part worth a thousand words—words that many of us aren’t able to command effectively even if we wanted to. Without hearts and smiley faces, emoji would probably have remained a seldom-used curiosity, like the pointing hands and snowflakes of Zapf Dingbats.

Instead, emoji blew up right around 2011, and one of the primary pleasures of Face With Tears of Joy is the opportunity it offers to revisit the online culture of the 2010s, when the internet still felt fun. Yes, people protested the monochromatic skin tones of the first sets of emoji depicting humans and lobbied for a greater variety of hair colors and skin tones, as well as the option to depict same-sex couples and women in the trappings of professions other than dancing girl. And yes, this sometimes resulted in cranky peanut-gallery tweets, such as “I’ve been waiting forever for the ginger emoji and THIS is it?? Uh, hello?”—documented in the invaluable online resource Emojipedia. But these disputes lacked the entrenched bitterness of today’s internet culture, and for much of the decade, each new tranche of emoji was heralded by amusing press coverage and silly controversies over such matters as where Google should place the slice of cheese in the cheeseburger glyph. (It was initially depicted under the patty, which is obviously very wrong.)

In the 2010s, emoji provided a seemingly inexhaustible source of clever light news and watercooler chitchat about which glyphs had won the approval of the Unicode Consortium and the inventive ways people had found to deploy them. The expanded variety of available images gave users the opportunity to turn the eggplant and peach emoji into synonyms for body parts and the nail polish emoji into a symbol of insouciance. As Houston chronicles, dating sites and the scholars who studied them correlated emoji usage to frequency of sexual encounters (more frequent emoji users had more sex), while noting that emoji in a profile made the owner seem less intelligent to other members of the service.

An Australian foreign minister responded to an interview using only emoji. President Barack Obama thanked Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe during a state visit for his nation’s many contributions to international culture “and, of course, emoji.” BuzzFeed created an election night tracker for the 2018 midterms that allowed users to respond to the news feed with emoji. In 2015 the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary chose the emoji after which Houston’s book is titled as its Word of the Year. The catnip of generational comparison has led to articles observing that the face with tears of joy emoji is associated with millennial laughter, while members of Gen Z use the skull emoji to indicate they’ve found something lethally funny. Anyone who’s spent much time in the comments sections of social media will also recognize that in the past five years, “face with tears of joy” has taken on an edgier connotation, as it’s now often used to signal derision at the statements of political opponents. Nothing today, it seems, can long remain free from the trolls.

Emoji still provide slivers of delight. A friend and I concluded a recent text exchange arranging a summer visit with 🌳 and 🌞, as a reminder that even in difficult times, we can find solace in nature. But the problem that emoji stepped up to address—the lack of nonverbal modifiers in text-based communication—may be creeping toward irrelevance. As social media shifts from text posts to short videos, we usually don’t need a yellow smiley face to tell us when a speaker is laughing or being sarcastic. (Granted, emoji still come in handy when you want to post a comment to the video.) Perhaps the day will come when people driving past that ice cream stand will think only of creamy frozen desserts. But not me—at least not yet.

Slate