What Was It Like to Be Edited by <em>Toni Morrison</em>?

I first interviewed Toni Morrison about her work as a book editor in September 2005, in her office at Princeton. Though our meeting was scheduled for late afternoon, I took an early train from Washington to make sure I could situate myself in West College—which would be renamed Morrison Hall in 2017—while I rehearsed my carefully crafted questions. I was struck by the quiet gravity of the building and its hallways: sunlight slanting through stately windows, the scent of old books and weathered wood lingering in the air. The fact that I was about to sit across from a literary giant—celebrated worldwide for her novels yet virtually unknown for her groundbreaking work as an editor at Random House—was not lost on me.

My anxiousness reminded me that I had often wondered what it must have been like for authors to have the Toni Morrison as their editor. When the writer John A. McCluskey Jr. first met Morrison in 1971, she had published only The Bluest Eye. McCluskey, not yet 30 years old, saw her not as the Pulitzer Prize–winning Nobel laureate she would become, but as a fellow Ohio writer looking to make her mark as an editor. She was also, he discovered two years later, the kind of person who made a fuss when she learned that McCluskey’s wife and son were in the car waiting while they had their first author-editor meeting at the Random House offices on East 50th Street to discuss his first novel, Look What They Done to My Song. Whatever else was on her schedule would have to wait. She wanted to greet Audrey and Malik. It was the least she could do since they had joined McCluskey for the drive from the Midwest to Manhattan.

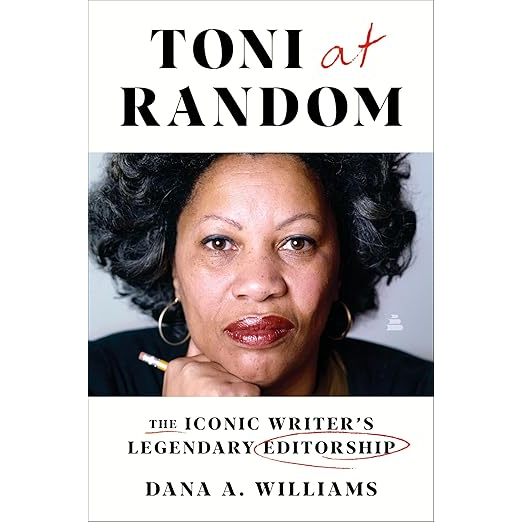

In my book Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, I tell the story of Morrison’s 12 highly productive years at Random House, from 1971 to 1983. Most of Morrison’s influential work as an editor was, in fact, completed before she achieved fame as a literary giant. For the writers she edited, she was not a celebrity but the person who could help them produce a better book. They admired her skills as an editor and appreciated the consistency of her deep engagement with their manuscripts. By the time she published Song of Solomon, in 1977, it was impossible to ignore her growing importance as a writer. But even then, she made a point to leverage her public persona to promote the books she helped bring into print.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Once I joined Morrison in her office, which was furnished tastefully with modest art, a large, stately desk, and a bevy of neatly arranged books on tall shelves, her gift as a storyteller revealed itself. As she spoke—measured, reflective, and occasionally animated by some memory that rushed to the fore of her mind—I followed the rhythm of her insights. I conceded that it would be her preoccupations, not my prepared questions, that would guide our time together. At one point, she reached for Contemporary African Literature, an anthology compiled by Edris Makward and Leslie Lacy. Published in 1972, it was the first book she edited, and it was clear she remained very proud of her work.

“Isn’t this book stunning? It’s just beautiful,” she said. The cover featured a striking silhouette of an African profile rendered entirely in black, set against a deep purple background.

When Ms. Morrison asked if I had seen the book before, I admitted that I had not. She handed it to me for what I considered to be an opportunity for redemption. If I could offer a close reading of the image, that might compensate for my embarrassment.

The profile was ungendered, I suggested. “Intentional,” she announced. “Gender could be such a silly distraction.” I pointed out the necklaces, which reinforced a sense of tradition, heritage, and pride in African culture. Yes. Was the profile of an African from the Maasai people, known for their elongated earlobes? Right again, she affirmed, my confidence building with each knowing nod. What was in the African’s earlobe? Was it a cigar tube case, a relic of colonialism; or was it another artifact meant to symbolize a scroll, quietly affirming the fact that African writing systems predated colonialism? As I marveled at the image, agreeing that the cover was as handsome as she had initially suggested and noting that it had layers upon layers, the point had been made: Every detail mattered.

This unyielding attention to detail was among the most enduring features of her editorship and accounted for so much of her success at Random House. Not long after moving to Manhattan from Syracuse—where she’d worked at the L.W. Singer Company, a small press that specialized in textbooks—she became the lone Black editor at prestigious Random House. This single mother of two could not afford missteps. She intended to excel both as a writer and as an editor. From a book’s cover and every sentence within it to the book’s promotional strategy, she left nothing to chance.

She worked closely, for example, with the jacket designer for From Memphis & Peking, a poetry collection by sculptor-turned-poet Barbara Chase-Riboud. When Chase-Riboud expressed concern about an early draft of the book’s layout Morrison shared, Morrison noted that she and the designer had talked about every detail of the book. “I never worked with a designer who was such a perfectionist,” she wrote. “You are not the French lady poet—he is!” Morrison knew that Chase-Riboud’s first literary achievement would need to be rendered as artistically as possible, as a way of introducing her new genre to her existing visual-art audience.

One of the things that excited Morrison the most about joining the team at Random House was the opportunity she would have to acquire books that would document Black life and culture that reflected Black people’s interior lives, not simply books filled with public outcry against, and resistance to, racial oppression. The book that epitomized this goal of featuring Black life and culture with limited regard for whiteness was 1974’s The Black Book. Importantly, too, it put to bed the misconception that Black people did not buy books (or that white people would not buy books that were distinctly Black). And it made the point that everyday Black life was remarkable. “Bringing that book in the world didn’t even feel like work,” I remember her telling me. “It was more than work. It was pure joy.”

For many of the authors she edited, Morrison extended her work well beyond a book’s prepublication needs. When the New York Times published Glyn Daniel’s ill-informed review of Ivan Van Sertima’s 1977 book They Came Before Columbus, Van Sertima drafted a stinging response, even accusing Daniel of not having actually read the book. “This learned gentleman cites Men Across the Sea and Quest for America as ‘fundamental’ works in the area of pre-Columbian contacts,” Van Sertima wrote. “According to him, I have not read these books. Had he studied my work … he would have noticed that I have made nearly 100 references to these texts.”

Morrison read Van Sertima’s two-page letter with glee. “Your reply to the Times is fantastic!” she wrote to her author. “I called Mel and told him I want every world of it printed.” She had no problem insisting to her friend Mel Watkins, the first Black editor at the Times’ Sunday Book Review, that Van Sertima be given the opportunity to respond in print to Daniel’s dismissal of the book. There was seldom a clear starting or stopping point when it came to her willingness to advocate for a book she edited and admired.

One might think Morrison’s growing success as a novelist translated effortlessly into success in editing novels by writers she admired. It did not. “It wasn’t easy getting those first novels published,” she admitted to me. The novels by Black authors who seemed to get the most attention, she saw, fell along two poles: the ones she referred to as “Fuck whitey” or “I’m going to fix you, whitey” books on the one hand, and “Let’s all live together in harmony” books on the other. She had little interest in either approach. Those books were ultimately about white people. And what she wanted to publish, both as a writer and as an editor, were books that talked to Black people.

When the poet Michael Harper sent her boxes of stories by his student Gayl Jones, Morrison got her first opportunity to work on the kind of fiction she found most appealing. One of the first stories she read was about a character named Ursa. Morrison wrote to Jones (who, due to shyness, preferred letters to calls and in-person visits), asking a series of questions about that story; those questions led Jones to expand the story into what eventually became the novel Corregidora. An editor at Holt, Rinehart—where Morrison had published The Bluest Eye—sent her a novel he thought was interesting but didn’t quite understand. That was Leon Forrest’s first novel, There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden. These books talked pointedly to and about Black people. White people could read them too, but they would not be the center of the books’ attention—nor did Morrison consider them the books’ primary audience.

In nonfiction, Morrison was drawn to provocative thinkers whose ideas might move the needle on race in America. But she also demanded the books be as good as she thought they could be. In October 1971, Random House editor-in-chief Jim Silberman invited her to consider working with imprisoned Black Panther Party founder Huey P. Newton. She agreed to edit what would become To Die for the People only if she had free rein to do what was needed to ensure the book was done well. Though many of the essays in the book had previously been published, she insisted upon reediting the book in earnest. She shared her recommendations with Silberman after a quick reading:

Delete some of the truly weak essays, edit all. Don’t know if those that were printed can be re-worked but that should be a condition. … I think the Panthers and their prose should be given the benefit of editing and thus be shown in its best light. The job would not be overwhelming.

In the end, she was satisfied with what they were able to accomplish. And she did not hesitate to share that sentiment with Newton, to whom by then she referred casually as “Huey.” “My feelings about the book, which I have never communicated to you,” she wrote, “are that it is one you should be very proud of. The most striking feature is its reflection of the many facets and strengths of the party. … All in all it is truly a remarkable collection and should do a great deal to educate the public about his country, this world as well as the Party.”

Around the same time she began working with Newton’s manuscript, she agreed to talk with Yale Law professor Boris Bittker, who was working on a book that examined the problem of group compensation for slave labor. Notably, the book did not actually make the case for extending reparations to Black people; it simply addressed the legality and plausibility of the proposition. So when Morrison suggested the title The Case for Black Reparations, Bittker resisted. In his view, the title gave a “misleading impression of the overall tenor of the book.” He suggested instead “Black Reparations: A Second ‘American Dilemma.’ ”

Morrison presented the book at the presales conference with the title Bittker proposed, but the editor in chief, sales manager, and publicity director all suggested dropping the “American Dilemma” subtitle, Morrison told the author, even without her expressing her reservations. It took some convincing, but she did get Bittker to trust her judgment about reaching a broader audience. She insisted that the title did important work in getting the potential buyer to pick up the book. And his goal, after all, she reminded him, was to take the reparations conversation out of its ghetto and bring it into the mainstream. Her job as editor was to secure as broad of an audience as possible for this well-researched, “radical” idea.

Sometimes an editor’s job isn’t even about overseeing the content of a book. It’s about staying the course with an author, even when the book hasn’t been written yet. It was Morrison who came to the defense of Muhammad Ali and Ali’s collaborator Richard Durham when The Greatest was continually delayed. Ali had signed the contract for the book in 1970, after his boxing license was suspended. Once the Supreme Court overturned his conviction for draft evasion and his license was restored, though, Ali shifted his focus from writing an autobiography and toward regaining his title. Morrison advocated inside Random House and worked closely with Durham to keep the contract alive and, ultimately, to complete the manuscript. As late as May 1974, Morrison lamented that there was no coherent manuscript despite her best efforts, so it was not surprising that no one from Random House took Ali up on the offer to attend the October 1974 fight in Zaire against George Foreman that promoters dubbed the “Rumble in the Jungle.” One of Ali’s first, hurried telegrams after winning the fight was to his publisher. He bragged: “This s the last chapter needed for my tory Now I feel free to finish with the ending I want.”

Morrison immediately began to assemble the pages they had and to chart the status based on the outline of the book as she imagined it once it was complete. No chapter could be marked complete. Each was labeled either in draft, scattered, more to come, or no material. Some of the sections she labeled rough did have transcripts from tapes that she could at least use, if it came to that. She and Durham went to work, spending all of May 1975 together in New York getting the manuscript in order. Once they finally produced a full draft, she suggested a print run of 100,000—the largest on the firm’s list that year. The publication and enormous success of The Greatest, almost six years after Random House’s standing-room-only press conference announcing the contract, was almost as much her achievement as it was Ali’s.

During that meeting back in 2005, Morrison invited me to examine every feature on the cover of the first book she edited—the color, the typeface, the image and its nuances—as if the entire spirit of her editorial work were reflected in those details. The choices she made—about covers, about titles, about revisions and missed deadlines, about audiences—gave the books she edited the same kind of authority I saw in her office. Her unwavering commitment to shoring up the integrity of a book at every stage solidified her legacy as an editor who could turn talent, hers and that of the authors she published, into cultural and literary power.

Slate