The risks of the country sinking into a constituent assembly

The proposal to convene a national constituent assembly in Colombia has reappeared in the political debate as an alternative to a referendum and, in general, as a way to overcome the obstacles that, in the current government's view, are posed by the existing institutional framework.

President Gustavo Petro and Justice Minister Eduardo Montealegre have indicated that Congress has blocked essential structural reforms, and they argue that this blockage—along with procedural issues—could justify resorting to the constituent power to overcome legislative instability.

President Petro spoke again about the constituent assembly after signing the decree for the referendum. Photo: Joel Gonzalez. Presidency

Montealegre had already stated in a press release in May 2024 that the constituent assembly is not only legitimate, but a political obligation derived from the 2016 peace agreement, as that treaty has "constitutional status" and the Executive branch has the authority to enforce it.

However, this proposal has sparked an intense legal and political debate that has exacerbated polarization and raised questions about institutional limits and the preservation of the rule of law. For these reasons, it is essential to analyze its legal viability and the procedures necessary to implement it, as well as to assess the political significance of a constituent assembly, since the process requires a balance of political legitimacy and compliance with the current constitutional framework.

The requirements In the context of this debate, several options have been raised for convening a constituent assembly, including the possibility of doing so through a popular referendum , without the need for a prior law, or by direct citizen initiative through the collection of signatures, as permitted by Articles 3 and 103 of the Constitution.

President Gustavo Petro Photo: EL TIEMPO Archive

However, these alternatives have been the subject of legal challenges and could be declared unconstitutional , given that Article 376 establishes the approval of a law through Congress as the only legitimate means: "By law approved by Congress, by a majority of the members of both chambers, the people may be summoned through popular vote to decide whether to convene a constituent assembly for the purpose of reforming the Constitution."

This exceptional mechanism allows for the replacement or substantial reform of the political charter, but its activation is subject to strict conditions, both legally and politically, as established in articles 58-63 of Law 134 of 1994 and article 20, paragraph e of Law 1757 of 2015. According to these rules, the steps to follow would be:

Approval of a convening law: Congress must pass a law that clearly establishes the motivation and scope of the constitutional reform, the number of members who will comprise the assembly, the rules for their election, the timeframe within which it must operate, and the mechanism for submitting the convening to a referendum. This law requires an absolute majority of both chambers , that is, at least 54 senators and 86 representatives.

Senate Plenary Session. Photo: César Melgarejo/El Tiempo

Constitutional Review: Before its enactment, the law intended to convene a constituent assembly must be reviewed by the Constitutional Court , pursuant to Article 241 of the Constitution, to ensure that it respects democratic principles, does not violate fundamental rights, and complies with the substantive and procedural limits established by the Constitution.

Approval by popular vote: Once the Constitutional Court approves the convening law, a popular vote must be held, in which citizens will have the opportunity to decide whether to accept the formation of a constituent assembly . For the result to be binding, it must exceed one-third of the electorate.

The convening of the constituent assembly will be approved when at least one-third of the members of the electoral roll vote in favor. Based on the current roll, at least 13,696,612 votes in favor would be needed.

Election of the members of the constituent assembly: If the assembly is approved, the election of its members will be held within two to six months.

Once the assembly is elected, during the established period of its functioning, it will have the power to deliberate and approve provisions related to the matters within its jurisdiction.

In this regard, it is important to emphasize that, under Colombian law, although the Constituent Assembly may have a broad mandate, it cannot go beyond that mandate. A Constituent Assembly cannot extend its mandate or act as an unlimited power unless expressly authorized by the people.

President Gustavo Petro celebrated the approval of the reform in Congress. Photo: Ovidio Gonzalez. Presidency

In various rulings, such as C-141 of 2010, the Constitutional Court has emphasized that the derived constituent power is subject to democratic legality and must strictly adhere to the procedures established by the Constitution.

However, although the constitutional and legal framework allows for the convening of a constituent assembly, it is crucial to fully understand the scope and political implications of this tool before embarking on a process of such magnitude.

The political meaning Constituent assemblies represent one of the most powerful mechanisms in contemporary constitutional law: they allow the original constituent power—popular sovereignty—to be directly expressed in order to transform or replace a country's institutional framework, resulting in a profound reconfiguration of the social pact, with legal, symbolic, and political implications.

NATIONAL CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY Photo: El Tiempo Archive

This process has the potential to relegitimize political systems marked by mistrust, corruption, or exclusion by offering a transparent, participatory, and pluralistic space. Furthermore, it can consolidate a new national consensus on the purposes of the state, the organization of power, and fundamental rights, which fosters social reconciliation.

In symbolic terms, a constituent assembly implies a break with the past and the construction of a new national narrative, as demonstrated by the cases of South Africa in 1996 and Bolivia in 2009, and even Colombia with the 1991 Constitution. It also acts as an instrument of social mobilization, promoting public deliberation and strengthening civic culture in traditionally marginalized sectors.

Institutional uncertainty during the process can generate legal loopholes and disputes over normative supremacy.

However, while it can be a transformative mechanism, it also carries significant risks because its convening is neither neutral nor mechanically technical.

While it can be a way to relieve institutional rigidity, a way to deepen democracy and rebuild the social contract, it can also be used as an instrument to concentrate power, erode constitutional guarantees, or legitimize personal projects.

Institutional uncertainty during the process can generate legal loopholes and disputes over normative supremacy, while its potential capture by authoritarian elites or majorities can endanger democracy and increase the risk of authoritarian regimes masquerading as direct participation.

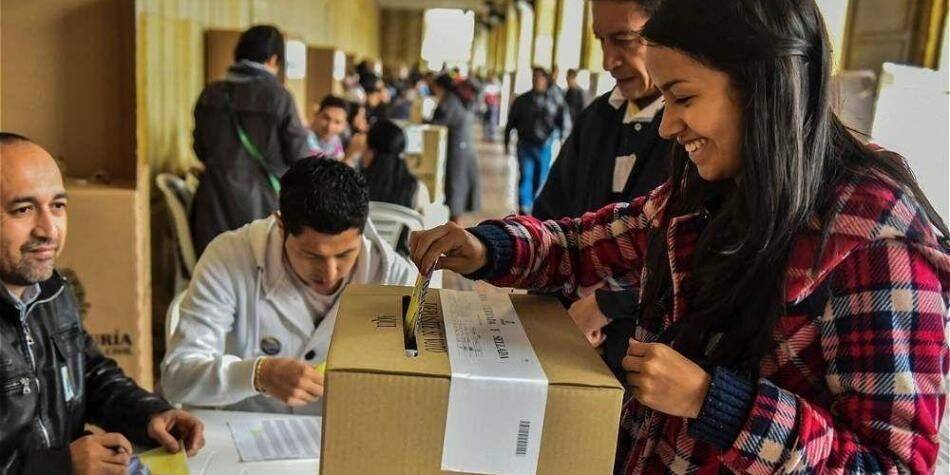

Voting. Photo: Luis Acosta. AFP

Furthermore, there is a potential for the weakening of existing constitutional guarantees, especially fundamental rights and oversight mechanisms, if clear limits are not established.

The case of Chile's Constituent Assembly (2021-2022) exemplifies both the achievements and the limitations of convening a constituent assembly. With gender parity and seats reserved for indigenous peoples, the convention was the first of its kind in the world, but its proposal was ultimately rejected by 62 percent of the electorate in September 2022, highlighting a gap between the deliberative ideal and public perception, as well as the risk that the proposals may prove too radical or impragmatic.

While constituent assemblies offer a unique opportunity to recast the social contract with inclusive participation, they also carry risks of polarization , rejection, and weakening social cohesion if the institutional design and the degree of deliberation are not well balanced.

Is it convenient now? In the particular case of Colombia, convening a constituent assembly could pose a risk given the country's level of political polarization. It could exacerbate social and political divisions and favor partial interests rather than a national consensus.

Silent March in Bogotá Photo: Néstor Gómez

The push for a constituent assembly as a solution to the political frustration with Congress can be interpreted as a way of circumventing democratic checks and balances, weakening the legitimacy of institutions that must be reformed from within. Critics and legal experts have pointed out that it could represent an "assault" on the separation of powers, with the risk of leading to a "self-coup."

On the other hand, organizations such as Dejusticia emphasize that the proposed reforms are already viable within the current constitutional framework, and warn of the dangers of taking a path that, rather than strengthening democracy, could fracture it.

Indeed, the 1991 Constitution, considered one of the most advanced in Latin America, establishes fundamental, social, and collective rights, in addition to guaranteeing mechanisms such as citizen protection and participation. It also established reform mechanisms that allow for its gradual adaptation, without the need to completely replace it.

It has been amended more than fifty times to address key issues such as justice, balance of power, and the peace agreement. Therefore, the necessary changes in areas such as social justice, agrarian reform, and the democratization of power can be achieved within this framework , provided there is political will and institutional capacity.

The underlying problem in Colombia has not been the lack of progressive laws, but rather their weak implementation. Many of the promises of the 1991 Constitution—such as the right to health care, free education, territorial autonomy, recognition of ethnic groups, and, more recently, the commitments of the peace agreement—have been ignored, defunded, or sabotaged by political, economic, and bureaucratic interests.

In this context, promoting a new constitution could distract from the real challenge, which is to consolidate a capable, fair, and effective state that guarantees the rights already recognized. Furthermore, launching a constitutional process without addressing the structural implementation gaps could result in a new unfulfilled charter of intent, which would further fuel citizen disillusionment and institutional disaffection.

Silent march in Bolívar Square. Photo: Néstor Gómez. EL TIEMPO

In conclusion, convening a constituent assembly in Colombia, far from being the solution to the country's structural problems, could become a costly, risky, and destabilizing exercise if the minimum conditions of consensus and institutional maturity are not met.

The 1991 Constitution is not the obstacle: the real challenge is enforcing it, deepening democracy through its effective implementation, and strengthening the state's capacity to guarantee rights and build lasting peace. Rather than reestablishing the legal system, Colombia needs to reaffirm its commitment to the social rule of law enshrined in its current Constitution.

MARCELA ANZOLA* - PUBLIC REASON**

(*) Lawyer from the Externado University of Colombia, Ph. D. in Political Studies from the Externado University of Colombia, independent consultant.

(**) Razón Pública is a non-profit think tank that aims to ensure that the best analysts have greater influence on decision-making in Colombia.

eltiempo