"Jaws" Turns 50: The Story of the First Shark Blockbuster... Without a Shark

Fifty years ago today, on Friday, June 20, 1975, Jaws was released in American cinemas . The film, directed by a very young Steven Spielberg, tells the story of the hunt for a human-eating great white shark in a small seaside resort on the east coast of the United States.

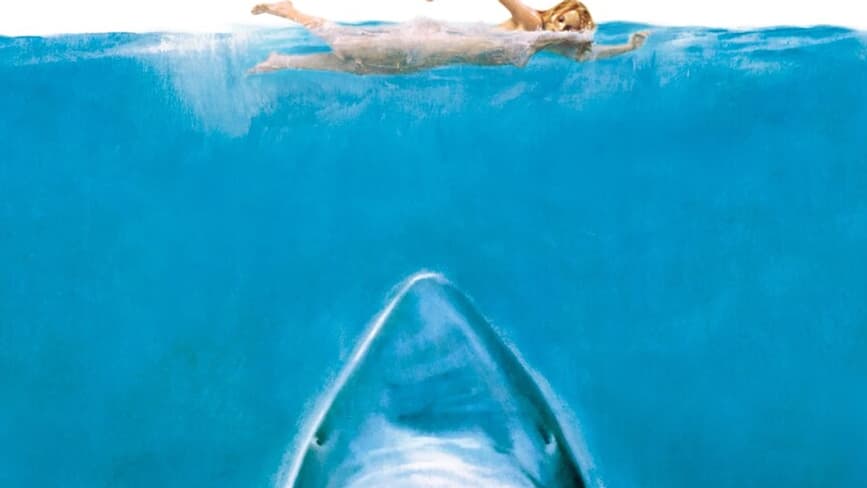

What was supposed to be a B-movie would become an immediate and global success, to the point of becoming a cult classic. And contrary to what the film's poster suggests, depicting a colossal shark with its mouth open, ready to devour a swimmer, the shark—the film's main character—is almost entirely absent. This didn't stop Jaws from terrorizing entire generations of swimmers.

"The film is all the more powerful because the shark is invisible," Olivier Bonnard, co-director with Antoine Coursat of the documentary Jaws, a huge success , broadcast on Arte, analyses for BFMTV.com.

The shark claims its first victim in the film's opening frames. But not a single tooth, not a single fin, appears on screen. "We only hear this music that will represent and embody the shark," the documentary filmmaker points out. A now-iconic music by John Williams: two notes, E and F. A motif that repeats, accelerates, and becomes the signature of the film. And of the shark.

"From the opening scene, the viewer will associate the sudden burst of this music with the shark," continues Olivier Bonnard. "The music works viscerally; it's like an alarm signal. It embodies this invisible threat."

During the second shark attack: still not a single shark in the water. The director only shows the pool of blood left after a bather was devoured and the shredded remains of her air mattress.

"In terms of fear, it's much more effective to show the monster's damage than the monster itself," says the documentary maker.

In the next attack, the monster's strength is demonstrated: a wooden pontoon is ripped off by this powerful, yet still invisible, beast. The pontoon is first dragged into the ocean, then turns around, suggesting the threat of the shark returning to attack fishermen who have fallen into the water. "It's a striking demonstration that the less we see, the more afraid we are," continues Olivier Bonnard.

"It is the power of suggestion and off-screen that gives free rein to the imagination. No image, however realistic, even in 3D, can compete with mental images."

It takes an hour to see a fin, then the underwater silhouette of the monster circling its next prey. Twenty minutes later, we see the shark's sharp teeth, with the famous line from the local police chief, played by Roy Scheider: "You're gonna need a bigger boat."

" Jaws is a really well-executed striptease," sums up Olivier Bonnard.

"Spielberg makes the shark appear very gradually. First a piece of fin, then a little more, until you see the whole thing. It's a lesson in cinema."

The film would also pioneer a new cinematic genre: "sharksploitation," a subgenre of exploitation films featuring sharks or shark attacks. The latest is Under the Seine, which features a female mako shark threatening the triathlon world championships in the Seine River in Paris. It was a hit last summer on Netflix and the first French production to surpass 100 million views.

Yet, originally, the shark should have been much more present in Jaws. But when Steven Spielberg started filming, neither the mechanical shark nor the script were finished - the film and the dialogue were written the day before for the next day.

And when Bruce—the nickname given to the fake shark—is finally ready, disaster strikes: he sinks, and the salt water fries the electronic circuits. Bruce weighs a ton and a half and was tested in fresh water; however, filming takes place in the open ocean for greater realism. None of the various shark models—designed by the creator of the giant octopus in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea— which measured more than eight meters long will do the trick.

Steven Spielberg had to make a shark movie without a shark, or at least without the animated shark that was planned. So he switched his handheld camera and shot from a low angle, adopting the shark's point of view.

"We don't really know how much of this is legend and how much is true. What is certain is that if the shark had worked, we would have seen it more. But if the film has stood the test of time so well, it's also because we don't see the shark very often."

Steven Spielberg himself admitted this in the documentary Music by John Williams: "My shark wasn't working. And I had no idea that John (Williams, the composer, editor's note) was going to give me a shark that worked thanks to music. His musical shark was much more effective than my mechanical shark."

Within days, the $12 million budget was recouped. The following year, the film won three Oscars (editing, music, and sound). This success would spark a saga. Three more films—without Steven Spielberg—would follow, but with mixed commercial and critical success.

Jaws will remain the first blockbuster in cinematic history and pave the way for franchises. It also launched the career of Steven Spielberg, who was previously little known to the general public, and allowed him to make cinematic history.

"There aren't many films that remain as powerful fifty years later."

BFM TV