A Flashy New Show About 1930s Britain Has Messy Aristocrats, Champagne Bashes, and a Woman Stalking Hitler. Did All That Actually Happen?

This article contains spoilers for Outrageous.

If you didn't know BritBox's new limited series Outrageous was based on the true story of the Mitford sisters—women who were the Kardashians of their day, if the Kardashians were famous for aristocratic eccentricity, literary talent, and political views running the gamut from devoted communism to ardent Nazism (but equally given to squabbling among themselves)—you might think it was a version of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice , transported to the 1930s. There's a family who are part of the genteel landed gentry, with excellent connections but struggling to afford to remain in their social circle, and with several daughters to marry off (preferably to rich husbands with nice houses). One sister has a gimlet eye for hypocrisy and a way with witty repartee, another is an admired beauty who attracts an extremely eligible suitor, and the third is not worried about social norms and impetuously follows her heart without parental permission, causing a huge scandal.

But there is a major difference. While the politics of the larger world rarely intrude on the life of the Bennets (the family at the center of P&P ), the Mitfords came of age in a period of economic instability and political extremism following the Wall Street crash of 1929, when the Have-Nots were really up against it (2 million were unemployed in Britain alone in 1932, before any kind of social safety net existed) and understandably resentful. Two political movements in particular exploited this widespread discontent: the communists from the left, promising to redistribute capital; and the fascists from the right, promising to entrench capital in the hands of the rich even more but also to kick out the minorities and leftists who could conveniently be blamed as the true source of any economic woes—demonstrating the truth of the adage that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Meanwhile, as the show depicts, the Haves were blithely enjoying frequent Champagne-fueled parties in elegant private homes and swanky nightclubs. While some of them—including Nancy, the eldest sister, who, as the author of comic novels satirizing her own social class (and indeed her immediate family)—were disturbed by the wide gap between the classes, others (like most of the other Mitfords) drifted in the other direction, believing that at least the fascists would keep communists and socialists at bay, enabling them to retain some grip on financial security.

While the tone of the show is largely light and breezy, showrunner Sarah Williams leans into the contemporary relevance of families balancing ties of affection with diametrically opposed political views. (A Christmas lunch where everyone is struggling not to rise to one daughter's blatantly racist observations is a familiar feature of the modern holiday season.) A combination of privilege, sophistication, and behavior that ranged from unconventional to borderline lunacy has kept the family in the spotlight more than they would have liked since the 1920s. We take a look at what is fact (however unbelievable) and what has been invented in Outrageous .

In the show, the girls' father, the crusty, irascible Lord Redesdale (known to his family as “Farve”), refuses point-blank when the intellectually curious Jessica, a voracious reader and something of an early “social justice warrior,” asks to go to a local school because she aspires to go on to college. “Girls don’t need school,” he thunders.

This is based in fact. Nancy Although briefly attended a local school in West London, after the family moved to Oxfordshire the girls were largely homeschooled by their mother (aka “Muv”) and various governesses, interspersed with spells of taking lessons at neighbors' homes with similarly upper-class girls. In fairness, this attitude—a holdover from Victorian times when aristocratic young ladies were educated at home—was not so unusual among the aristocracy even by the 1920s. After all, although a decade younger, Elizabeth and Margaret, the two royal princesses, never went to school with other children but were tutored at home. Meanwhile, the lone male Mitford child, Tom, was sent off to Eton.

The girls received basic instruction in reading, math, and French, but there were holes left in the curriculum (indeed, a better grasp of history might have made them more resistant to ideologues). Nevertheless, four of them (Diana, Deborah, Jessica, and Nancy) became creditable authors, with the latter two acclaimed. Their isolation from wider society in their formative years led to their developing a private language, esoteric family games, and an impenetrable thicket of nicknames. (This was a tendency not limited to the Mitfords, as a quick glance at any PG Wodehouse book will confirm. The British upper class loved nicknames because they left the uninitiated in the dark while confirming the bonds of familiarity among the in-group.)

Favre's attitude may have been a reflection of his personal circumstances as much as a genuine belief that education was wasted on the female brain. For one thing, he was perennially short of money and may have been inclined to sixteen on any excuse to save on school fees. For another, his own experience of education was not a happy one, since he much preferred riding horses to reading; he later declared he had read only one book in his life— White Fang , Jack London's novel of life in the Yukon, which at least features several dogs.

In the series, Unity Mitford is introduced to fascist ideas by her older sister Diana, who has fallen in love with Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists. Unity's combination of strong passions, limited horizons, and need for attention make her an easy target for radicalization, and she has developed a mad crush on Adolf Hitler. In 1934, she persuaded her parents to send her to a finishing school in Munich to perfect her German. Learning that Hitler and his entourage frequently have lunch at the same restaurant every week, she lunches there every day in the hope of running into him. Eventually Hitler notices her and invites her to join his private table in the back.

This is largely true. Unity did have lunch every day at the Osteria Bavaria until she was able to come to Hitler's attention. However, she was not nearly as attractive as Shannon Watson, the actress who portrayed her. Though she shared Diana's uber-Aryan blond hair and cornflower-blue eyes, she lacked her sister's glacial beauty, and, at nearly 6 feet tall, was big-boned and rather galumphing.

She was also distinctly odd even without the Hitler adoration. The show depicts her bringing her beloved pet rat to a debutante dance stashed in her handbag. The real Unity not only did this but would occasionally adorn herself with Enid, her grass snake, worn as a necklace. However, she was also young, an English aristocrat, and adoring, and appealed to Hitler's strong mystical side that believed in symbols and porters. Proving that truth is stranger than fiction, she had been conceived in Swastika, Ontario, where her father owned a gold claim (typically, no gold was ever found there) and her middle name was indeed Valkyrie.

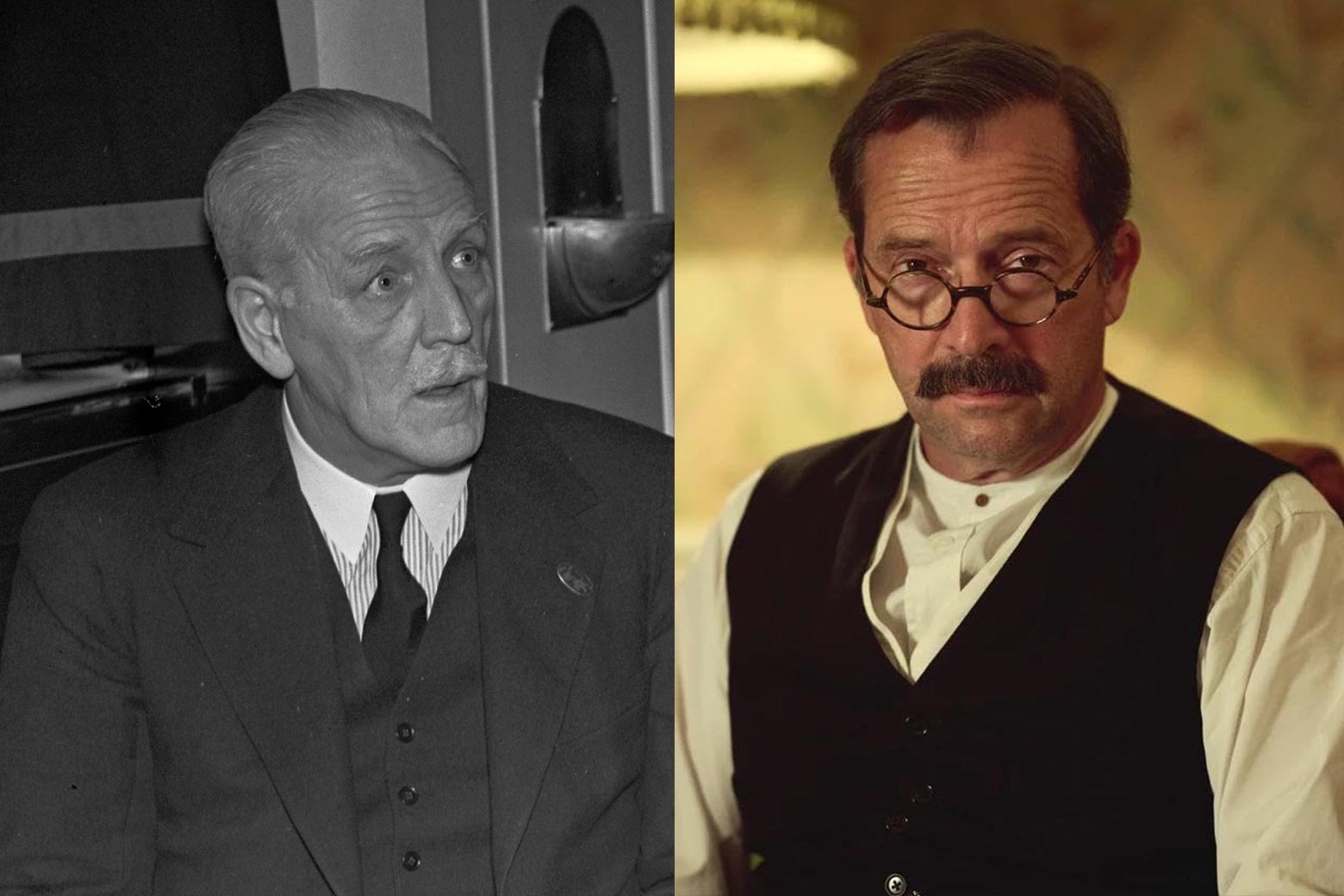

The origins of her name offer a clue as to why Unity and Diana's fascist sympathies went beyond even the fascism-curious position of many in the British upper classes. Unity was given the middle name of Valkyrie at the suggestion of her grandfather, the first Baron Redesdale. This Lord Redesdale was good friends with a British-born expert on German culture (and Wagner in particular) named Houston Stewart Chamberlain , who wrote an influential book called The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century , which was filled with extreme nationalism and virulent anti-Semitism, and argued that the greatness and creativity of Europe was due to the Western Aryan peoples and that any Jewish influence had been primarily negative. The book became a foundational text of the National Socialism movement and a huge influence on Hitler, and the foreword happened to have been written by the Mitford girls' grandfather, Lord Redesdale.

Even Muv, depicted in the series as a calming, practical influence on the mercurial Favre, had crackpot inclinations that might qualify her for a job with the Department of Health and Human Services under RFK Jr. For one thing, she was an anti-vaxxer. For another, even though she became more Nazi-leaning after visiting a Nuremberg rally with Diana and Unity in 1938, she had Old Testament food preferences and wouldn't use pork or shellfish in recipes.

She certainly did. Though the series does not shy away from dealing with the letter Unity wrote while in Munich to the Nazi house organ Der Stürmer expressing her support for their suppression of “the Jewish problem” and how horrified, not to mention mortified, her family is when it's picked up by the London papers, it does not fully convey just how bad the letter was. Not content with a final sentence that reads “We think with joy of the day when we shall be able to say with might and authority: England for the English! Out with the Jews!” she adds a postscript requesting her full name be used, not just her initials, because “I want everyone to know I'm a Jew hater.”

Faced with keeping characters who are enthusiastic Nazis at least somewhat sympathetic, one can see why Williams turned down the volume on the strength of Unity's convictions a bit. By contrast, in her book The Sisters , on which the series is based, author Mary Lovell writes, “We know she thought Streicher's act in making Jews crop grass with their teeth amusing, and that she approved when a group of Jews were taken to an island in the Danube and left there to starve.”

In the series, Diana starts a torrid affair with the charismatic Oswald Mosley even though she is married to the kind, handsome, and fabulously wealthy heir to the Guinness fortune, Bryan Guinness. Even after her divorce from Guinness and the death of Mosley's wife from peritonitis, Mosley wants to put off marrying Diana because, he says, the scandal of marrying so soon after becoming a widower will ruin his political career. (This, it should be noted, doesn't stop this moral void of a man from having his own affair with his late wife's sister, however.)

But by the summer of 1936, Diana has finally persuaded Mosley to marry her, partially by coming up with the solution of getting married in Germany, where Hitler can ban the papers from reporting on it, thus limiting any bad publicity. Not only do they get married in Germany but, thanks to Unity's efforts, the Führer himself awaits the marriage.

This is all true, but again, it's not the full story. Not only did Diana get married in Germany, but she got married in the home of Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's noxious minister of propaganda. Hitler may have attended despite not being overly impressed by Mosley, not because of Unity but because Diana had become close friends with Magda Goebbels, the minister's wife. So devoted was Magda to the Nazi cause that as the Allies marched on Berlin, she gave her six children cyanide capsules before their parents killed themselves rather than let them grow up under Allied occupation.