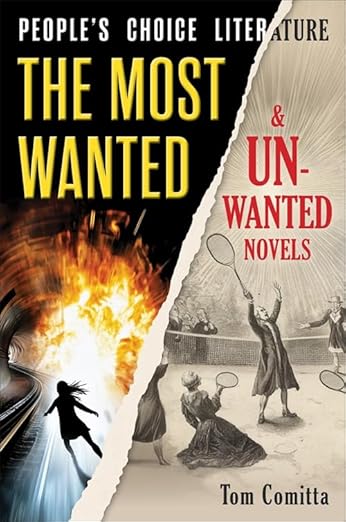

What Do Americans Actually Want to Read? One Author Crunched the Numbers—and Wrote It.

In the 1990s, the Russian-born conceptual artists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid hired professional polling firms to survey 1,001 people about what they liked most and least in a painting. The artworks they created using this information, the public's “most wanted” and “least wanted” images, were published in Painting by Numbers: Komar and Melamid's Scientific Guide to Art . (The “most wanted” painting was a landscape with water, wild animals, and George Washington; the “least wanted” was an angular abstract in fuchsia and yellow.) This enterprise proved so amusing that the pair, in collaboration with composer Dave Soldier, repeated the experiment with popular music, releasing the “most wanted” and “least wanted” songs together on a CD with a cover photo of all three men wearing white lab coats and pointing at a calculator. Sadly, the pair stopped short of what I view as the greatest challenge: producing novels that reflect what Americans like and dislike in fiction. Now, at last, with People's Choice Literature , by the writer/artist/composer Tom Comitta, a new “scientist” has taken up the task.

People 's Choice Literature offers its readers two novels for the price of one. The first is a thriller whose heroine tries to prevent her boss, a new age–y tech mogul, from launching a quantum computing network that will bring about a total surveillance state. That's the most wanted one. The least wanted novel is much harder to summarize, encompassing such ostensibly despised elements as stream of consciousness, explicit sex scenes, an extraterrestrial setting, metafictional commentary on novel-writing itself, talking animals, second-person narration, and tennis. Because this least wanted novel is such an extravagant farrago of weird elements, it may sound more entertaining than its counterpart. However, Comitta (who uses they/them pronouns) is sufficiently dedicated to their project that it is not. They have diligently included, for example, some long, dull epistolary passages about a polar expedition—a style and setting that 1,045 survey respondents found particularly unappealing. Full disclosure: While Most Unwanted often made me laugh, it also put me to sleep five times.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Most Wanted is a surprisingly competent genre novel, although the question of why this surprised me prompted some reflection. The belief that, say, the thrillers of James Patterson are so rudimentary and formulaic that anyone could write one is widespread but erroneous. True, Patterson's novels are extremely basic. Nevertheless, if anyone could write them, many more people would have success in doing so, and the bestseller lists would feature more authors not named James Patterson. It's harder than it looks.

The most refreshing aspect of People ’s Choice Literature is Comitta’s genuine curiosity about how such books are crafted. In writing Most Wanted , they didn't just take into account what readers said they wanted. They also read more than 20 thrillers; studied 2016's The Bestseller Code , a book that purports to use data analysis to “reveal a secret DNA of bestsellers”; and watched online courses taught by David Baldacci, Dan Brown, Walter Mosley, and, of course, James Patterson. While Comitta found thrillers to be “largely a masculinist, right-wing art form”—one presumably not to the tastes of an experimental writer who eschews masculine pronouns—they nevertheless paid a degree of attention to the genre that even many of its fans can't be bothered to devote to it, often to great comic effect.

In the book's introduction, in which Comitta explains the method and parameters of their project, they note that “nearly all American thrillers feature a love interest who is a current or former FBI agent,” and also that the hero is frequently named Jason, so the novel's heroine, Alix, teams up with the hunky Special Agent Jason Stone. Comitta also observed that thrillers always mention both the make and model of every vehicle featured in the narrative, a detail that becomes increasingly hilarious as the novel's characters are threatened by a series of homicidal Ford Fusions under the direction of the villain's quantum computer. Comitta mimicked Dan Brown's custom of dropping in potted travel-guide descriptions of historical or cultural sites where the action takes place, a practice Comitta themself finds “repetitive and a real slog” to read, though they can hardly argue with Brown's success. Danielle Steel's habit of repeating chunks of exposition “almost verbatim from one page to the next” struck Comitta as “not just emblematic of but virtuosic in the world of thriller writing,” leading them to declare Steel “Gertrude Stein with a Lifetime subscription.”

Comitta also used OpenAI's Playground, the most advanced large language model before the release of ChatGPT. The fact that Playground offered up “flat” prose that Comitta would then heavily edit struck them as being particularly appropriate for this experiment, given that, like LLMs, commercial fiction tends to draw from much-frequented wells. This, Comitta writes, “offered a polyvocality to the writing that seemed to resonate with the many perspectives represented in the poll results.” Few people read thrillers for the prose, of course, but along with the genre's Ford Fusions and Jasonmania, Comitta also picked up a good feeling for the plotting and pacing required of the form. It's impossible to care about the banal characters in Most Wanted , but that's true of plenty of thrillers, and this one is certainly easy to read.

The same cannot be said of Most Unwanted , a novel that ricochets all over the place, from a colony on Mars founded by tennis-playing refugees fleeing an Earth taken over by anthropomorphized cats, to a pastiche of Robinson Crusoe , to three pages in which the words and drift and float repeat over and over again, to a long digression in which Robin Hood and Maid Marian live in a throuple with a forest sprite. Most of the characters—including “you,” the main character, since the novel is told in the second person, a choice that is very unpopular unless you are Jay McInerney—are elderly aristocrats with names like Lord Brad and Lady Kimberly. Also, it is Christmas, and everyone talks about this incessantly.

Comitta interrupts Most Unwanted now and then (unpopularly, metafictionally) to explain why you're reading such nonsense: “West Virginia? Cat pirates? It's true, people don't want these things in their literature.” Although that is not strictly true. Faced with a dearth of productive prompts when it came to unfavored fiction, Comitta decided to pick up some ideas from the answers to an open-ended question in the People's Choice Literature poll. Respondents were asked, “If you had unlimited resources and could commission your favorite author to write a novel just for you, what would it be about?” The answers ranged from “Jay-Z writes my biography” to “It would likely be about Elves that are forced into hiding among humans.” (One of these responses was the source for the idea of the cat takeover, for example.) These requests are so eccentric they seem to put the lie to the bland mid-ness of Most Wanted , but really we are a nation of readers with tastes so diverse that the only things we can (mostly) agree on is that we like a fast-paced mystery with a love story, working-class protagonists, and—for a villain—a tech billionaire who's a bad father.

But if we like love stories so much, then how did romance end up as the least wanted fictional genre, according to the polled readers? How have classics remained classic—by definition books that people have loved for centuries—if “classic literature” clocks in at the third-least-popular genre, after romance and horror? And how do these responses jibe with the fact that novels by Emily Henry and Stephen King regularly top the bestseller lists? This aversion to “classics” offers a clue. For most readers, classics are the books assigned to us in school and read grudgingly and often uncomprehendingly. We most actively dislike books that have been times tested upon us, like a diner whose indifference to country music turns to hatred only when he can't eat at the local barbecue restaurant without being forced to listen to it at top volume. More often than not, our dislike of certain books is a reflection of how much someone else loves them and tries to push them on us: the teacher who makes you write a paper on Hemingway, the fellow book club member who just adores Colleen Hoover, the latest romantic trilogy that keeps cropping up in your TikTok feed.

It makes sense, then, that some parts of Most Unwanted were exactly what I wanted to read (I enjoyed an Inception -style chase scene through a series of virtual realities), while others, like the lengthy sex scenes, had me skipping pages. One of the respondents to that open-ended question on the poll about what sort of novel the reader would want custom-built just for them requested “an experiment poetry-prose hybrid work with an audiovisual component.” That sounds like one of the upper levels of hell to me—not quite a lake of fire, but getting there. But for someone else, it's heaven. What the people want, more than mystery or romance or science fiction, is the freedom to read the books that speak to their own idiosyncratic imaginations. Whatever books the people choose, what really matters is that they have a choice.