From classics to moralism. Three words as pompous as turkeys that kill literature.

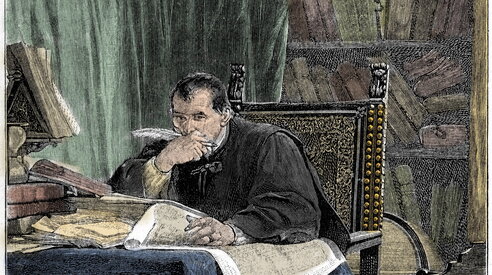

In the letter to Vettori, Machiavelli writes of entering “the ancient courts of ancient men, where […] I am not ashamed to speak with them” (Getty Images)

"Sharing," "relevance," "critical sense." Thus, humanistic teaching in schools transforms into activism. With all due respect to Machiavelli, who conversed alone with the "old men."

The expression turkey words comes from a 1924 letter by Pirandello to Telesio Interlandi , which I learned about while reading Sciascia's A futura memoria , which cites it. "Blessed is our country," Pirandello wrote, "where certain words strut along the streets, gurgling and fanning out their tails, like so many turkeys." Having been involved in schools for many years, and specifically in the teaching of literature in schools, I seem to notice that the way it is spoken and written is full of these turkey words, which are often just mental shortcuts, and are met with acquiescence even by those who, if given the time to think about it, would probably end up taking exception to those turkey words. Pirandello immediately observed that "it has always been seen that a little good has only come when [...] one has simply but resolutely approached these words, which immediately fled away, scattering here and there, their tails low and livid with fear." I'm not so optimistic. These are words I'm thinking of that, especially when wielded by fanatics, are unaffected by fear or shame, nor do they seem on the verge of retreat. But let's try.

* * *

You may have heard of a letter Niccolò Machiavelli wrote to his friend Francesco Vettori, telling him about his life as an exile in his homeland. Machiavelli spent his days partly reading "light" things that today we would consider very heavy ("Dante or Petrarch, or one of those minor poets, like Tibullus, Ovid"), and partly in the company of friends, engaging in games of chance. Then, in the evening, "I put on royal and courtly robes; and, appropriately dressed, I enter the ancient courts of ancient men, where [...] I feed on that food which is only mine and which I was born for; where I am not ashamed to speak with them and ask them the reasons for their actions; and they, out of their humanity, answer me."

Of course, I'm kidding. This is not only the most famous of Machiavelli's letters, but it's also one of the few pages of prose that, one might venture, almost all Italian schoolchildren have been and will be forced to reflect on for a few minutes of their lives. I don't know, however, whether the "textual analyses" administered in textbooks and in classroom explanations give sufficient consideration to the fact that here Machiavelli essentially says that the pleasures of the intellect are pleasures enjoyed in solitude . While others—the friends at the tavern, the petitioners—stay outside, the reader remains in solitary dialogue with the book before him.

So, if we try to draw a moral from this fable, we read it not to come into contact with human beings who are already close to us, nor even to strengthen our relationship with them, but to cultivate ourselves through the wisdom, intelligence and taste of the best among the human beings of the past .

Although many of us may perhaps share, perhaps with some distinctions, a point of view of this kind, it seems evident that contemporary humanistic education most of the time takes a completely different path , both in terms of substance and in the ways of its transmission.

In substance, it's clear that the "courts of ancient men" have lost much of their appeal , and that the cultural objects we nourish ourselves with—not just books, but also and above all films, songs, television series, video games—belong primarily to the present. This is especially true if we're talking about those who work in education; or more generally, if we're talking about people who aren't professional intellectuals . As for the methods of transmission, and this is the point closest to my heart, I seem to have noticed that the Machiavellian model—which encourages the solitary consumption of books—has been supplanted by an exactly opposite model, which encourages, above all else, sharing (this is the first of our turkey words).

In the public sphere, this is so obvious that we can skip the usual list: salons, festivals, public readings, book presentations attended out of politeness, or in the same spirit as those who stroll and window shop . And in recent years, the ongoing conversation on social networks has naturally been added, with Instagram and TikTok pages promoting reading, pop stars like Dua Lipa even having a column where they review books, invite authors, and engage in even interesting conversations. In such an extroverted world, it's not surprising that even serious cultural consumption ends up being defined as a social, dialogic activity, rather than an activity to be practiced in solitude; and that books are "talked about" rather than read .

Perhaps this push toward extroversion is less evident in the school setting ; but when I study textbooks, I observe that those who "practice" the texts, who are often teachers, and excellent ones at that, tend to place much more importance than in the past on discussion with classmates, once they've finished reading this or that anthology. "Do you think that, in writing to Vettori, Machiavelli aimed to use him to become friends with the Medici family again? Discuss it with your classmates and write a thousand-word account of the various positions that emerged in the discussion." Often, in keeping with modern teaching methods, the discussion is organized in the form of a debate , which—I quote from the IA's definition—"involves a structured confrontation between two teams on a specific topic, in which each team argues for or against a position. The goal is to develop students' argumentative, critical thinking, and communication skills." Sometimes, the mediation of the text is completely discarded, and the exercise takes the form of a "real-world task": "Organize an exhibition based on the text you've read. Write a short presentation and identify a suitable space in your city (a school, a museum, a conference hall, a sports hall)." Usually, the exhibition is multimedia.

Argumentation and communication skills, critical thinking, knowing how to book a sports hall—these are all blessed things, except that using literary texts for these casuistry exercises seems a waste, or even a category error: is there really nothing more urgent to learn from literature? Knowing how to argue is important, but it's even more important, and more difficult, to master the solitary art of individual reading. To this end, rather than endless "batteries" of exercises designed as group activities, more expedient text analyses are needed that, without excessive formalism, help students understand what is authentic and useful to them, taken one by one, on the page they've just read—reading that should, in fact, resemble Machiavelli's as closely as possible: silent and solitary. We read to grow, to sharpen our intelligence, and this requires at least a hint of the antisocial attitude of Machiavelli's evening. I have the impression that this truth isn't repeated enough.

* * *

These observations may sound a little harsh. Isn't reading both self-cultivation and communication with others? Of course it is. But I fear that the turkey-like word "sharing"—understood, I repeat, as a valorization of "we" over "I," of dialogue among peers over solitary dialogue with "old men"—I fear that this scholastic attitude has ended up influencing the choice of books, or portions of books, we ask our students to read.

To explain, I'll use a second turkey word, this time an English word, relevant, which obviously means "important," but in current usage takes on the nuance of "significant because it touches on issues close to our hearts." "A book's relevance today," says the AI, "depends on its themes and how they resonate with current issues." It's relevant because it resonates, that is, it establishes a sort of immediate emotional connection with the reader.

This obsession with relevance is linked to a school practice that almost always seems to me to be detrimental: the practice of uniting rather than separating, of valorizing similarities rather than differences . "Only connect" is a motto that may work at the highest levels of culture, for those who have already accumulated a profound experience of art; at the lower levels, it is an exercise in rhetoric and wishful thinking. In recent months, together with some collaborators, I have written the new national guidelines for the teaching of literature in schools, and I have also had to invent "interdisciplinary connections" (according to the ministerial format) for primary school. That is, I have had to try to build bridges between disciplines by speculating on the "synergies" between Italian and history, Italian and geography, Italian and physics. But I believe Antonio Calvani is right when he says that this interdisciplinary zeal is the fruit of a naive pedagogy (interview with "Orizzonte Scuola," May 2, 2025): "Among those who seriously practice interdisciplinarity, is there anyone who has reached that level without having undergone solid internal training in the discipline(s)? Ong has demonstrated the significance of the advancement of scientific thought with the advent of textbooks (texts capable of coherently and comprehensively enclosing closed knowledge) compared to more interdisciplinary, but scientifically much more frail, forms such as those of medieval knowledge or other more primitive models."

As we know, the disease has spread to the state exam, or perhaps, conversely, it has descended from the state exam to school practice. The fact is that, at the end of the fifth year, eighteen-year-olds, almost always uneducated, are asked to craft a speech that combines (I'm copying from one of the many sites that offer students paid exam preparation materials) "written texts, images, works of art, excerpts from documents, drawings, logos, or other materials." These are tests that would embarrass Max Weber. Those who have had the fortune of witnessing them have come away with a sense of dismay: at the students' ignorance disguised as knowledge, at the examiners' embarrassment, at the woeful idiocy of the entire machinery.

On the other hand, if disinterested art is viewed with suspicion, it suffices to demonstrate that it too, upon closer inspection, is ordered to a purpose that concerns us, and therefore also relevant. However, it's not at all certain that this kind of connection between the past and the present is produced by qualitatively superior texts; on the contrary, those that resonate may be texts that easily appeal to the naive reader, partly because they are naive themselves, or, conversely, very clever in their desire to create the aforementioned, superficial, emotional connection. And it's also likely that as we go back in time and delve deeper into the pages of "antiqui huomini," their relevance diminishes proportionally, because—rhetoric aside—it's very difficult to imagine that the authors Machiavelli entertained with (the lyrical Dante, Petrarch, Tibullus) could say much to a schoolboy new to literature. With the criteria of artistic excellence and historical significance—the two fundamental reasons for reading literature—fading or being relegated to the background, on the one hand, we run the risk of privileging those texts that seem most in tune with current issues, and that, in short, touch on questions that the political agenda or widespread sentiment leads us to consider more lively and interesting than the questions that—to return to him—Machiavelli debated with Livy. On the other hand, we arrogate to ourselves the right to update (that is, to make relevant) works of the past, obliterating their original meaning and declaring them outright our contemporaries. This is what happens, for example, in these lines introducing a series of lectures entitled Classics Against at the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza: "It's a question of cities, of civilization, of polis, and of democracy. To know what to do in this time of migrants, of children, women, and men fleeing war, hunger, and suffering, the answers are not easy to find, certainly they are challenging [...]. For three thousand years, we, citizens of Europe, have had some answers. Just reread Homer's Odyssey. Just look at Aeschylus's The Suppliants. It's all there, every problem."

Here, in a few lines, is a conflagration often observed in current discourse on literature: between the problems and good causes of the present (war, migrants, hunger) and the literature of the past. "There's everything, every problem." It's this kind of chaotic generalization I alluded to earlier, speaking of an approach to books that encourages us to value analogies and ignore differences. And it seems to me that the entire long history of civic education in Italian schools can also be interpreted in this moralistic vein.

* * *

Over the years, I've published several high school literature textbooks that need to be updated periodically, especially in the Themes section. This isn't a novelty; almost all textbooks have a theme section, allowing teachers and students to read texts from different eras and to observe—reflected in literature—the persistence of certain simply human constants: love, growing up, death, madness... A few days ago, the excellent editorial staff I work with sent me this message: "We need two themes per year (six in total). The topic must be educationally interesting + relevant + suitable for civic education + offer a minimum of scope for interdisciplinary discussion."

In line with this program, the topics we will choose will not be purely literary (say: the forms of short fiction, or allegory from Dante to Baudelaire) but themes that lend themselves to connections (another illustrious turkey-word, dated but evergreen) with that supra-discipline that is civic education. That is, we should seek out above all non-literary texts that can be included in that field: newspaper articles, manifestos, international treaties, legal provisions.

Throughout history, there have always been those who wanted to make literature the handmaiden of this or that master. For Tolstoy in What Is Art?, it was to be an instrument of moral progress aimed at universal brotherhood. For the young Calvino, the task of writers was "to transform into poetry the new morality of communist man that is clearly emerging in millions of men throughout the world." And there have been times, and there still are times, in which literature has placed itself at the service of nationalism, of founding myths. But there are also less violent forms of subjugation. In an essay from the early 1980s, Fortini spoke of the subordination of literature to the all-powerful social sciences ("It is no longer clear what place the literary text has among the many 'sciences of man'"). And now we have arrived at literature subordinated to civic education. But with two significant differences compared to the past.

First, while past trends inevitably prompted countertrends, with the communist viewpoint producing the anti-communist viewpoint, and the nationalist viewpoint being opposed by ecumenism, civic education seems to have no opponents: for what aesthete, snob, or elitist could fail to exploit the educational potential of literature? In fact, the reintroduction of civic education as a curricular subject in Italian schools was voted unanimously by all Italian parliamentarians: a few dozen abstentions, no votes against. I can't say how many other times this has happened in recent parliamentary history, how often a law with such a significant impact on all citizens—all those who go to school, or send their children there—has found consensus among the right (which formulated the proposal), the left, and the center. I mean, the presence of civic education as an ideal framework is more evanescent than that of ideologies or faiths, but it's perhaps destined to last longer, because it's hard to see anyone—in the name of what, really? Of the distinction between aesthetic and moral judgment? Of purposelessness?—who could object to civic duty and good manners. Once, in the controversy over the harmful effects of rock on adolescent minds, Frank Zappa was asked if there were any lyrics to songs released in recent years that he would prefer his children not listen to. Zappa replied: "We Are the World." An excellent answer, which means: artistic education is something entirely different from edification. But you have to be Zappa to afford it.

Second, while past trends expressed a clear—and therefore debatable—map of values and disvalues (even summarized in phrases like Franz Kafka or Thomas Mann?), civic education in schools seems to have more elusive goals. It encourages virtue in every field and, during Italian lessons, invites virtuous reading and reflection, especially (returning to our definition of relevant) on the "current issues" that are shaking up the world today. Functional to this end is the maturation of the student's critical sense, or critical spirit: which is the third and final key word in my discussion.

* * *

After reading the aforementioned national guidelines on literary education, a colleague pointed out that I should have added precisely this: the acquisition of critical thinking. And even in the dossier the ministry sent me—which contains the opinions of various scientific associations—this request surfaced repeatedly. "The study of literature starting in elementary school," write representatives of one of these associations, for example, "is instrumental to intellectual maturation and the secure possession of critical thinking." I've tried to understand precisely what critical thinking means, but I can't say I've truly succeeded. A simple definition might be this: the ability to see inside and behind things in the world, beyond appearances, to understand their true nature. But, on the one hand, isn't this a goal that's too ambitious? Isn't it, after all, another name for that intelligence that we spend a lifetime accumulating and honing? On the other hand, I believe it's a common perception that precisely those who think they possess a critical sense turn out, when tested, to be the most conformist—that is, the least critical—of human beings. In particular, it seems to me that in certain schoolbooks, and in the minds of their authors, critical sense ends up corresponding to a generic anti-capitalist sentiment, articulated, however, not in the manner of—let's say—Piketty, which requires skills that are too difficult to develop, but in the manner—let's always say for the sake of brevity—of Don Milani: we must love the poor (or abused women, minorities, people with problematic sexual identities, the disabled). Applied to the past, as it inevitably should be in a literary history textbook, it means forcing texts, obliterating what they say.

So here they are, one last time in a row, our turkey words: sharing, relevance, critical thinking. In themselves, they are not sins. They become sins if, as I believe is happening, they convey the idea that literature serves to understand the world first and foremost rather than to understand oneself. I believe the opposite is true, and that it is important to reiterate this, especially during the formative years, when one is weak, disoriented, and unaware of oneself, but also, at the same time, very ready to embrace causes that are mostly ignored. Reading certain humanities textbooks, listening to certain colleagues, and seeing how many good causes are being targeted in the cultural education of students, I often get the impression that many interpret humanities education as a form of activism. It seems to me that the turkey words I mentioned here support this misunderstanding, and so they should be used with great discretion, or not at all.

All this said, it's logical to observe that words come after things, and that turkey-like words, unimportant in themselves, reflect a concept of education that would be worth reflecting on more fully. Without further ado, and in light of what I've observed, I think I can conclude this way: as faith in the classics, the canon, the humanistic tradition, and all the other vast and already fragile cultural ideals believed in until a few generations ago, mostly in the spirit of devout atheists, wanes, literary education increasingly takes on the characteristics of moral edification, especially when it is administered by naive and unprepared teachers who have never had that faith, and who are instead filled with missionary zeal. This type of education views literature not as an end but as a means: consistently, it recommends texts that convey virtuous ideas, while paying little attention to their quality and historical significance, and has no patience for texts that, due to their complexity or ambiguity, are unsuitable for persuasion. The effects of this distortion are already visible in some school anthologies, and in the medium to long term, I believe they will have an impact on the way future generations will view literature.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto