Mysteries and pleasures of the night

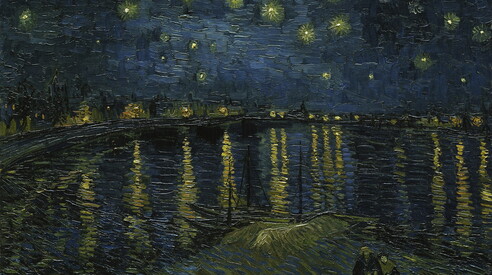

Pascoli's perspective in "Notte dolorosa" and that of Van Gogh's "Starry Night Over the Rhone": from the limits of everyday life to the vastness of the universe

In poetry, painting, and art, the night seems an opportunity for privileged self-observation, the place of that solitude which, retreating into interiority, opens up the most intense companionship. The hour when desire takes flight. Chopin, Saba, the centenary of the publication of "Evening on a Festive Day"

“Sweet and clear is the night and without wind, / And quiet above the roofs and amid the gardens / The moon rests,” writes Giacomo Leopardi in one of the most beautiful incipits known to our literature, outlining an image that reverberates throughout his poetry and finds reflections in countless other authors. The night – a harbinger of serenity but also of restlessness, of rest but also of subterranean trepidations – has always been a sort of half-open gateway to the mystery of the human being and his existence , to the desire that animates him, to the silence that contrasts with the activities of his actions, to his deepest questions. “What are you doing, moon, in the sky?” wrote the poet from Recanati, posing a question that continues to resonate in man of all times: “For what purpose so many torches? / What is the infinite air doing, and that profound / Infinite serenity? What does this / immense solitude mean?”

It is perhaps no coincidence that a nocturnal image opens the first pages of the entire Zibaldone (“It was the moon in the courtyard”…) and then accompanies the author to the threshold of his most unforgettable verses, such as those in which he invokes the “Placid night, and modest ray / Of the falling moon,” those in which he turns to the “Vague stars of the Bear…” or those in which he confides, in a dark atmosphere, his painful memories (“O gracious moon, I remember…”). The nighttime hours – when “everything in the world is at rest” – are a constant presence in Leopardi's poetics, as demonstrated by the annotations the author occasionally inserts unannounced into his writings, drawing us into the here and now of his creative endeavor: “The nighttime creaking of weather vanes drawing the wind”; and elsewhere: “Seeing the moon travel with me.” These are moments captured forever in quick snapshots, simple notes that foster empathy and almost make us feel like we're right there with him, at his desk or in the moments just before sleep: "I hear the tower clock chiming from my bed. Memories of those summer nights when, as a child, left in bed in a dark room with only the shutters closed, between fear and courage, I would hear a certain clock strike."

For Leopardi, the descriptions of the night are "extremely poetic" because "by confusing the objects, the mind conceives only a vague image of them."

Of dizzying depth is the image of the evening when, in his room, he hears the song of a passerby coming from the street, "fading away little by little," immortalizing it as a significant presence in the verses—published exactly one hundred years ago—that close La sera del dì di festa . In fact, during the same period, he notes: "My pain in hearing, late at night following the day of some festival, the nocturnal song of passing peasants." In a time not too distant from our own, in which men experienced a closer relationship with the surrounding nature, the arrival of darkness was captured with precision by poets, recording the unstoppable advance of the shadows ("The day's ray in the west having died down, (...) Behold, the night is troubled, and the semblance of the sky grows dark," he writes again) and capturing the elusive transition between light and darkness. The breath of the wind, a distant echo, the sound of footsteps become, in the delicate and majestic setting of nighttime, something more than their usual meaning. Leopardi himself explains it to us: "The (...) descriptions of the night (...) are extremely poetic, because the night, confusing objects, the mind conceives of them only a vague, indistinct, incomplete image " (September 28, 1821). The advancing darkness is a moment of unparalleled evocativeness, in which the subject finds himself more intensely in the presence of the immensity that surrounds him and the perception of things seems to become denser and more vibrant. In poetry, painting, and art, the night seems an opportunity for privileged self-observation, the place of that solitude which, folded in on interiority, discloses the most intense companionship.

Accompanied by silence, the nighttime gives greater prominence to thoughts, favoring an otherwise unknown immersion in oneself, while the ethereal nature that things assume in the dim light envelops them in mystery: it is something similar to what happens in the musical form of the Nocturne, conceived by John Field in the late eighteenth century but brought to absolute development by Frédéric Chopin: the crepuscular nature of his scores becomes an opportunity for an introspection that only the darkness of shadows – removing from sight what is distant – can foster, allowing the composer to investigate, as if by the dim glow of a hearth, the most hidden corners of his own feelings.

The twilight nature of Chopin's scores becomes an opportunity for an introspection that only darkness can foster.

Even in the most ancient texts, the wonder that darkness inspires finds admirable expression, as in a famous passage from the Iliad, Hector and Ajax interrupt their duel precisely because of the arrival of darkness: "Let our weapons rest, and let the contest cease. We will fight again until the Fates divide us and grant complete victory to one or the other. Now night is falling, and the reason for the night is not broken." The descent of darkness highlights the mysterious "becoming" of reality, and the night—violated by contemporary man with his artificial lights, but perceived as sacred and therefore religiously respected by ancient civilizations—obliges everyone to pause before the sovereignty of nature. Sunset (like, since prehistoric times, the rising of the sun) becomes a sign of the mystery that governs the fate of the world and to which man knows he must bow. Perhaps this explains the repeated attention in Homeric poems to the formula that closes more than one scene: "The sun set, and the streets were veiled in shadow." Similarly, in the powerful and somewhat self-contained opening of the Odyssey, Telemachus, after the unexpected events that have brought him to the threshold of adulthood, goes to his room to sleep but fills the silence with his whirling thoughts: his dialogue with Athena, her invitation to assume responsibility, his desire to set sail (in the sea but, metaphorically speaking, in life) in search of his father: "And there, all night, wrapped in soft wool, Telemachus thought in his heart of the journey the goddess had suggested." Once again, the night—both tenuous and dramatic—becomes the locus of an internal dialogue, of a coming to terms with himself.

Amidst cheers and turmoil, stillness and anguish, art and literature reveal the night to us in its most diverse guises, in its polymorphic, ever-changing, yet always irresistibly fascinating identity: "I turn / toward the sacred, ineffable / mysterious night," writes Novalis. It's easy, then, for the mind to return to the sequence, at once painful and sweet, of Manzoni's Unnamed Man, who, after his encounter with Lucia, retreats—almost a victim of an unknown good—to his room "with that vivid image in his mind, and with those words resonating in his ear," so powerful now that "everything seemed changed." The darkness in which he is immersed, “turning angrily in bed,” welcomes the oxymoronic presence of that “rage of repentance” (“I ask forgiveness? From a woman?”) that deprives him of any possibility of rest, or at least distraction, forcing him to fix his mind’s eye (curiously the same expression that appeared in Homer) on the figure, full of fragility and strength at the same time, of the girl who is bringing about his radical conversion.

Literature and soldiers in the trenches: Mario Rigoni Stern observes the firmament becoming an unexpected link with distant affections

How can we not recall, in a moment closer to us, the night that becomes the setting for dramatic episodes of war, such as the "entire night / thrown next / to a comrade / massacred" vividly described by Ungaretti, which nevertheless transforms into an occasion for a sudden, Caravaggesque contrast with the attachment to life ("I wrote / letters full of love") and with the possibility of recognizing more distinctly one's own identity as a human being ("In this darkness / with my frozen hands / I distinguish / my face"). Moving, in that context, is the contrast between the silent night, punctuated by brief rest periods for the soldiers in the trenches, and the possibility, in those same moments, of renewed hope, as in the passage where Mario Rigoni Stern observes the firmament unexpectedly forming a link with distant loved ones: "The stars that shine above this hut are the same ones that shine above our homes." They are fleeting moments but capable of leaving a mark, placing humanity and its limited, sometimes irrational experiences before the infinite horizon of being: “The sky was starry and sparkling,” writes Dostoevsky in White Nights , “so much so that, after contemplating it, one involuntarily wondered whether irascible and angry men could live under such a sky.”

The night is a moment that seems, to use the words of Clemente Rebora, to "watch over the instant" where the event of poetry resides.

Far from being a void, silence becomes the context in which things appear in their fullest relief. It is in the nighttime hours that Fernando Pessoa perceives "a difference in the soul / and a vague sob," perhaps the emergence of what Umberto Saba would call "acute / lacerating nostalgia," in a sort of unusual epiphany of reality: "In the blue sky all the stars / seem to remain as if waiting," writes Giovanni Pascoli in a suggestive verse. In the poem entitled Imitation, Saba also offers a description of the hour of sunset ("The blue fades into an all-star blue. (...) The moon has not yet been born, it will be born / late") and in that very moment he perceives the emergence of an unexpected clarity: "And in me a truth / is born, sweet to repeat." It is in the evening that things—even those seemingly unimportant—take on intensity, offering those willing to pause to experience the density of the moment, the depth of each instant, the unknown depth of surrounding reality. Nothing is ordinary for someone who has experienced the depth of vision, as Saba further clarifies: "I sit at the window and look. / I look and listen; but in this lies all / my strength: looking and listening." The night is a moment that seems, to use the words of Clemente Rebora, to keep watch over the moment: the possibility of grasping—in the shattering of the frenzy that accompanies the daytime hours—the value of seemingly ordinary moments, such as that captured in the verses of Angelo Poliziano: "The night that hides things from us / returned shadowed by a starry cloak, / and the nightingale under its beloved branches / singing repeated its ancient lament." It is precisely here that poetry comes into play, as a gaze that penetrates appearance, offering attention the opportunity to delve – to use Montale's words – into “silences in which things / abandon themselves and seem close / to betraying their ultimate secret” or the possibility of being surprised – as an incisive verse by Mario Luzi states, “present in this moment of the world”.

Here then is the unprecedented intensity with which Pascoli, returning home in the evening, listens in the gathering darkness to the birdsong (“I heard those / voices in the shadows, in the silence, clear; / and it seemed to me like the humming of stars”) or the cry of the nocturnal scops owl overlapping with the march of wagons on the road (“A chirping sound from I know not what tower. / It is midnight. A double sound of a stamping / is heard, passing. There is in the distant streets / a rolling of wagons that stops”). And finally, the quiet of the “taciturn constellations” puts an end to the day’s agitations: “The day was full of lightning; / but now the stars will come, / the silent stars.” But even more surprising, in Pascoli's "night as black as nothingness", is the occurrence, so to speak, of a vertical, dizzying and sudden leap: in the silent heart of the darkness (while "the waters, the mountains, the moors sleep") the great silence is suddenly pierced by a maternal voice ("a song / (...) of a mother, and the motion of a cradle"), and it is there that the gaze - with the same perspective observed in Van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhone , painted only three years earlier - immediately shifts from the edge of the everyday to the vastness of the universe, with a gesture that creates an unexpected, profound bond between these two dimensions: the child "cries; and the stars pass slowly".

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto