Odoardo Beccari, Sandokan's other father

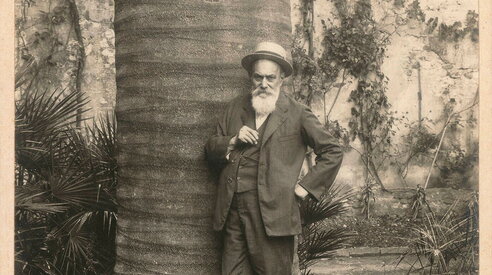

Unidentified author, 1915-1920, Odoardo Beccari photographed in the garden of the Bisarno Castle (Villa Beccari) in Florence (Alinari Archive - Beccari Archive)

Emilio Salgari studied the accounts of the adventurous naturalist in the good graces of the real Rajah James Brooke

“In Borneo, the largest of the islands of Malaysia, there exists a country in which a Rajah and a Rani, of the purest English blood, govern absolutely a state almost two-thirds the size of Italy, which has its own fleet and army, but which is not yet connected by a telegraph line with the rest of the world, which has no railways or even roads, and which is instead for the most part covered by interminable and dense forests, in which the Orang-utans roam. Here the inhabitants lead a primitive life, and in part are still savages devoted to hunting their own kind, whose smoked heads they keep suspended inside their dwellings. […] This is the Kingdom of Sarawak , which owes its origin to a superior, adventurous and enterprising man, Captain James Brooke .”

Sarawak, James Brooke: does this remind you of something? Perhaps something you read as a child? Or a hit TV series from the 1970s?

“The flag of Rajah Brooke, the Exterminator of Pirates!” he exclaimed, with an untranslatable tone of hatred. “Tiger cubs! Boarding! Boarding!… A wild, ferocious cry rose between the two crews, who were not unaware of the fame of the Englishman James Brooke, now Rajah of Sarawak, a merciless enemy of the pirates , a great number of whom had fallen under his blows.”

This last passage comes from one of the best-known novels by the writer Emilio Salgari , Le tigri di Mompracem (1900, but the volume edition is preceded by a serial edition entitled La tigre della Malesia from 1883-1884). The first is instead taken from the essay by the Italian naturalist Odoardo Beccari , Nelle foresta del Borneo (1902, but there were already numerous previous accounts of his travels in Malaysia, begun in 1865).

So James Brooke, rajah of Sarawak, was not a character born from the imagination of Emilio Salgari and then masterfully played by the actor Adolfo Celi, but a real figure .

Before we get to Brooke, however, we need to get to know Odoardo Beccari better. Portraits show him with a determined, almost grim expression, "of a man of exceptional physical and moral strength" (as Stefano Mazzotti puts it in his beautiful Esploratori perduti , Codice, 2011). His life was not an easy one. Born in Florence in 1843, he lost his mother almost immediately to suicide, and his father shortly thereafter. Entrusted to his maternal uncle, he ended up in a prestigious and strict boarding school, where he developed an early interest in botany. In 1861, he entered the University of Pisa to study natural sciences, but completed his studies in Bologna two years later. It was here that he met the Genoese marquis Giacomo Doria, also a naturalist and founder of the Natural History Museum of Genoa. They shared a desire for a scientific expedition to exotic lands, and they quickly chose an ambitious destination: Sarawak, in the northwestern part of the island of Borneo, now part of Malaysia. Ambitious, but not unprepared, the two men. To carefully prepare for the trip, Beccari visited the main European research centers and museums housing specimens from those regions. In London, in particular, he met Charles Darwin and then, of course, the adventurer and politician James Brooke . An almost legendary figure, Brooke was born in India in 1803. He earned the trust and gratitude of the Sultan of Brunei during several local uprisings; this gratitude earned him the position of Rajah of Sarawak starting in 1842.

Beccari's partnership in the 1860s with Marquis Giacomo Doria. They chose Borneo as the destination of their scientific expedition.

In the following years, he carried out numerous reforms, expanded his territories, and relentlessly fought the threat of piracy and slavery. The Queen bestowed numerous honors on him. But when Beccari met him in London, the now sixty-year-old Brooke's power was waning and he was increasingly controversial, even in his homeland, for his anti-piracy methods and accusations of embezzlement. But he knew Sarawak like no other European and had already supported several explorations, such as that of the great British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. Brooke entrusted Beccari and Doria to his nephew Charles, whom he had already identified as his heir. The two set sail for Borneo in the spring of 1865; Beccari was just twenty-two years old. After a very long journey and numerous stops, on June 19, 1865, they arrived in Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, where they established their base, building a hut on stilts. Beccari was immediately enchanted by the land . “The forest of Borneo is so multifaceted at different times of day, as it is with the seasons and the weather, that no description can ever adequately convey its essence to anyone who has not lived there. Its aspects are infinite and varied, like the treasures it conceals. Its beauties are inexhaustible, as are the forms of its creations. In the forest, man feels truly free. The more one wanders through it, the more one falls in love with it; the more one studies it, the more one remains to know. Its shadows, sacred to science, satisfy the spirit of the believer as well as that of the philosopher.”

He must defend himself from snakes and leeches. He meets "the great ape of the forest: the orangutan, 'man of the woods'."

When Doria was forced to return home due to health problems, Beccari continued his tireless research alone, remaining in Borneo for three years. He often subsisted on boiled rice and had to fend off snakes, ants, and terrifying leeches. He collected and catalogued countless botanical and zoological materials. He was struck by plants never before seen, such as the mysterious Rafflesia, with flowers "56 cm in diameter." Far more controversial today is Beccari's interest in " the great ape of the forest: the orangutan , literally 'man of the woods' to the Malaysians." This is how the naturalist described his encounter with a peaceful orangutan. “I could distinguish only a little red fur among the foliage; yet there could be no doubt, it was a mayas sitting on its nest. I could see clearly that the animal immediately realized it had been discovered, but it did not show any fear of our presence, nor did it try to flee; rather, it peeked out from between the branches and then descended a little, as if wanting to observe us more closely, clinging to the stems of a liana hanging from the branch on which it had previously perched. […] It was in this position when I fired. After remaining suspended for a few seconds from a branch, it fell to the ground.” Thanks to Charles Brooke, he reached the island of Labuan on a gunboat, a place of strategic importance where James Brooke had become governor by appointment of the British Crown. Here, Beccari was fascinated by the vegetation, rich in orchids. Inland, he was hosted in the villages of the Punàn and Buketàn tribes, fearsome headhunters. The island is well known to readers of Salgari.

“What news from Labuan? Those poisoners of people, those land-robbers, those English dogs, are they still camped there on the island? […] But tell them to lift a finger against Mompracem!... The Tiger of Malaysia, if they dared, would know how to drink all the blood from their veins! – Did you know that I have heard again about the Pearl of Labuan? "Ah!" said the pirate, jumping to his feet. "This is the second time that name has reached my ears, and it has strangely struck a chord in my heart. Do you know, Yanez, that this name strikes me strangely?" "Do you even know what this Pearl of Labuan is?" – No. I'm still not sure if it's an animal or a woman. In any case, it makes me curious. – In that case, I'll tell you it's a woman. – A woman?… I would never have suspected it. "Yes, my little brother, a young girl with scented brown hair, milky skin, and enchanting eyes. Akamba, I still don't know how, was able to see her once, and he told me that to forget her, he needed rivers of blood, and at least fifty boardings."

(Emilio Salgari, The Tigers of Mompracem, 1900).

By now severely weakened by hardship and malaria, Beccari embarked in Singapore in January 1868 and finally landed in Messina in March of that year, after a three-year stay in Borneo. Once in Florence, he transcribed and published his notes in journals such as Cosmos and La Nuova Antologia ; notes that also captured the attention and imagination of Salgari . But he was also harboring another ambitious project: a nature trip to New Guinea . In November 1871, he set out with the naturalist Luigi Maria D'Albertis and arrived there the following March. Here, the richness of animal and plant species was offset by difficult living conditions, with D'Albertis falling seriously ill and forced to return to Italy. Suffering from various illnesses, including smallpox, Beccari resisted and visited numerous islands in the Indonesian archipelago, including Bali and Java. From here he embarked in 1876 to return to Italy, once again laden with materials ready to enrich the knowledge of naturalists. "Without fear of being accused of the slightest exaggeration," wrote zoologist Enrico Giglioli, "I can declare that no scientific expedition in any time or place had achieved such rich and interesting results in the short space of time it took." Now well-known and esteemed, Beccari, however, could not stand still, and in 1877 he set off again with Enrico D'Albertis, Luigi Maria's cousin, to India, Singapore, Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand .

He was the first to describe a specimen of Amorphophallus titanum, “a gigantic and monstrous flower” with a nauseating smell of rotting flesh.

His stay on the Indonesian island of Sumatra , rich in rare bird species, rhinoceroses, and tigers, was particularly enriching and fascinating. Here he also made an important botanical discovery, describing a specimen of Amorphophallus titanum , "one of the greatest wonders of the plant world." Beccari even placed a reward on the latter, and shortly thereafter two natives carried him on their shoulders "the largest unbranched inflorescence in the world [...] a gigantic and monstrous flower" (the flower is three meters tall and two meters in diameter, the leaf two meters) with a nauseating odor of rotting flesh—hence the English nickname "corpse flower ." The impression on European naturalists was such that many long doubted the flower's real existence, but its success with the general public was also enormous, especially when a specimen was successfully brought to flower in a greenhouse in London thanks to Beccari's seeds.

This story, which Tim Burton would have loved, did not escape Salgari's attention . In his 1896 novel The Shipwrecked Men of Oregon, the two protagonists find themselves crossing Borneo on foot and come across gigantic flowers.

“Rafflesias […] are the largest known, having a circumference of three meters and a weight of seven or eight kilograms. These plants, first discovered by the Italian Odoardo Beccari in 1778 [sic], on the slopes of the Singaleg volcano, in the province of Padang, in Sumatra, produce a single, gigantic leaf, over ten meters high and two or three meters wide; from the center of this leaf subsequently emerges the enormous flower, reddish in color but dotted with white. Those flowers do not have a good scent; in fact, they give off an unpleasant odor like that given off by rotting fish […] If our compatriots could transport it to Java or Sumatra, they would be capable of renewing the madness of the famous black tulip.”

As Paolo Ciampi observes in I due viaggiatore. Alla scoperta del mondo con Odoardo Beccari ed Emilio Salgari (Polistampa, 2010), for once Salgari quotes poor Beccari, making numerous errors, starting with the name of the flower and the date of its discovery.

With the season of great explorations finally over, Beccari embarked on a new phase that promised to be rich in rewards, such as his appointment as director of the collections and botanical garden of the Natural History Museum of Florence. But the same character that had allowed him to achieve great feats in the most challenging situations soon put him at odds with the academic community, and he resigned from his post. Forced by a lack of funds to also suspend publication of the magazine Malesia, which he had founded to disseminate reports of his research, he retreated to the vineyards of Bagno a Ripoli. It might seem like a sad and more than decorous epilogue, but an unexpected visit reignited the flame. In May 1897, Margaret Brooke, wife of Rajah Charles, showed up at Villa Beccari. Madame Brooke persuaded Odoardo to resume his pen for a volume summarizing his extraordinary knowledge of Borneo. Once the flow was rekindled, it was a deluge of information and experiences. In the forests of Borneo. Travels and Researches of a Naturalist was published in 1902, and runs to nearly seven hundred pages. It was a resounding success, translated into numerous languages, including English and Malay.

In those years, inspired also by the articles of Beccari and other explorers that he avidly consulted at home and in the Turin civic library, Salgari's novels continued to enjoy great success. Within the so-called "Indo-Malay cycle", for example, Le due tigri (1904) and Sandokan alla riscossa (1907) were published.

Odoardo Beccari passed away on October 25, 1920, at the age of seventy-seven. His last words concerned a book about his travels in New Guinea, which would be published posthumously. A brief article in the newspaper La Nazione commemorated him.

Emilio Salgari had already tragically interrupted his narrative journeys nine years earlier, on the morning of April 25, 1911. Exhausted by an unsustainable work schedule, financial difficulties, and grave family issues, he took his own life, leaving behind, among other things, a letter to his publishers. "To you who have enriched yourselves on my back, keeping me and my family in constant near-poverty or even worse, I ask only that in return for the earnings I have given you, you will consider my funeral. I bid you farewell by breaking my pen."

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto