White Sox, the Pope's team

Photo EPA, via Ansa

magazine

They are baseball's "weaks," but with one exceptional fan: Leo XIV. Redemption from an old scandal.

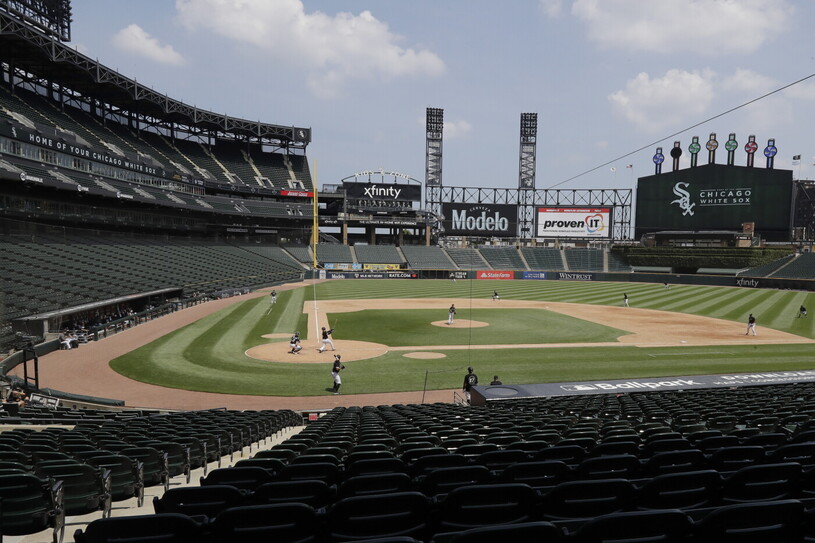

Pilgrimage sites around the world, whether spiritual or secular, are often unusual. Rural and remote areas suddenly become famous for Marian apparitions. Or small grocery stores suddenly become overrun thanks to Tripadvisor. But it's hard to imagine a more unusual pilgrimage destination than seat number 2, row 19, section 140 of Rate Field, a baseball stadium in Chicago that takes its name, far from legendary, from the low-interest mortgage company that sponsors the local team: the White Sox . Legendary, yes, the "white socks" who for 125 years have been the joy and, above all, the pain of Chicago's South Side, the most working-class, proletarian, and immigrant- and minority-rich part of the Illinois city .

One of the things that makes the White Sox iconic, making them a fixture in popular culture and a favorite of entertainment stars, is what the more benevolent call the team's "curse," while the more cynical define it differently: "They're bad." Whatever the truth, what is certain is that the Chicago team's history is marked by rare victories, a gigantic scandal, and many, many years of drought .

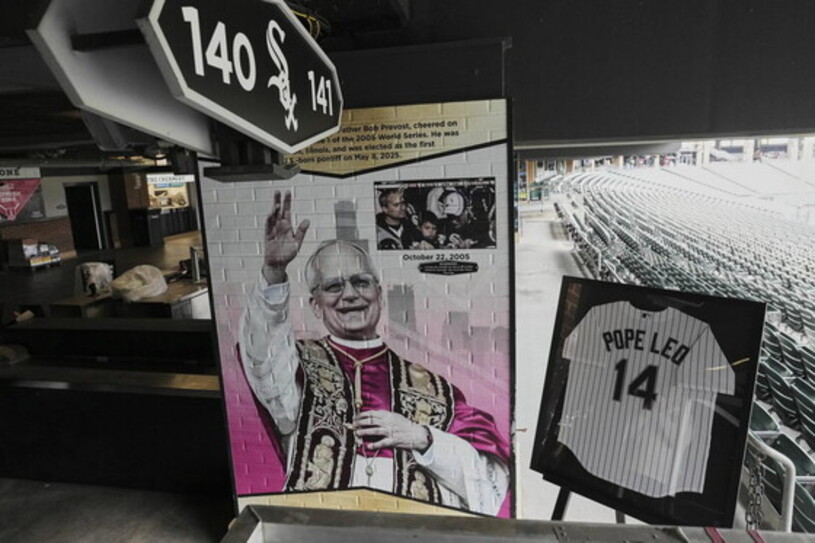

After winning the World Series in 1906 and 1917 (the seven-game final that seals the two national baseball championships), the White Sox failed to repeat the feat for 88 years . Then, twenty years ago, suddenly, the miracle: a title won in 2005 after dominating the season, a triumph that, two decades later, is still recounted to children with legendary tones. And in recent months, it has taken on new characteristics and a touch of mysticism, mixed with a bit of American sports kitsch. Because in Game 1 of the final series against the Houston Astros, sitting in seat number 2 in row 19, section 140, the cameras that evening in 2005 captured a priest dressed in a white and black Sox jersey. Back then, he was known as Father Bob Prevost; today, he is Pope Leo XIV , and his place in the stadium from twenty years ago has become a sort of secular tabernacle and a point of attraction for those who go to Rate Field to watch the Sox play. The sports club has even dedicated a mural to “Pope Leo,” as Americans call him (or “Da Pope,” as the locals call him in Chicago slang), and the pontiff has reciprocated the affection several times in these first months in the Vatican, appearing in a South Side team cap and signing various team jerseys . Including the number 14, which was ceremonially presented a week ago to the hero of the 2005 team, Paul Konerko, who played with the number he now shares with the Pope (the names “Konerko” and “Pope Leo” are written together on the back of the jersey).

Thirty thousand people gathered at Chicago Stadium a month ago for a mass in honor of Leo XIV and to listen to his video message, confirming the excitement that accompanies the discovery of having such a significant fan, one who surpassed even the other famous South Side resident, until now considered the biggest Sox fan: Barack Obama. He was also there, then a young senator from Illinois, that night of Game 1 in 2005, probably the only sporting event in history in which a future Pope and a future President of the United States participated simultaneously. And in Chicago, the question is now being asked how "providential" their presence was in helping one of the most beloved and unfortunate teams in baseball history win the title, which, after that moment of light twenty years ago, has returned to its usual shadow. Last year, the White Sox set a record in the most American of American sports, losing 121 games—a record they snatched from the Queens Mets, a record they had held since 1962. This year, things aren't going any better: they're last in the American League Central standings, and at their current pace, they'll finish with 108 losses, the third season in a row and the fourth in the last eight years in which the Sox have broken the shameful threshold of losing 100 games. A debacle that fans largely attribute to the decisions of Jerry Reinsdorf, the billionaire who has owned the Chicago Bulls and the White Sox for forty years and who now seems ready to sell the team and exit Major League Baseball (MLB, the league that brings together American professional teams).

The pilgrims visiting the mural and the chair that now make the White Sox "the Pope's team" hope this is the right time for a turning point. But they're accustomed to rooting for a team that historically requires a sporting faith that certainly can't be based on the paltry results achieved since the White Sox were brought to Chicago in 1900 by Charles Comiskey, the legendary founder of a club that has shaped, for better or worse, the history of American baseball. The team was born in Sioux City, Iowa, then moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, and finally landed on the South Side. Rivalry immediately erupted with their North Side cousins, the Chicago Cubs, another team with a record of victories: after winning the 1907 and 1908 World Series, they went without a win until the 2016 season.

In the first twenty years of the last century, with the Cubs and the White Sox, Chicago dominated American sports with a superiority that would not be seen again in the city until the 1990s , the years of the basketball dictatorship of the Bulls of Michael Jordan and Phil Jackson . Then came the shocking event that changed everything.

In 1917, the Sox won the title by beating the New York Giants with a team that at the time seemed invincible. Two years later, in 1919, they were again in the finals, this time against the Cincinnati Reds. The superstar was outfielder “Shoeless Joe” Jackson, who had been leading the Sox from victory to victory for years and seemed poised for another triumph. But that year, there were strong disagreements between the players and Comiskey, who paid them little and certainly had a bad temper. Countless theories have circulated over the years about what happened in that World Series. The fact is that the Sox lost to the Reds, and eight Chicago players, including Jackson, were shortly thereafter accused of intentionally causing the defeat, thanks to an underground betting ring run by local organized crime, which already controlled half the city (1919 was also the year in which a figure destined to dominate Chicago for years arrived from New York: Al Capone).

“Shoeless Joe” and others among those eight spent the rest of their lives trying to prove their innocence, but the league took a hard line, banning them for life, and thus ending the Sox's dominance, paving the way for an eighty-eight-year wait before winning the World Series again in 2005. It's no surprise that that final was such a unique and significant event that it even prompted Father Prevost to return to Chicago to attend a game of his favorite team, during his years constantly traveling the world as Prior General of the Augustinian order. 2005 marked, in a way, the end of the “Black Sox curse,” as the players of that legendary and controversial 1919 team were nicknamed.

The Black Sox scandal has long been a defining moment in American popular culture . Dozens of books have been dedicated to the story of “Shoeless Joe” and his teammates, including a reference in Francis Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby.” Hollywood has also fallen in love with the story several times. After a couple of references to the scandal in Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather,” the first film entirely dedicated to the case, John Sayles’ “Eight Men Out,” was released in 1988. But the most famous film about the ill-fated Chicago team came a year later: “Field of Dreams,” an unusual modern fairy tale about farmer Kevin Costner who builds a baseball field in the middle of nowhere among the cornfields of Iowa, to bring the ghost of “Shoeless Joe” (Ray Liotta) back to the game and please a writer in love with that team (James Earl Jones) . And since fairy tales often have a happy ending, two months ago the league decided to remove Jackson from baseball's blacklist, acknowledging that he played a marginal, if not even nonexistent, role in the 1919 scandal. The former champion is now eligible for the Hall of Fame, the baseball hall of fame that annually attracts thousands of fans to Cooperstown, the town in upstate New York where legend has it the sport of bats, balls, and gloves was invented and which now houses the celebrity museum. Under league procedures, "Shoeless Joe" could be added to the list of baseball greats in 2028, thus erasing his black legend.

A legend that nonetheless contributed to the myth of the Sox and that undoubtedly accompanied the childhood and adolescence of Robert Prevost and his brothers on the South Side in the 1960s and 1970s. When the White Sox were famous for never winning, their fans still packed Comiskey Park, the stadium of the time that was the dream home of the young Prevosts, later demolished in 1991. Who knows if one day the Pope will recount the effect growing up as one of the "Comiskey Boys" had on his education and character, the kids at the Sox stadium who began each season hoping for a victory for their favorite team, only to be invariably disappointed. A fate they shared with their rivals the Cubs, but especially with the Boston Red Sox. The latter were also long infamous for a curse, the so-called "Curse of the Bambino" because it was linked to the figure of the great champion Babe Ruth.

In 1918, the Red Sox won the World Series, and the following year, while the Chicago White Sox were embroiled in scandal, the Boston team decided to sell their star player to the rival New York Yankees. It was the beginning of the New York team's successful dynasty, led by Babe Ruth, while Boston was embarking on a long, lean season that ended only with the 2004 World Series victory. A title drought that lasted as long as the White Sox's, but unlike Chicago, it transformed into the start of a positive cycle in Boston. The Red Sox won again in 2007, 2013 and 2018 and have become one of the strongest teams, also thanks to the strategic choice of following the new baseball approach based on the analysis of data and statistics invented in 2002 by Oakland Athletics manager Billy Beane, the character played by Brad Pitt in the film “Moneyball” (the same approach that a student and admirer of Beane, Damien Comolli, now wants to bring to Juventus, where he has just become general manager).

In Chicago, however, they remained anchored to tradition; even redesigning the team's logo resulted in a return to the graphics and font of the early 20th-century Sox. The surprise was how much the fans loved this return to the past: Sox uniforms and caps quickly became fashionable across the country, worn by hip-hop stars like Dr. Dre and Eazy-E. A strange fate for a team that wins very little and carries with it the ancient stigma of a scandal, yet is "cool" and beloved by its colorful and ethnically diverse fanbase, far more than America can tolerate. And it can now boast of being able to count on the prayers of a special fan who has become Pope. Who knows, perhaps Chicago is ready for a new "dream man" fairy tale, and that after the end of the long Reinsdorf era, a season of success similar to that of the Boston red socks is on the horizon, even for the white socks. In the Vatican apartments, there's a superfan whose only white outfit is his socks, and he'll be ready to party.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto