Butterflies that look and buzz like wasps, or visual-acoustic mimicry

The wasp-tailed butterfly evolved to resemble a hornet to scare away predatory birds. It resembles the wasp not only in appearance, but also perfectly imitates the buzzing sounds it produces, which effectively discourages potential attackers - has been proven by a study by Dr. Marta Skowron Volponi from the Faculty of Biology, University of Białystok.

As the researcher has shown, butterflies from the family of clearwings are masters of mimicry - although they are completely defenseless against predators, they are strikingly similar to dangerous stinging insects: wasps, bees or hornets. Their transparent wings, yellow and black stripes on the abdomen and the way they fly make it easy to confuse them with the dangerous insect. However, to make their defense strategy even more effective, in the course of evolution they have also developed imitations of the sounds characteristic of their originals.

"Such an adaptive mechanism is a classic example of Batesian mimicry - a phenomenon in which a harmless species has become similar in the course of evolution to another species that has effective defence mechanisms, e.g. the ability to sting," the entomologist from the University of Białystok told PAP.

She explained that the vast majority of observations and studies on mimicry focus on morphological similarities. In the meantime, she and her team decided to see if mimicry could extend to other senses, including hearing. The idea for the study came to her in the field when one of these butterflies flew very close to her ear. "I heard it buzzing just like a bee. It was a revelation for me," she recalled.

The results of the research, conducted in collaboration with the University of Turin and the University of Florence, were published by the scientist in the journal Ecology .

To confirm whether the peepholes really do imitate not only the appearance but also the sounds of stinging insects, the authors designed an innovative method of recording insects in flight – the buzzOmeter system, recently described in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution (https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14224). "We wanted to be able to record them in their natural environment, without immobilizing them, because then the insect changes the sounds it makes," she explained.

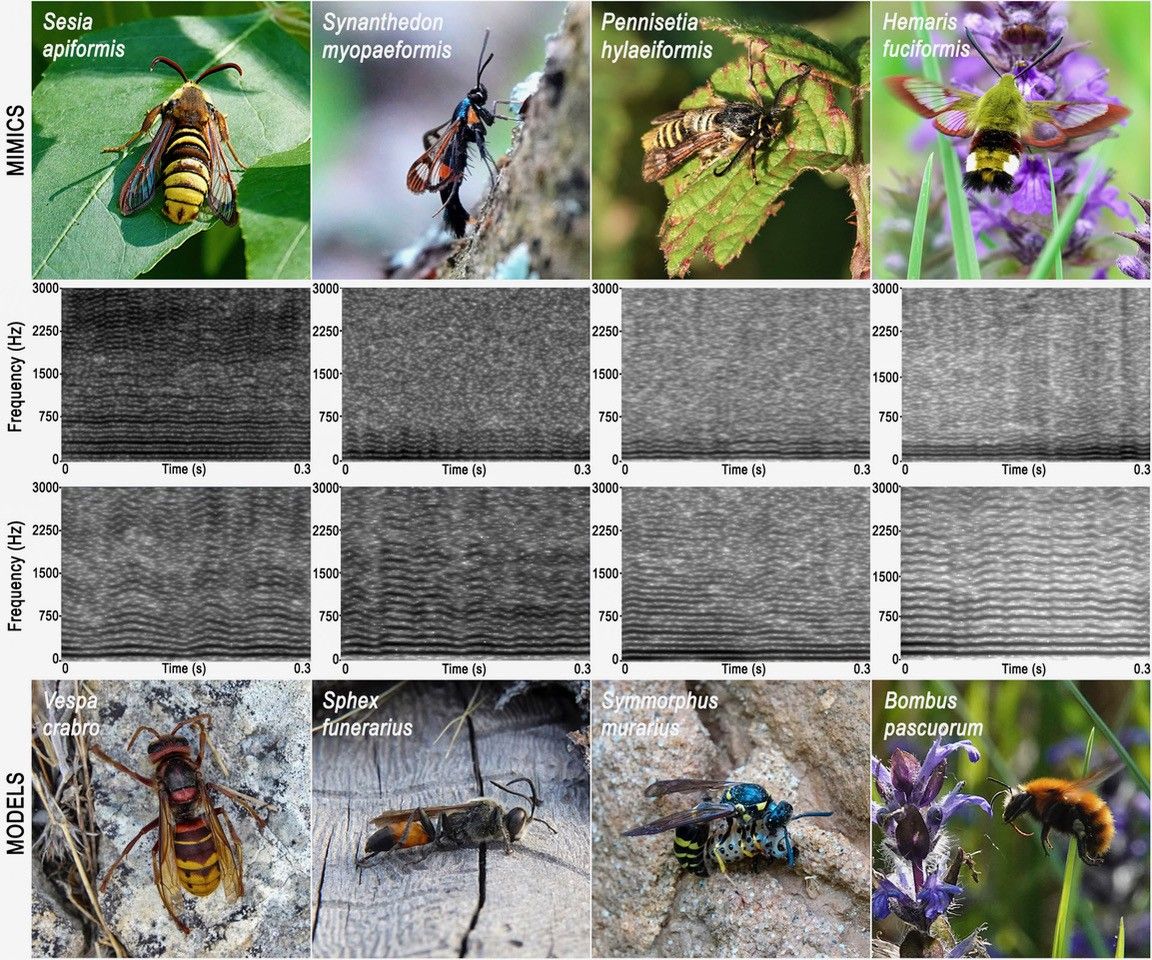

Using this tool, the researchers recorded sounds made by eight species of insects, specifically four pairs consisting of a "mimic" (a hawk moth or hawk moth) and its mimic model (a stinging moth). Additional recordings, acting as a control, came from a hawk moth that does not exhibit visual mimicry but also buzzes in flight.

"Analysis of acoustic parameters showed that in the two tested pairs the sounds were similar enough to speak of acoustic mimicry. The Sesia apiformis turned out to be particularly spectacular, it looks like a hornet and - as we have shown - also buzzes almost identically to a hornet," said the biologist.

The key objective of the study was to check whether the identified mimicry works in a confrontation with a real predator, and therefore whether it is effective. And this is where the challenge arose. "Most studies involving birds are conducted in captivity. We really wanted to avoid this, because birds in aviaries change their behavior, and we wanted natural interaction," the researcher noted. Ultimately, the choice fell on robins - a territorial, omnivorous species that can be easily accustomed to using feeders in the field.

The experiment lasted two seasons and involved 21 wild individuals. Scientists presented each bird with a different species of insect - once a butterfly, once its mimicry model, while playing the corresponding buzzing sound from a speaker placed in a feeder.

"The bird had the full experience: it saw the insect and heard its sound," emphasised Dr. Skowron Volponi.

All experiments were videotaped and analysed, during which the scientists measured various behaviours of the robins, including how long it took them to approach the feeder and how many tasty larvae they ate from the vessel containing the test insect.

"It turned out that the robins were most afraid of the hornet and the wasp-eater. Their reactions were almost identical to both species. It was clear that the bird was clearly hesitant about whether to approach the feeder or not, and it ate a significantly smaller number of larvae. This means that in the robin's assessment, approaching the wasp-eater carries a similar risk as interacting with the hornet," concluded Dr. Skowron Volponi.

In the case of the remaining pairs - for example, smaller hymenoptera and the mimics of them - the robins reacted neutrally. "This did not surprise us, because if the bird was not afraid of the small hymenoptera, there was no reason for it to be afraid of its mimic. But most importantly, the reaction to the model and the mimic in each pair was always similar," the biologist noted.

She added that this does not mean that mimicry is pointless in the case of these butterflies. "They may not be frightening to robins, but they were probably selectively pressured by other predators that we have not yet identified; perhaps lizards, mantises or spiders," she explained.

The author of the study admitted that the peepers - although some of their species are relatively common in Poland - are rarely observed. "Even experienced entomologists often say that they have never seen a peeper. Most of them live for a short time, some do not eat as adults, and their activity is limited to a short flight season. And on top of that, they are usually simply confused with wasps," she said. (PAP)

Science in Poland, Katarzyna Czechowicz

drip/ bar/

naukawpolsce.pl