There is a good case for classifying criminal networks as terrorists, says American professor

He was a U.S. government representative for the promotion of human rights during the Ronald Reagan era, traveling the world on behalf of USAID (the U.S. government agency for international development) to encourage political reforms. He also worked at the State Department (equivalent to the Itamaraty) investigating war crimes.

After a long career at the National Defense University, linked to the Department of Defense, he became one of the world's leading experts on international criminal networks, participating in studies that point to the phenomenon of criminal convergence — when groups specialized in completely different crimes, from terrorism to drug trafficking, begin to collaborate and strengthen each other.

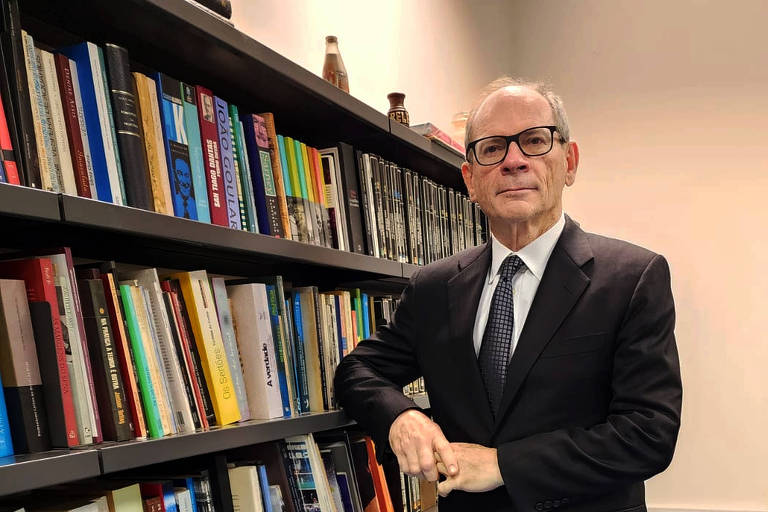

Today, Professor Michael Miclaucic, 71, is the coordinator of the Oswaldo Aranha Chair in Security and Defense, a USP study center dedicated to research on these topics and dialogue between academia and other stakeholders. About nine months ago, when he stopped working for the US government, he was able to break a 42-year fast in which he could not give interviews. On Monday (23), he spoke to Folha .

Focusing on criminal convergence in the Americas, he supports flexibility in the way governments classify criminal organizations as a way to combat growing criminal flexibility.

In 2013, you wrote that the United States was taking important steps to combat transnational organized crime. How would you assess the past 12 years in this regard? Unfortunately, I cannot say that there has been much progress. There has been a persistent refusal to recognize the scale of demand from transnational organized crime as a significant factor. Authorities still too often focus exclusively on the criminals and dismiss the customers as collateral damage.

In some countries and regions, transnational organized crime has become a political force and we have seen cases of criminal capture of the state, which is, I would say, something relatively new. I have to admit and acknowledge that in the last 12 years, with no disrespect to those who are working tirelessly to combat transnational organized crime, progress in general has not been evident.

In your book, in the article you wrote with Moisés Naím, you say that it is an illusion to think that illicit behavior is an aberration and that the people involved are deviants. You also say that 'every day millions of people around the world wake up, go to work and bring bread to their families, all thanks to doing something that we label as criminal'. In these circumstances, is it a mistake to classify some activities as criminal? To be clear, what we wrote was not intended to condone any criminal activity, but was an acknowledgement that criminal activity and complicity are not radically unusual behaviors and should be understood as quite common, even if unjustifiable. But your question raises deeper questions about how we define crime.

Most of us, I believe, would agree that human trafficking is unacceptable and rightly categorized as a criminal activity. Just 25 years ago, marijuana use was considered a crime throughout the United States. And now it is legal in 40 of the 50 states for medicinal use and in 24 states for recreational use. So what we define as a crime needs to evolve along with social tolerances and, for that matter, with the evolving technology and economic environment.

But what about the cultivation of coca or poppy by many families in Central America or Afghanistan? Both plants can have uses other than illicit drugs. Weren't you talking about that? There are two possible ways to look at this issue. One is that the product itself can have multiple uses, like marijuana, which can be used for medicinal purposes, or precursor chemicals manufactured in China that have dual-use applications. The other aspect is: can we tolerate the harvesting of marijuana, poppy or coca for economic purposes by people who have no viable economic alternatives? And this is a very deep sociopolitical and economic issue, for which countries need to develop national strategies.

Why do you think there is a lack of discussion about demand? Is it possible to combat international drug trafficking and criminal networks without changing the way we regulate illegal substances? I don't think it's just about regulation. This is not a problem of local organizations, it's a problem of networks of organizations that are transnational. Even Brazilian organizations, like the PCC [Primeiro Comando da Capital] or the CV [Comando Vermelho], are international organizations. We certainly know that the Sinaloa cartel is a transnational organization, the 'Ndrangheta, the Italian mafia, is an international organization.

Clearly regulatory regimes have failed to keep pace with chemical innovation, which, with just a change of a single element in a compound, can transform a controlled and illegal drug into a previously undefined, uncontrolled and unregulated compound. Which suggests to me that a different approach is needed.

Again, no strategy that fails to recognize the demand for illegal goods and services provided by organized criminal groups will succeed. There are a variety of recommended ways to address the demand problem. Public education can be successful. No one I know of has found the perfect solution to this problem. But there is evidence of success in some places, and this should be collected, closely examined, and experimented with.

Do you agree with the classification of the Tren de Aragua , La Mara Salvatrucha, and the Mexican drug cartels as terrorist organizations ? Let me begin with a caveat. I would not offer any recommendations to Brazilian law enforcement agencies because they have a lot of experience in this fight. One could argue that since drug cartels often use the same communication and financial channels as terrorist organizations, as well as some—if not all—of the same violent battlefield tactics, techniques, and procedures, it doesn’t really matter what their motivation is. Or at least in some respects, it doesn’t matter what their motivation is. None of these organizations are pure and monolithic. There are certainly individuals and people in terrorist organizations who are in it for the money.

A terrorist organization like the Islamic State has become a vast criminal economic enterprise. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia has become a major drug trafficking organization. There are cases in the Philippines where organizations at one point had ideological motivations, but those motivations have dissipated and they are simply in it for the money. On the other hand, there are some criminal organizations that, although they may not embrace religious objectives, are embracing political objectives and want political control of territories, of squares, of cities, urban centers, and even run candidates to support their views. And that is what I call criminal capture.

When criminal organizations are running their own candidates for office and winning and growing, representing people in government but with criminal motivations behind them, that is highly problematic. So does it make sense to classify criminal organizations as terrorist organizations? One size fits all [i.e. each case is unique]. There is certainly a good debate to be had about this. If treating them as terrorist organizations gives law enforcement a broader set of authorities and tools to combat this 'cancer', then that is certainly a good argument.

Isn't there a problem with the sovereignty of countries, given what U.S. law allows when it comes to terrorist organizations? Yes, there is a problem there, but I believe that the solution is not indecipherable. U.S. law now designates, I think, about half a dozen cartels, drug trafficking organizations as terrorist organizations. What the law does not say is that the United States can invade Mexico to fight the drug war on Mexican soil. It does provide law enforcement agencies in the United States with a broader range of tools to fight the drug war, if we can call it a war. But I believe that in order for us to be successful, these tools need to be used in close consultation with our neighbors, partners and allies, including Mexico, and with full respect for the sovereignty of our neighbor.

What would you say is the most important issue in combating international organized crime in the world today? The world has been preoccupied with other things. Frankly, that’s part of the reason we haven’t made progress globally. The world has been preoccupied with the global war on terror. Then it was preoccupied with the rise of China, then it was Ukraine, now it’s Gaza and Iran. The world has never really focused on this challenge in a coordinated way outside of international organizations, multilateral organizations and nongovernmental organizations — which really have very little power. So anything we can do to promote public education about this is a public good.

Has that changed? Are governments paying attention to the problem of organized crime? In 1999, the then head of the IMF, Michel Camdessus, said that the total value of the illicit market was 5% of global GDP. Today that would be $5 trillion, which is larger than the economy of most states, except for a very small group. If people realized what $5 trillion can buy—in terms of weapons of mass destruction, in terms of bribery, in terms of the best lawyers, militias, accountants and technologists—then yes, there could be progress. We have made progress against slavery around the world. It was not that many centuries ago that slavery was common. Today it is politically unacceptable. Apartheid was acceptable 100 years ago. It is no longer acceptable. I think this problem could be effectively addressed. I'm just not sure when.

Michael Miklaucic

A graduate of the University of California, he holds a master's degree in economics from the London School of Economics. He served under four American presidents (Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush) in various capacities. He is currently a professor at the University of Chicago and coordinator of the Oswaldo Aranha Chair in Security and Defense at USP.

uol