The Left and Emotions | Breaking up with love

"Where are you going swimming tomorrow?" – an unusual question to ask an author at a reading. But that's exactly what the audience at the Volksbühne wants to know from Constance Debré, who is there to talk about her novel "Love Me Tender." Will she, like her narrator, be swimming her two-kilometer crawl somewhere in Berlin that morning? How great are the similarities between the author and the narrator of her novels? Where can one meet her for a Marlboro Light? Debré doesn't answer the questions, but that doesn't diminish the fascination she exerts on her readers. Quite the opposite. They buy her books, including the perfume "Habit Rouge," which the narrator wears. On the website "Goodreads," someone comments on "Love Me Tender," calling it "my bible," while another writes "Feminist must-read!"

And what is this book about? On the first page, the narrator makes it clear: "I wonder what they're hiding from us, what they actually want from us with this grand narrative of love." It's about love, then, which becomes problematic when it's packaged too broadly. Debré's novels are in search of something else: the self, freedom, desire, independence. To do this, love must be removed from the path or at least radically transformed. "When do we put an end to love? Why doesn't that work?" are the questions that preoccupy Debré's narrator—and apparently her readers as well.

The old story of loveThat literature tells us something about love is an old story that nevertheless remains ever new. Not only is loving and—albeit to a lesser extent—being loved still one of the most popular subjects of literary texts, but love itself also takes on forms borrowed from literature. It follows a suspenseful arc, creates unexpected connections, finds symbolic images for feelings, and builds up to dramatic scenes. This means that the relationship between love and literature is a reciprocal one: social norms and practices of loving are reflected in literary texts. At the same time, literary depictions of love fuel expectations, solidify forms of feeling, or undermine them.

In her famous essay "Bittersweet Eros" (1986), Anne Carson, based on a reading of the ancient poet Sappho, describes how love scripts unfold in a triangular pattern. There is always the loving subject, the beloved object, and the obstacle between the two. The way this tension is shaped is subject to historical change – and provides us with insight into the function of love in specific social contexts. Literary scholars often cite Goethe's "The Sorrows of Young Werther" as the starting point of a modern emotional culture that developed in 18th-century Europe. The bestseller at the time was also so well received because its love script combined intense, tragic love with authenticity, a thirst for freedom, and naturalness – ideals that contributed to the development of a bourgeois self-image.

Two hundred years later, in his Glossary of Love, the alphabetically ordered collection "Fragments of a Language of Love," Roland Barthes once again chose Goethe's "Werther" as a reference point for his writing about love. Against the backdrop of contemporary schools of thought, psychoanalysis, and deconstruction, the "Fragments" emphasize the autonomy and physicality of language. In keeping with the zeitgeist of the 1960s and 70s, love is interwoven here with a self that is placeless, changeable, and guided by desire. And it is precisely this historical lineage that Constance Debré also joins. In 2007, she wrote her own version of the "Fragments," the abcdarium "Manuel pratique de l'idéal," inspired by Roland Barthes and George Perec. Shortly thereafter, she became famous with "Play Boy," "Love Me Tender," and "Name." She herself has become the author of internationally successful, widely discussed, and award-winning novels about love. But which love scripts do Debré's texts continue, and what contemporary needs and collective fantasies do they point to?

Homosexuality as a vacation ?Although the individual texts stand alone, all three novels tell episodes in the life of a mid-40s, well-to-do Parisian lawyer who leaves her marriage and career behind to devote herself entirely to writing and relationships with women. In connection with this radical break, the novels revolve around the question of how loving and being loved become narratives that constrain or liberate the self.

First, there's marriage—heterosexual, monogamous, boring. In "Play Boy," the narrator separates from her husband after 20 years; in "Love Me Tender," the same characters are embroiled in a bitter custody battle. Familial love, like that between the narrator and her father, faded many years ago, as is stated in "Name." Love for one's own son is more complicated: the narrator suffers from his absence and rejection until she finally learns to live without him. This process is both mourning and recovery, ultimately compared to recovering from the flu.

The narrator finds herself by breaking away from relationships, leading a nomadic life with little money but plenty of time to go swimming, write, roam the city as a dandy—and have relationships with women. With them, she experiences a third kind of love: Eros, sexual desire. Initially shy and exploratory, then with a previously unimaginable lust and desire, she experiences a coming out, or rather a return to her homosexuality, which was actually already clear as a child. Eros sometimes appears as genuine love, but repeatedly also as its antipole, referred to as "bedtime," "sex," or "fuck." The relationships are not aimed at permanence or commitment. The narrator is bored when the women she sleeps with talk about their families, wish for a steady relationship, "a vacation or an evening at a nice restaurant," or even "an apartment, a dog, children." The narrator rejects these aspects of love because they are associated with possessiveness, routines, and the creation of normality. "I thought homosexuality was about that too," Debré writes.

Inspired by queer artistic positions such as those of Kathy Acker, Hervé Guibert, and Oscar Wilde, loving, alongside writing, is a pleasurable and radical practice of self-realization: "I love for the first time because I love sex without anything, without anything that could reassure or oblige, without love, without talk, without history, without habit." In the image of love that Debré paints in her novels, the ideal of authenticity, spontaneity, and intensity of a "Werther" reappears. As in Barthes, this ideal is linked to the aesthetic experience of the self. The narrator cultivates a bohemian habitus, which includes cigarettes, a leather jacket, tattoos, shaved hair, lots of sex, and a contempt for all frills, be they in furnishings or social interactions. She sees herself as a "lonely cowboy."

Homosexuality, the artist's existence, and deviance intertwine. Whether it's the narrator breaking up with women as soon as they speak of love, giving up her secure income as a lawyer to write, or stealing from the supermarket "for the beauty of the gesture": her sexual relationships with women help her undergo a transformation that leads her out of the confines of societal expectations and into the open. "For me, homosexuality simply means a vacation from everything. Yes, that's it: the big vacation, something as vast as the sea, without a horizon, nothing conclusive or defining."

Heteropessimistic practiceEnding a marriage, homosexuality as a great vacation, concise literary-sociological autofictions à la Didier Eribon, Édouard Louis, or Annie Ernaux: If we consider "Love Me Tender," "Play Boy," and "Name" in the context of current discourses on love, it becomes clear that the Debré phenomenon stands for "radical agency" (Die Zeit) and is therefore met with such a strong resonance in the literary world. Debré no longer compromises when it comes to matters of love. Readers speak of his ruthlessness and a detachment from obligations that impresses them. The fantasies of independence, both emotional and financial, are attractive. Who doesn't want the freedom to write, swim, or fuck? Or at least dream about it? Here, literature reveals itself as a space of possibility and as a substitute for gratification.

Undeniably, her public persona also plays a role in the broad reception of Debré's books: Coming from a scandal-ridden family that produced politicians, doctors, lawyers, and models, Debré's literary and personal transformation into a butch—with a classic look of leather jacket or pinstriped suit—makes her an enfant terrible of the French upper class. This feeds into fantasies of escape and is provocative. But Debré is not only a hype in the mainstream, but especially in queer-feminist circles, as she ties in with the feminist tradition of wanting to finally put an end to familial and marital love, these Trojan horses of the patriarchy.

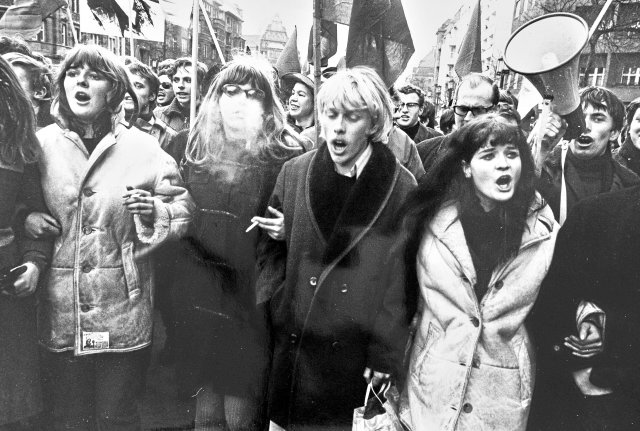

The enthusiasm for Debré is just one of many signs that the feminist struggle against and with heterosexual love continues, even taking on new forms. Since 2019, the term "heteropessimism" has been circulating in queer feminist circles. This feeling was named by Asa Seresin in his essay of the same name in the online magazine "The New Inquiry."

Heteropessimists feel "regret, shame, and helplessness" in the face of their own heterosexual experiences. But instead of ending love, they come to terms with resignation. This allows them to distance themselves from their own desires without challenging the status quo. "Changing the conditions of 'straight culture' collectively is not within the purview of heteropessimism," Seresin criticizes. Women* who practice abstinence from heterosexual sex and dating—at least for a time—are somewhat more active. Comedian Hope Wooddard calls "boysober" a strategy that involves reflecting on oneself. Wooddard emphasizes, however, that those who live "boysober" by no means say goodbye to heterosexual love: "I love thinking about love and how to love better."

Beyond the couple relationshipFor actress Julia Fox, however, who has been flaunting her celibacy on social media for more than two years, there is no way back to partnership or even marriage. Instead, Fox celebrates friendships as a chosen family. In this way, she apparently thinks about love in a similar way to Katja Kullmann, for example, who, in her biographical non-fiction book "Die Singuläre Frau" (2022), finds connection and intimacy not in the nuclear family, but in friendship, neighborliness, and "random interpersonal relationships." For Ole Liebl, too, the future of better coexistence lies in friendships, as he describes in "Freunde lieben" (2024). And Andrea Newerla ushers in "Das Ende des Romantikdiktats" (2023), advocating instead for forms of closeness and love outside of couple relationships.

How do loving and being loved become narratives that constrain or liberate the self?

-

All of these books reflect what is already everyday life for some, and still ideal for others: families beyond partnerships, based on the co-parenting model. Or relationships that are open or involve more than just two people. How these can succeed ethically so that everyone feels "polysecure" is explained in the eponymous guidebook and bestseller by Jessica Fern (2020). What all of these different approaches to love have in common is that they are transformative but also integrative: Instead of simply abolishing the old heterosexual marriage and exposing societal norms of love as coercion and illusion, their advocates strive for a different, queer*feminist, empowering love. A love that creates solidarity, equality, and a good life for all. Feelings form the basis for this, and these—both pleasant and unpleasant—must be reflected upon, named, and communicated, brought into being with new terms, and thus made tangible and communicable. In short: feelings must be processed in order to transform and integrate.

With this targeted emotional work, queer feminism reflects a more general social trend toward emotionalization and therapeuticization, while simultaneously shaping it from the margins in an emotionally avant-garde way. This gives rise to sociological phenomena that many people are already familiar with in their everyday lives: therapy, couples therapy, emotional circles and awareness teams, digital emotional tracking, discussions about vulnerability and sensitivity, mindfulness diaries, and listening to oneself. Feelings and their evaluation as legitimate or illegitimate are part of these practices and often a benchmark for a successful relationship. This observation is not meant to be normative: it is a sociological observation that feelings are becoming the subject of explicit debate more than before, and that they are gaining significance in both private and public spheres—whether this is good or bad is unclear.

A vacation from your feelings?

And Debré? How does the lonely cowboy relate to mindfulness? The narrator of the novel trilogy, in any case, doesn't step out of bourgeois love to enter somewhere else. That doesn't interest her, the author explains at a reading when asked about the LGBTQIA+ community. She prefers to remain alone. In Debré's trilogy, love is radically transformative on an individual level, but it isn't integrative. What others do and don't do is of no concern to the narrator. Thus, the books don't fit at all into the political project that we otherwise encounter as ideals in queer*feminist (self-help) literature, in activism, and in queer realities of life. Debré's love script is a departure from this; it is disintegrative. What she herself admits in »Love Me Tender«: »I don't fight, I'm not part of any community, I have no elective affinities.« And she adds: »Of course we would have anarchy if everyone lived like me« – whereby by anarchy she seems to mean something like chaos.

Why does the author nevertheless exert such a fascination on the queer-feminist community? Literature must serve a different function here than serving as a model for real life. Because, in this context, the life of Debré's narrator cannot be a desired goal—it remains unattainable, at least for most. Only a few can afford to simply leave paid work because they are secure thanks to a well-known name and legal training. And what does a departure from models of solidarity look like when, like many women and queers, you perform care and support work?

Thus, the lonely cowboy becomes a compensatory figure. For Debré's narrator, he is, on the one hand, a role she seeks refuge in because society punishes her for the way she shapes her life and desires. Her ex-husband accuses her of pedophilia, and the legal system intervenes, temporarily depriving her of custody of her son. On the other hand, the cowboy projects a kind of freedom that is attractive: free from the sentimentality, softness, and desire for family and romance that the cowboy, in typical macho fashion, locates in (other) women, allowing him to focus entirely on himself and his own needs.

Radical exit fantasiesDebré's narrator is not like other girls . She rejects emotional labor, the queer*feminist processes that are supposed to make love fairer for everyone. "Play Boy," "Love Me Tender," and "Name" tell of radical fantasies of exit, not just from paid work, family, and marriage, but also from emotional labor. And that resonates. In times when authoritarian capitalism is baring its teeth ever more openly, the strength to work with and on feelings is dwindling. Because yes, dealing with feelings is also work; it can be unevenly distributed and it can be exhausting, it can cost increasingly scarce resources like time and energy.

And so the Debré phenomenon could signal a weariness with the love practices and discourses of our time. With Debré's "cool intimacy" (Illouz), one can conserve energy that would otherwise be spent on relationship and emotional work, and take a "vacation from feelings"—from one's own and those of others. It might still be okay for someone to love oneself, but loving oneself is already too exhausting. The radical reflection on oneself creates independence and thus peace from the demands of the emotionally complex and uncontrollable situation that contemporary bourgeois love gives rise to. Debré's cool cowboy puts an end to this. As the last line of "Love Me Tender" says: "It's not all that complicated."

nd-aktuell