Antidepressants help the immune system fight cancer.

A family of antidepressant drugs could become the immune system's best ally in fighting cancer. According to a study published in the journal Cell , selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase the ability of the immune system's T cells to fight cancer and, therefore, tumor growth in various types of cancer, both in mice and in human tumor models.

"It turns out that SSRIs not only act as antidepressants, but also act on our T cells, even as they fight tumors," says Lili Yang, senior author of the new study and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at the University of California-UCLA .

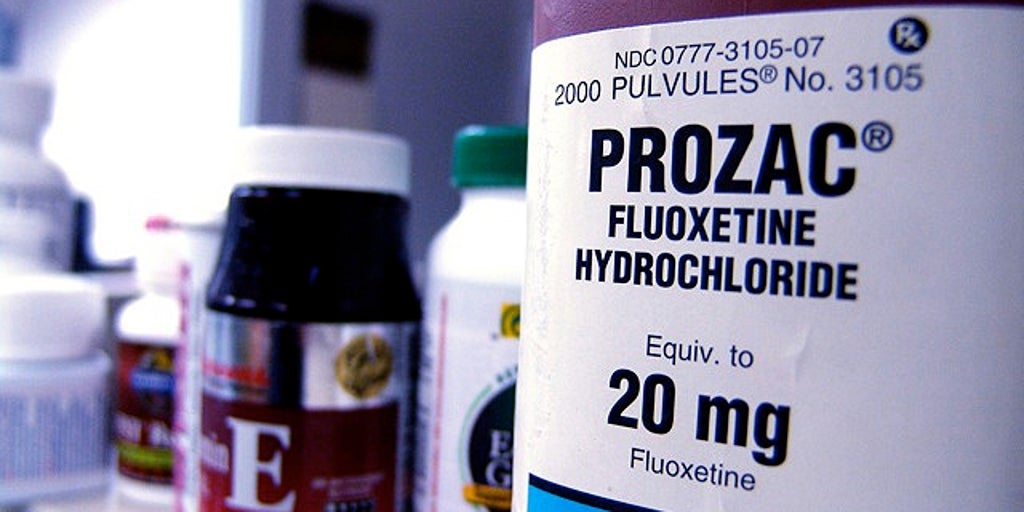

These drugs, such as Prozac and citalopram, have been used to treat depression for decades, so repurposing them for cancer would be much easier than developing an entirely new therapy, the researchers write.

The drugs increase levels of serotonin—the brain's " happiness hormone "—by blocking the activity of a protein called the serotonin transporter, or SERT.

But while serotonin is best known for its role in the brain, it also plays a crucial role in processes throughout the body, such as digestion, metabolism, and immune function.

Yang's team began investigating serotonin's role in fighting cancer after observing that immune cells isolated from tumors had higher levels of serotonin-regulating molecules. Initially, they focused on MAO-A, an enzyme that breaks down serotonin and other neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and dopamine.

In 2021, they reported that T cells produce MAO-A when they recognize tumors, making it harder for them to fight cancer. They found that treating mice with melanoma and colon cancer with MAO inhibitors (MAOIs)—the first class of antidepressant drugs ever invented—helped the T cells attack tumors more effectively.

However, since MAOIs pose safety concerns, including serious side effects and interactions with certain foods and medications, the team turned their attention to another serotonin-regulating molecule: SERT.

"Unlike MAO-A, which breaks down multiple neurotransmitters, SERT has a single function: to transport serotonin," explains Bo Li, first author of the study and a principal investigator in Yang's lab. "SERT was a particularly attractive target because the drugs that target it—SSRIs—are widely used with minimal side effects."

Researchers tested SSRIs in human and mouse tumor models representing melanoma, breast, prostate, colon, and bladder cancer. They found that SSRI treatment reduced the average tumor size by more than 50% and made cancer-fighting T cells, known as killer T cells, more effective at eliminating cancer cells.

“SSRIs made killer T cells happier in the otherwise oppressive tumor environment by increasing their access to serotonin signals, which reinvigorated them to fight and eliminate cancer cells,” Yang explains.

The team also investigated whether combining SSRIs with existing cancer therapies could improve treatment outcomes. They tested a combination of an SSRI and an anti-PD-1 antibody—a common immune checkpoint blockade (IBB) therapy—in mouse models of melanoma and colon cancer. IBB therapies block immune checkpoint molecules that normally suppress immune cell activity, allowing T cells to attack tumors more effectively.

The results were surprising : the combination significantly reduced tumor size in all treated mice and even achieved complete remission in some cases.

" Immune checkpoint blockers are effective in less than 25% of patients ," says James Elsten-Brown, co-author of the study. "If a safe and widely available drug like an SSRI could make these therapies more effective, it would have a huge impact."

To confirm these findings, the team will investigate whether real-world cancer patients taking SSRIs have better outcomes, especially those receiving ICB therapies.

"Given that about 20% of cancer patients take antidepressants, primarily SSRIs, we see a unique opportunity to study how these drugs might improve disease outcomes," Yang says.

abc