Who was Giacomo Brodolini, the socialist minister who invented the Workers' Statute

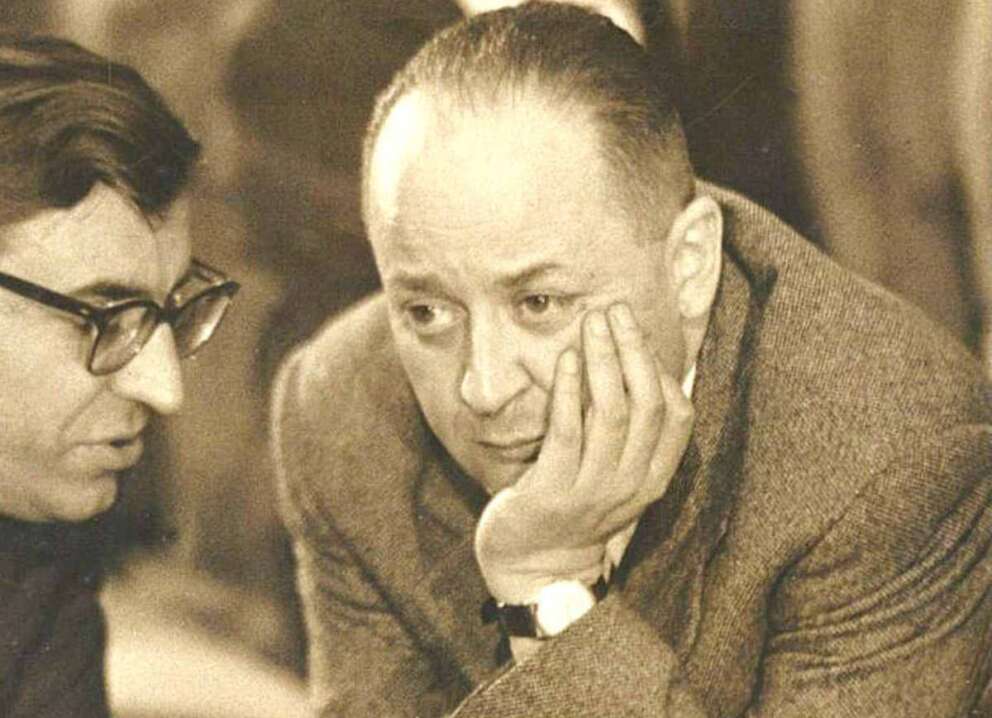

The portrait

Socialist leader of the Cgil, director of the Psi and Minister of Labor for about eight months between 1968 and 1969: a very short period in which an impressive number of reforms were conceived and implemented. Never "super partes", but on one side only: that of the workers

Gino Giugni often happened to be called the “ father of the Workers’ Statute ”, a title to which he reacted with amiable irony (“ Yes, I am the father ”). But even more often he remembered that the title did not belong to him, but to Giacomo Brodolini , partisan, socialist leader of the Cgil, director of the Psi and Minister of Labour for about eight months between 1968 and 1969. A very short time ended by his very early death, as he had been ill for some time, and in which an impressive number of reforms were conceived and implemented. Among them, precisely, the historic Statute, then brought to a favorable vote by the Chambers by his successor Donat Cattin.

Giugni would have also collaborated with the DC minister, but remained firm in attributing paternity to Brodolini because he had entered "directly into the merit of the Statute project" , and had " had the political initiative, which is what counts". Without forgetting that he had worked directly with his collaborators "indicating precise rules and the spirit of the Statute: putting an end to abuses through 'energetic support' " to a union rooted in companies and among workers. This, Giugni always recalls, but also his even more historic collaborator, the sociologist of labor Enzo Bartocci, up until the last meeting at the Hotel Rafael, "dramatic" because it took place immediately before Brodolini went to Switzerland to live the last days of his life with less suffering. In the Roman hotel, the closest collaborators still listen to the underlining of some fundamental principles that should never be derogated, some final variations and recommendations.

Giacomo Brodolini , born in Recanati in 1920, risks being forgotten, but some events of his life, some phrases he pronounced are also very famous. Like when he proclaims again, and more solemnly than ever, his commitment to the Statute from Avola, site of the last peasant massacre perpetrated by police forces still raised at the school of the Rocco code. Or like when on New Year's Eve, with little strength and without a voice, he spends the night with the workers fighting in a Roman factory. Rino Giuliani , an old trade unionist and militant, was there, and tells of the embarrassment of another important socialist leader, who in elegant clothes goes to the party and receives the greeting of Brodolini, very ill, in the cold, fighting with the workers. Also legendary are the phrases with which he describes his task as minister, a role that he does not at all believe he carries out " super partes ". He does not consider himself a socialist minister but rather a “socialist minister” , and declares that he interprets his role “ from one side only”, that of the workers. What ideology is behind all this? Simply democratic socialism, which does not conceive democracy except as that place in which the power gap between those who buy and those who sell work must be remedied. As is in the constitutional spirit of a “ Republic founded on work” and which “removes” the causes of inequality. That’s exactly it: it removes.

This is what public powers are for a democratic socialist, hence his declarations that do not arise from ideologies but from a deep culture of democratic rationality. The one according to which an economy grows more solidly without exploitation, as Paolo Sylos Labini ascertains, indicating in his own way the positive relationship between high wages and productivity, in Le Forze dello Sviluppo e del Declino, Rome-Bari, Laterza, 1984. And with him, also coherently realizing the principle, also the great economists of the Nordic union, such as Gösta Rehn and the more famous Rudolf Meidner. Brodolini's democratic socialism indicates, and then takes, the road of rationality and efficiency of an equal compromise after having precluded the road of exploitation (the natural one of capitalism, and its tendential vicious circles). Here, at that point the organized social classes will find themselves, they will clash, a solution will be dialectically generated, but only given the new democratic, socio-economic, legal premises, which in turn realize the constitutional ones. But in order for the social parties (behind which, as the Austrian social democratic leader Bruno Kreisky rightly asserted, classes always emerge) to be able to realize the dialectic from which political power can abstain, it was first necessary for Brodolini to be a “socialist minister”, “on one side only” . Because for a socialist democracy is certainly the equality of rights, but it is not truly such without class equality , and without (let it be clear) the dialectic, the clash and the compromise (which is never definitive harmony) that derive from it.

The success of the many strategic reforms of the “Brodolini Ministry” in a few months (including the pension reform, the one against wage cages , even the hint and project of health reform, as documented in my book) is made of this political culture: linear in conduct, complex in analysis, competent in solutions. Which is grafted onto the historical moment of union and worker protagonism. And which creates a condition rarely seen in the Italian scenario: a union at the head of a large movement, united as never before, and a “socialist minister” in government, with the appropriate technical and cultural tools. But also with the precise political will to synthesize the movement of the class and the coalition power of the PSI in government. After the grey years of the center-left governments led by Moro (1964-1968), in fact, Brodolini and the socialist current led by Francesco De Martino would not have allowed the return to government without precise guarantees, starting precisely with “ a socialist minister ” in Labor.

The Statute is the result of all this, well beyond the famous and for some infamous "article 18" . It created a union "inside" the workplace, according to a criterion that with a "technical" expression is called "promotional", with respect of course to the union. And then leaving the base of workers free to create the instruments of representation and basic negotiation, which were largely the Factory Councils (and later others), which the union-organization can be close to, in turn propellant (but not master) after the Statute had in turn guaranteed and pushed it. It is still to be told how Giacomo Brodolini became all this, starting from a family of the Recanati notability: his grandfather was a lawyer close to the Giolitti elite of the Marche, almost always later became fascist. And his father was certainly not an imposing figure, a scion who did not dislike fascism. Giacomo, on the other hand, belongs to the great generation born around 1920, the one that Il Duce would have raised as warriors, and which, given the unworthy fascist war, instead transformed itself into a partisan and passionately anti-fascist.

In the case of Brodolini, passing through the Partito d'Azione, but the choice of where to fight in the Resistance could be a coincidence, as another socialist trade unionist and partisan close to Brodolini repeated: Piero Boni. He became secretary of the PdA in the Marche, but then led a large part of it into the PSI. Brodolini showed at this point the talent of the workers' leader, in the FILLEA Cgil, and Morandi also wanted him in the party, which Morandi himself would rebuild in reality increasingly capable of autonomy after the negative experience of the Popular Front . The young socialist from the Marche would then lead the Cgil with Di Vittorio, who held him in high esteem, to the point of being convinced in '56 to denounce the Soviet invasion of Hungary . And then he would be the protagonist of the construction of the Centre-left, characterizing (together with the months between 1962 and 1963, full of other epochal reforms) the second great phase of implementation, precisely.

In short: this was Giacomo Brodolini . Born in the elite, he chose the working masses. Born in fascism, he chose the Resistance, democracy, the Republic. With great politicians and intellectuals, that is, with Francesco De Martino, a political leader and historian of Roman Law among the greatest ever, he decisively built the political proposal and, with wisdom, the solutions. He then chose, with Bartocci and Giugni, the skills, the technicians who were never technocrats, that is, the conjugators of science and socialism. This was Brodolini: authentic democracy, because there is no other, as we see today. And the best of our history.

l'Unità