'Dialysis? Never again' that's why Tugrul develops an artificial kidney and climbs 41 mountains

"Within a few years, your kidneys will stop working." That was the message Tugrul Irmak (30) received five years ago. Where many people would have taken it easy, he did the opposite: he went mountain climbing. Five years and a kidney transplant later, he is doing it again: 41 mountains of more than 4,000 meters high. To draw attention to kidney disease and the artificial kidney he is developing. "People think that kidney failure can be treated well with dialysis, but they have no idea what that demands of people."

When Tugrul was 11, he got an infection like everyone gets from time to time. "It must have been a respiratory infection or a stomach virus," he says, looking back. He recovered and went on with his life, until one morning, not long after, his urine was red with blood.

Autoimmune disease"I told my mother, who took me straight to the hospital. I remember thinking my parents' fears and concerns were overblown – I was an 11-year-old boy. But a few days later we were told that I had developed an autoimmune disease from the infection. There was a 50 per cent chance that my kidneys would fail within 20 years."

Even then, Tugrul had a similar reaction as he would later have: young as he was, he decided to get the most out of life. "It's a crazy message: there's a 50 percent chance that you'll get so sick that you can die from it, but also a 50 percent chance that you won't have any problems at all."

"Still, I had a strong feeling that I wouldn't grow old. I threw myself into school, wanted to get the best grades. I thought: maybe I can still contribute something. And it's probably also a cultural thing: I was born in Turkey and my parents have always found grades very important. I think that with this sword over my head, I wanted to make them proud more than ever."

With medication and regular – though painful – examinations in the hospital, things went well for a long time. Tugrul moved from England - where he had come to live from Turkey with his parents and sister at the age of 7 - to Delft, to do a PhD at the technical university.

But in 2021 – in the middle of the corona period – things went wrong. "My doctor told me that my kidney function had drastically reduced to 30 percent. On the scan I saw the scar tissue in my kidneys that had been caused by the disease and that my kidneys were no longer functioning properly. We still didn't know when my kidneys would stop working completely, but yes, that was scary to see."

Need for proof"But I also felt an enormous need to prove myself. When your body is sick, you can do two things: accept it, or deny it and show yourself that it's not that bad. I did the second. 'I'm going to climb mountains', I thought. I see that as the ultimate test of strength in which you are completely dependent on yourself."

Tugrul had climbed before, but never to this extent. He climbed several mountains with different climbing partners. "I had few complaints, so that went well. I did suffer a lot from gout, a form of rheumatism that is caused by crystallization of your urine, but I didn't let that stop me." The gout had developed because his kidneys could no longer properly remove waste products from his body. This led to severe cramps.

In May 2022, while climbing the Dom de Miage on the border of France, Italy and Switzerland with a friend, things went wrong. It started with a spot on his foot that hurt more than he said he had ever experienced. "On the way back, I couldn't put my shoes on anymore. It was just one spot, but it hurt so much. A few days later, my fingers started to cramp, and then my legs. My climbing partner tried to straighten them, I couldn't do it myself. But he also had a lot of trouble."

OverconfidenceStill, they continued, once the cramps had subsided. "Overconfidence, I think," he says now. "Not wanting to accept that I was ill." Later, when he was driving to Belgium, he got such a headache that he had to pull over. Migraine, he thought. The heat, the family doctor thought.

It was his friends who had to convince him that his complaints could be serious. Shortly afterwards, his nephrologist (kidney specialist) did a blood test. "That same evening around midnight I got a call from an anonymous number. I didn't answer because I didn't know who it was. The next day it turned out that it was my doctor, who wanted to see me as soon as possible. She told me that my kidney function was so bad that I had to start dialysis immediately and that I needed a new kidney in the short term."

"I didn't dare to ask my girlfriend to marry me until I knew the transplant had been successful."

Tugrul had to go to the hospital for emergency surgery. There he was given a abdominal catheter to which the dialysis machine had to be connected. Four times a day, two liters of fluid flowed into his abdominal cavity via this catheter, which filtered the waste products from the blood in his peritoneum.

A few hours later, that fluid – including all the waste products – was removed from his abdominal cavity via the same catheter, to start the process again. In this way, part of his kidney function was taken over. Later, this 'only' had to be done at night, until the transplant could take place.

Tugrul was lucky that a donor was found quickly: his mother. But because of waiting lists, it would ultimately take another ten months before the hospital had time to perform the transplant. Ten long months. "People think that dialysis is an ideal solution for kidney failure, but during that period I thought: I never want to experience this again."

Early relationship"I had two liters of extra fluid in my abdomen every day, which pushed against my lungs, making it harder to breathe. I felt nauseous and was so tired that sometimes I couldn't lift my head. I was lucky that I could do dialysis at home and didn't have to go to the hospital, but that meant I could never be away from home for a night, because I had the dialysis machine at home."

"That affected my relationship, which was still relatively new. I didn't feel good enough for her, what would a young woman like her do with a sick man? It also felt like our lives were at a standstill. For example, I didn't dare to ask her to marry me until I knew that the transplant had been successful."

Maximum 15 percent kidney functionAnd no matter how tough the treatment, dialysis can take over a maximum of 15 percent of a person's kidney function. As a result , one in six dialysis patients still dies of kidney failure - in the 45 to 65 age group, half die within five years.

Tugrul and his family went looking for a hospital with shorter waiting lists and found one in his native Turkey. "We would have had to pay 10,000 euros there, the operation there was not covered by my Dutch health insurance. But of course we were willing to pay that. It was that my doctors in the Netherlands advised against it: it is best to have a hospital nearby, for all aftercare. Suppose something were to go wrong, for example I were to reject the kidney, then I would be able to see a Dutch doctor more quickly so that he could intervene. In the Netherlands I could not find a hospital that wanted to provide aftercare for an operation in Turkey."

Long waiting listTugrul decided to wait until there was room in the Netherlands. In the meantime, he felt worse and worse. "I called the hospital to ask if they had at least an indication of when I could be operated on. Then they said: it could be July, but also September. It became August. A week in advance they called that there would be room, so my mother came over from England in a hurry, where she stayed when I moved to Delft. I did feel guilty about that: suddenly she had to rearrange her schedule to come and help me."

But of course she did. In a kind of double operation, her kidney was removed, to be transplanted immediately afterwards into Tugrul. The operations went well. His mother recovered quickly, and Tugrul also slowly started to feel better.

"If my kidney lasts 15 years, I have another 12 to go. That sounds like a lot, but for this kind of research it isn't."

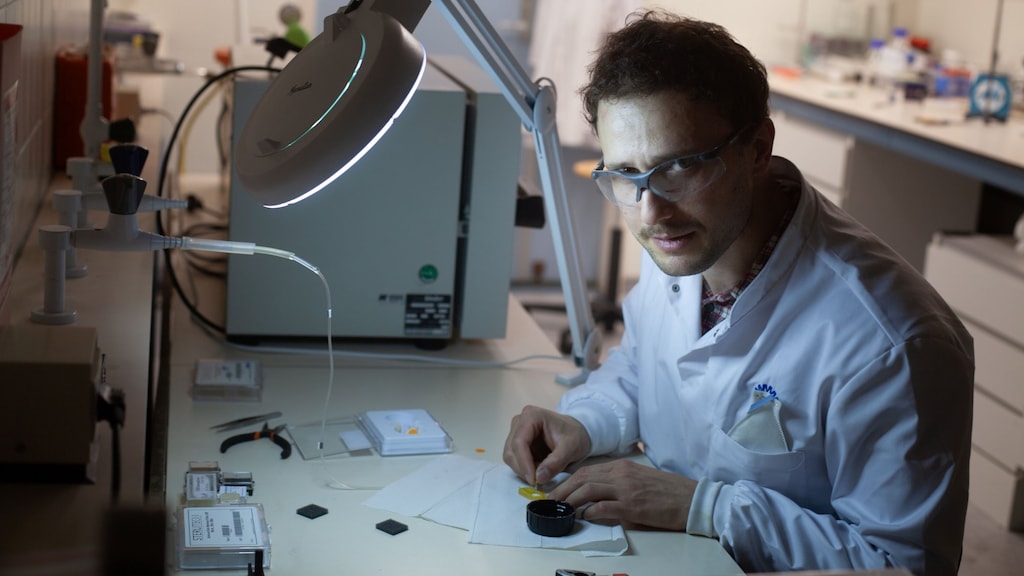

During the dialysis, Tugrul, who had since obtained his PhD at TU Delft, had decided that he would do everything he could to develop an artificial kidney. He hoped that this would make dialysis redundant and allow people with kidney disease to lead a normal life.

The day after his surgery, his contract for the research he is doing at the UMC Utrecht officially started. He took two weeks to recover, after which he started his so-called postdoc. A race against the clock, it is.

Preventing dialysis in the future"A kidney from a living donor lasts an average of 15 to 20 years. If mine gives up, I'll have to go back on dialysis until a new donor is found, and that will be a lot more complicated because it's not in my family. My mother can't give me her one functioning kidney as well."

"I want to do everything I can to prevent dialysis, for me and for all those other kidney patients. That would also be a solution for the high healthcare costs: kidney dialysis costs between 80,000 and 120,000 euros per patient per year. It would put an end to the shortage of donor kidneys. And to the uncertainty of all those kidney patients. For example, I am now 30. I sometimes talk to my girlfriend about children. But can I offer them a father? If so, what kind of father is that? One who is always sick, or one who can really be there for his children?"

What complicates the development of the artificial kidney is the complicated function of a kidney: how does an artificial kidney recognize which substances are waste products, and above what concentration in the blood you have too much of something?

Marathon session mountain climbingTo reinforce his goal, Tugrul has set off on a marathon mountaineering session this week. Between May 15 and October 15 of this year, he wants to climb 41 mountains of at least 4,000 meters high: half of all mountain peaks of that height in the Alps. The Climb Against Time , he calls it: the climb against time. Both because of the relatively short time he has set aside for this, and because of the goal: to develop an artificial kidney within the time that his kidney is still functioning.

He hopes to raise money with it so he can hire more people for his research, which he is currently doing largely on his own. "But if I can only create awareness of the fact that dialysis is not a real solution for kidney failure, then I'll be happy."

Tugrul is taking unpaid leave for this, although he will continue to work as much as possible on the ultimate goal: the artificial kidney between climbs. "I'm looking forward to it, but I'm also nervous," he says a few weeks before he starts. "It's not without danger: the weather can change, I can make a mistake. But I'm in good shape and I've had check-ups to make sure my health can handle it."

Climbing togetherA group of people climbs with him, in varying compositions. Others draw attention to the good cause in other ways: for example by cycling or running. "It's great to see how many people want to commit themselves to the same cause. I have climbing partners from the United Kingdom, where I grew up, but also from the Netherlands. They are all people I know, which is necessary because you depend on each other: if you are tied together by a rope, a misstep by one person is also a great risk for the other. These are all people I trust - and they trust me too."

Once the climb is over, Tugrul will return to the Netherlands as soon as possible to continue his research. "If we assume that my kidney will last 15 years, then I still have 12 to go. That sounds like a lot, but for this kind of research it is not. As soon as the kidney is there, we have to test it in the laboratory, in people, and only then can it be marketed. It is a matter of patience. But with enough money and commitment it must succeed, and then no one will need dialysis anymore. I am convinced of that."

Every Sunday we publish an interview in text and photos of someone who does or has experienced something special. This can be a drastic event that the person deals with admirably. The Sunday interviews have in common that the story has a great influence on the life of the interviewee.

Are you or do you know someone who would be suitable for a Sunday interview? Let us know via this email address: [email protected]

Read the previous Sunday interviews here .

RTL Nieuws

%3Aformat(jpeg)%3Abackground_color(fff)%2Fhttps%253A%252F%252Fwww.metronieuws.nl%252Fwp-content%252Fuploads%252F2025%252F05%252FANP-371945595.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpeg)%3Abackground_color(fff)%2Fhttps%253A%252F%252Fwww.metronieuws.nl%252Fwp-content%252Fuploads%252F2025%252F05%252FANP-527895658.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpeg)%3Abackground_color(fff)%2Fhttps%253A%252F%252Fwww.metronieuws.nl%252Fwp-content%252Fuploads%252F2025%252F05%252Femojisprout-emojisprout-com-K10cyANtA70-unsplash.jpg&w=3840&q=100)